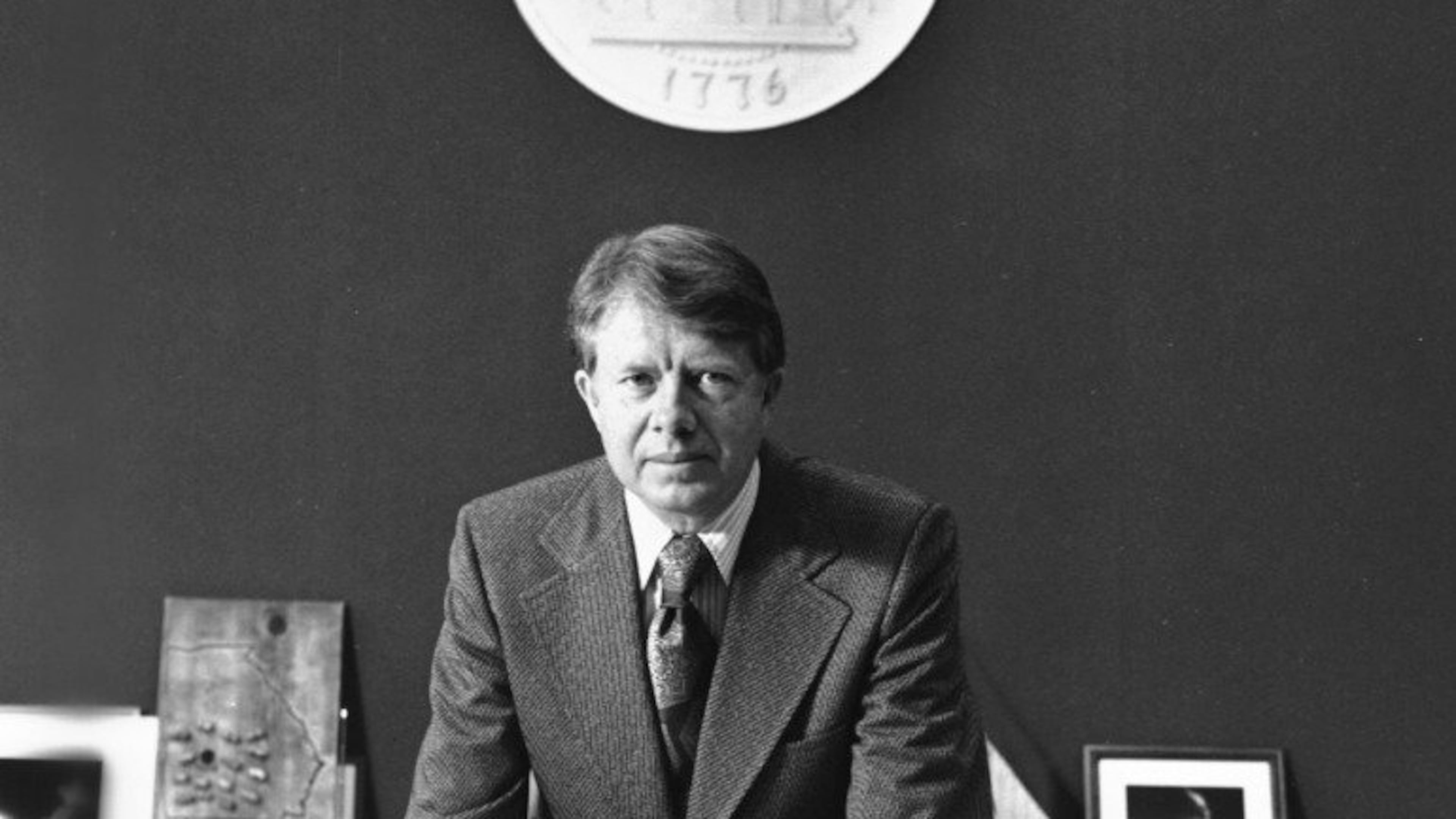

Jimmy Carter’s term as Georgia governor was marked a success

In a single term as governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter propelled the state into a new era.

The acronyms for state offices that still populate news stories about Georgia government – DOT, DNR – are lasting reminders of the massive reorganization that was a hallmark of his administration.

But his legacy had already been largely determined by the time he sat down from giving his inauguration speech on Jan. 12, 1971.

“I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. Our people have already made this major and difficult decision,” Carter said as he stood in front of the Capitol, pronouncing the end of a painful era with an engineer’s perfunctory certainty.

The shock value of those words would fade quickly as Georgia raced ahead over the following years. But on that stage, that day, they came as a thunderclap.

The former governor, Lester Maddox, had sold his Atlanta restaurant rather than serve black customers. George Wallace, running in the presidential primaries on a defiantly segregationist platform, carried the state in the 1968 election. And the rural populist campaign Carter ran for governor against “Cufflinks Carl” Sanders reminded many observers of the Alabama governor’s anti-establishment style, with whiffs of appeals to segregationists.

Although his family was considered relatively liberal on such matters, Carter had straddled the race issue in his campaign, remarking to a reporter that he had “no trouble pitching for Wallace votes and Black votes at the same time.”

Dick Pettys, who was a young reporter for the Associated Press, remembers the impact of the governor’s inauguration speech, which would land Carter on the cover of Time magazine as one of the “New South” governors making a departure from the segregated past.

“That just blew everybody away, because they thought he was a Democrat just like all the other Democrats,” Pettys recalled.

Carter made the bold statement at the suggestion of David Rabhan, a retired Air Force colonel and businessman who piloted his campaign plane. Rabhan would later spend a decade in an Iranian prison on an espionage charge, with Carter lobbying for his release post-presidency. But Carter’s racial views had already undergone a complex evolution.

Carter’s first political race, for state Senate in 1962, came about because of an opening that was an indirect result of the landmark Baker v. Carr U.S. Supreme Court case affirming the “one man, one vote” principle.

In his book “Turning Point: A Candidate, a State and a Nation Come of Age,” Carter described how he came to see his own aspirations, returning to his home state from the Navy, at the same time that African Americans in Georgia began demanding their share in the political system.

His Navy career as an officer working on Adm. Hyman Rickover’s nuclear submarine project was shortened by the the death of his father and the demands of his family’s peanut warehouse business.

When he returned to Plains, Carter brought ideas about modernizing the state, as well as a methodical, tireless style.

This quality was in evidence after Carter finished third in the Democratic primary in his first bid for governor in 1966. He quickly set about keeping his political network alive after his loss, traveling the state in preparation for the 1970 race, defeating Sanders, the early favorite, by nearly 20 points, and Republican Hal Suit by a similar margin.

His major campaign pledge was to bring order to the tangle of agencies, boards and commissions in state government. He made good with a reorganization bill which passed the House by one vote. His work still forms the basic organization plan of much of state government.

Carter brought new faces into state government, including banker Bert Lance, who was given the most politically sensitive job, replacing the powerful state highway director, Jim Gillis, whom Carter had promised to fire during the campaign. Lance, who would become director of the federal Office of Management and Budget under President Carter, oversaw the conversion of the Highway Department into the Department of Transportation and helped Carter in his dealings with legislators — no easy job in itself.

Lance recalled in his autobiography one of those dealings when a senator dropped by and presumed to tell the new governor how to get along with the state Senate.

“I was watching Carter’s forehead. He has a vein that throbs when he’s getting mad, and that thing was going, Pow! Pow!”

Carter is recognized as the state’s first environmentalist governor, highlighted by his action in stopping a planned dam on the Flint River at what is now Sprewell Bluff State Park west of Thomaston.

Later, as president, he would push and sign the documents that created the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area in metro Atlanta, and other bills that set aside millions of acres in Alaska and the lower 48 states. During the 1979 energy crisis, he had solar panels installed on the roof of the White House. President Ronald Reagan had them dismantled in 1986.

While governor, he appointed more Blacks and women to positions in state government than any of his predecessors, enforced zero-based budgeting in the newly created departments, and won passage of a modest education plan. But by the end of his term, Carter’s relationship with the General Assembly had frayed.

“He was fixated on doing things on time, and that irritated people to no end,” Pettys recalled.

In those days, state law didn’t allow governors to run for a consecutive term. After four years of bruising political battles, it’s far from certain he could have been reelected. But more than a year before he left office, Carter had already announced he was running for president, and set his sights on broader horizons.

More Stories

The Latest