Why Kemp hopes to capitalize on an industry mag’s biz ranking

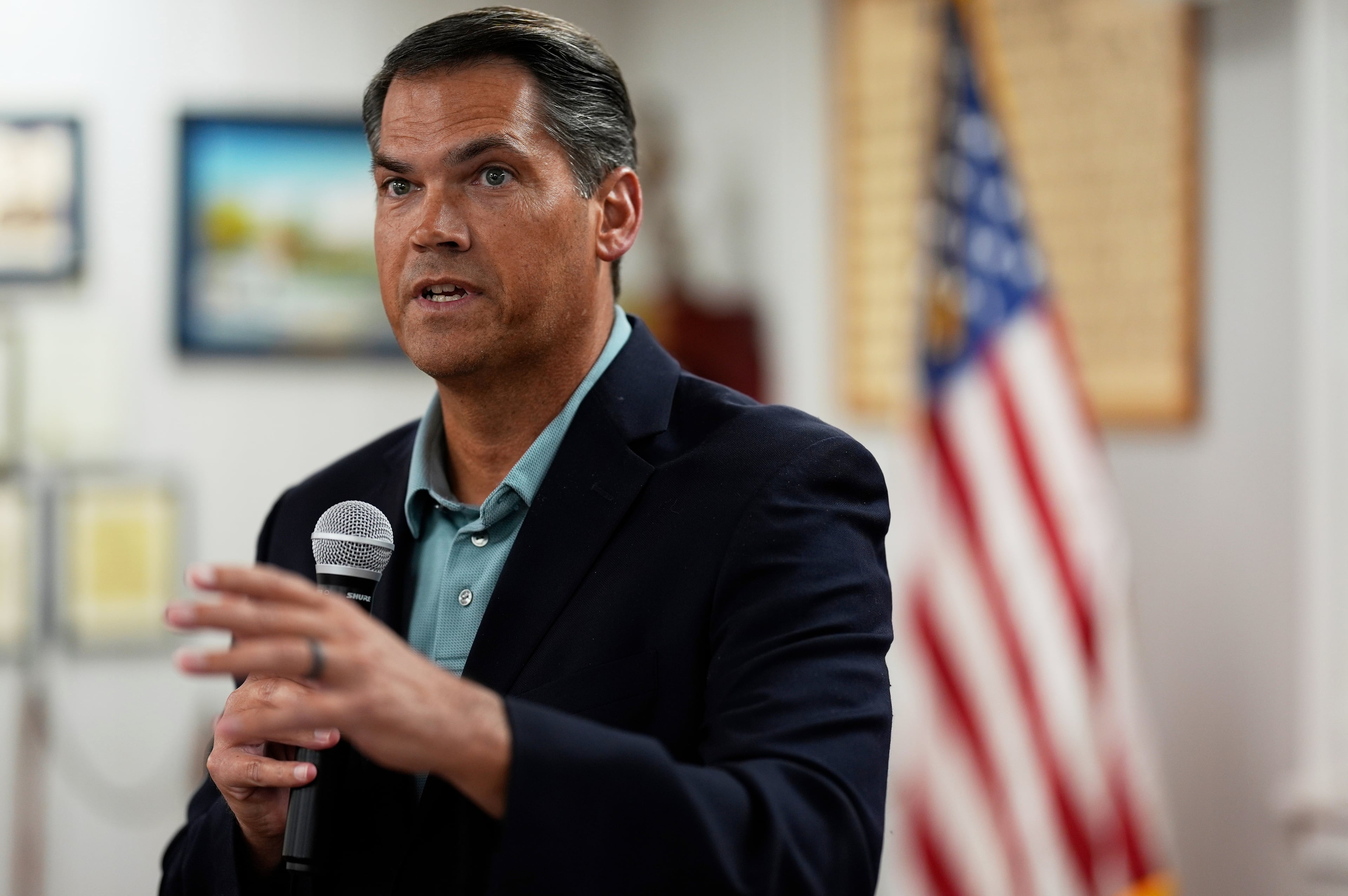

At a reception at the Governor’s Mansion, Gov. Brian Kemp stood shoulder to shoulder with his predecessor to celebrate “a decade of business excellence.”

The reason for the Tuesday gala on the steps of the Buckhead estate? Area Development Magazine, an industry publication, named Georgia the top state for business a 10th consecutive year.

Most Georgians have never heard of the magazine, which targets development experts with detailed coverage of tax incentives and site selection tips, or another niche publication that has also regularly ranked the state atop its kudos list.

But Kemp and Nathan Deal each deployed the rankings on the campaign trail as governor despite howls from Democrats who criticized the plaudits as meaningless. And Kemp plans to capitalize on the latest ranking as he increasingly hits the road to sell Georgia to corporate leaders and policymakers.

In the past few weeks, he wrapped up a trip to New York where he accepted an award honoring Georgia’s growing economic bond with South Korea. And he followed with a trip to Austin for the Texas Tribune Festival, where he promoted the state’s business climate during a political forum.

Kemp is freer to travel beyond Georgia with a rematch win over Democrat Stacey Abrams behind him — and the possibility of a run for higher office ahead. He’s often used his visits to press both a political and economic message as he navigates a rising GOP profile and his job as Georgia’s chief cheerleader.

During an overnight visit to Milwaukee in August, for instance, he urged Republicans to move beyond Donald Trump’s fixation with his 2020 defeat and called the former president the “loser” for skipping the first GOP debate.

But he also touted Georgia’s growing green industry, which has drawn a string of multibillion-dollar electric-vehicle and clean energy projects that promise tens of thousands of new jobs.

Kemp’s critics say the governor’s selective use of the glowing accolades masks the state’s other pressing economic problems, such as an ongoing struggle to provide health care to needy residents and undo stubborn economic inequality.

State Sen. Elena Parent, one of the top Democrats in the chamber, said her party always applauds the bipartisan goal of economic development successes.

“At the same time, we are focused on other initiatives that will help grow our economy and where our state is lacking,” she said, “such as ensuring every child can read, investing in our state’s education system at all levels and ending the Republicans’ refusal to expand Medicaid.”

Boosting his profile

The travel helps Kemp expand more than his network. The governor often adds fundraisers to his visits, and he is still leveraging a leadership committee that allows him to collect unlimited contributions and then use the cash to directly support his political agenda.

This year alone, Kemp has also taken three overseas trips: He participated in the elite Davos conference in Switzerland and in May completed a trade mission to Israel. In June, he embarked on a two-stop trip to the nation of Georgia and the Paris Air Show in France.

Each visit carries a different selling point. In Israel, state officials emphasized Georgia’s tech industry and network of Israeli companies. To European leaders on edge after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kemp focused on the reliability of Georgia’s power grid with the expansion of Plant Vogtle’s nuclear complex.

“I just came back from Europe last week, and one of the main drivers for European companies is investing where the energy market is stable,” said Pat Wilson, the state’s economic development commissioner. He added that it puts Georgia at a “tremendous advantage” for companies aiming to meet carbon-neutral goals.

The governor has chalked up some of his visits to pent-up demand. He canceled or postponed much of his travel during the global pandemic in 2020, including his long-promised trip to Israel, which he said during his campaign for governor would be one of his first international stops.

And he could ill afford to spend much time out of the state during his 2022 reelection campaign, when he faced challenges from a Trump-backed rival in the GOP primary and then a rematch against Abrams, whom he narrowly defeated in his first run for governor.

But it also coincides with Kemp’s efforts to boost his profile beyond Georgia and, possibly, set the stage to run for federal office after his term ends in 2026. While he could challenge first-term Democratic U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff, his allies also want to position him for a possible White House bid in 2028.

Sometimes, it makes for an uneasy political dynamic. In a gilded ballroom inside Manhattan’s famed Plaza Hotel last month, the Korean Society honored Georgia’s economic development arm for growing economic ties between the Peach State and South Korea.

At the black-tie event, Hyundai North America’s top leader, Jose Munoz, hailed Kemp as “a man who has done more for Korean business in the U.S. than perhaps anyone else.” Outside, demonstrators loudly chanted their opposition to the $90 million Atlanta public safety training center that Kemp backs.

Kemp has shrugged off the blowback. Almost as soon as he announced the magazine ranking, economists and others immediately mocked what his office had billed as a “major economic announcement.” The governor carved out a line in his speech for critics.

“Since we first received the No. 1 business ranking 10 years ago, over 343,650 new jobs have come to Georgia,” he said. “And those are just the projects that the state played a role in.”