Hosea Helps, a friend of hungry, homeless, finds itself a real home

When Hosea Williams died on Nov. 16, 2000, just days before his annual Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless Thanksgiving Dinner, he had $286 in the bank.

That was not altogether unusual. For 30 years up until that point, Hosea Feed the Hungry and Homeless operated by the seat of its pants, scrambling up until the last moment to find food, clothing and a place to feed hungry and poor people. Then doing it all over again.

Those days are gone, as Hosea Helps, as it is now called, has become one of Atlanta’s leading charities, feeding, clothing, and offering social services to more than 51,000 people annually. Further evidence of the organization’s rise came last month when it held the grand opening of its new facility in Perkerson Park, which it raised $1.8 million to purchase and repurpose.

When they cut the ribbon, it marked the first time that Hosea Helps has owned its own building.

“This is our time to transform. Like a butterfly coming out of a cocoon,” said Hosea Helps’ COO Afemo Omilami. “Never again shall we be homeless.”

Just before the grand opening, the sprawling building was teeming with workers as they prepared for this year’s Thanksgiving dinner, which will be held this Friday at 11 a.m. in the Blue Lot of the Georgia World Congress Center.

Elisabeth Omilami, the daughter of Hosea Williams and the face of the organization as the CEO, walked around the facility greeting all of the workers and showing off the new digs.

The pandemic has changed the way the organization operates, but the volume of work has not decreased, she said.

“We never stopped serving. We are not a food pantry, but we feed more people than most food banks in the region,” Elisabeth Omilami, 68, said. “And we know how to develop and mobilize volunteers.”

Because of COVID-19, this year’s dinner will be a drive-thru affair. Hopeton Gordon, one of 21 full-time workers, who had been with Hosea Helps for more than 30 years as a warehouse manager, packed boxes with enough food to feed a family of four for two weeks.

That wasn’t including the whole turkeys that would come later.

They are expected to feed more than 2,000 people between Thanksgiving and Christmas. Both drive-thru dinners will happen a week before the holidays to put less pressure on parents and give them a chance to prepare and serve a hot meal on the holiday.

“Hosea’s Feed the Hungry and Homeless is as synonymous with Atlanta as the Braves and Falcons thanks to the unyielding commitment of Elisabeth Omilami,” said Rolundus R. Rice, whose new book, “Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest,” will be released in January. “It is clear that she inherited her father’s humanitarian zeal for the forlorn and forgotten.”

The Omilamis walk through the facility almost hand-in-hand, a doting couple and a product of 44 years of marriage.

A family’s legacy

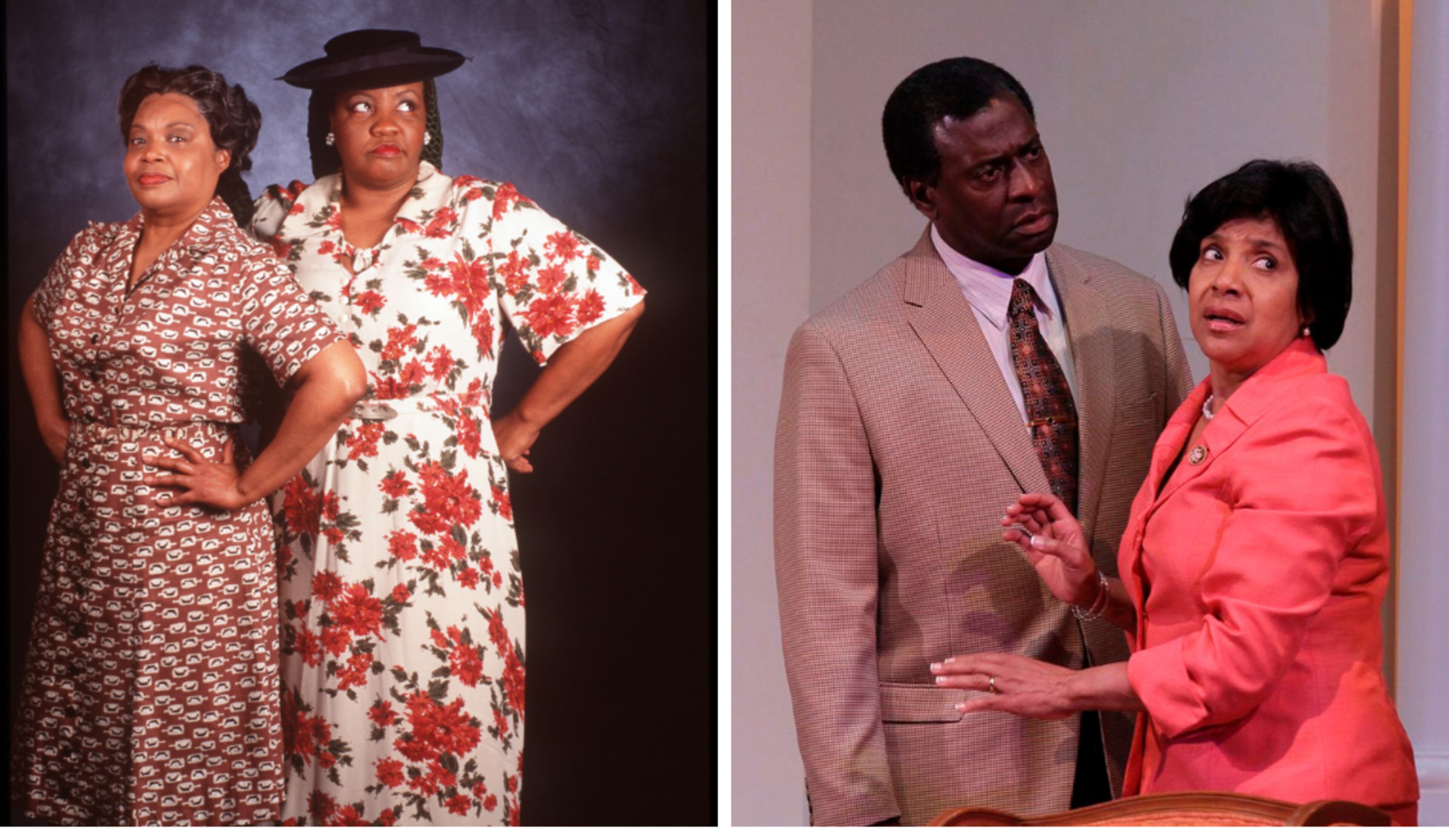

They would be familiar faces even if you never met them. Both are solid and dependable character actors, each with a string of movie, television and theater credits ranging from the groundbreaking “Sankofa,” to “Boycott.” Afemo, 70, is set to appear in the upcoming Emmett Till biopic and Elisabeth Omilami is venturing toward reality television with a role, playing herself, in her niece Porsha Williams’ new reality show.

He calls her “Mrs. O.”

She calls him “Mr. O.”

When Elisabeth Omilami arrives a few minutes late for a photo shoot, “Mr. O” rubs her shoulder and tells her to “breathe.”

It is a subtle reminder, but apt, as they both are always on the run.

They are constantly on the phone raising money or negotiating with vendors to get food and supplies. They get about 200 calls a week for rent and utility assistance, and they truck food to disaster zones and pay for hotel rooms for the displaced who find themselves in Atlanta. Like the victims of Hurricane Ida.

The aura of Hosea Williams is all over the new facility. There are photos and quotes from him in nearly every room. In the main foyer, an entire wall is a giant, illustrated timeline tracing Williams’ colorful life.

An Army veteran born to blind parents in Attapulgus, in southeast Georgia near the Florida border, Williams graduated from Morris Brown College but didn’t join the SCLC and start working with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. until around 1964.

He quickly made a mark and became one of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s most trusted leaders. On March 7, 1965, Bloody Sunday, it was Williams who stood side by side with John Lewis as they attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the march for voting rights.

In November 1970, two years after King was assassinated, Williams was walking down Auburn Avenue, where he spotted a homeless man eating out of the trash can.

“He was furious,” Elisabeth Omilami remembers.

A few days later, he held his first Hosea Feeds the Hungry and Homeless Thanksgiving Dinner at Wheat Street Baptist Church.

“My mother (Juanita Williams) cooked the soup and I tried to cook the cornbread,” Elisabeth Omilami said. “But we pulled it off. We came out of the civil rights movement. That is where we get our direct-action ideology.”

Over the years, the dinner, which started out as a way to feed homeless men, grew as poor families started to arrive looking for a hot meal on the holidays.

Elisabeth Omilami remembers a gathering in the days after Williams died in 2000, when someone asked, “Who is gonna help us now?”

Hosea L. Williams II, who had been the natural heir to take over, died two years earlier.

Elisabeth and Afemo Omilami had their bags packed and were preparing to move to Los Angeles to further pursue their promising acting careers.

“But we were the family members who knew how to run these big dinners,” Elisabeth Omilami said. “Our other siblings had their own lives. So, when they looked around, they saw us. They saw us in the back of trucks counting cans.”

Afemo Omilami said that after Hosea Williams II died, Hosea Williams started to subtly groom Elisabeth Omilami to take over.

“Hosea was really hard on Elisabeth. Testing her to see if she could handle this. He was always tougher on her, making her ready,” said Afemo Omilami, who was in Africa on a mission trip when Williams died. “Our hearts were already turning. It was a hard decision that almost destroyed the family and took a toll on our marriage and careers. But how would we feel if we walked away from this?”

Expanding to fill needs

They inherited a shoestring operation and quickly figured out that it needed to be a business to survive. They were buoyed by a $240,000 grant from the Arthur Blank Foundation to help plan logistics and to establish a fundraising apparatus that would support a capital campaign.

“Sixty percent of our donations come from individuals, but that is not sustainable,” Elisabeth Omilami said. “We had to do something different.”

In 2005, they held their first dinner on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and have since expanded to Easter. That same year, they also changed their name to Hosea Helps, to better emphasize the organization’s move to offer a wider variety of social services throughout the year. That was also the first year that the couple even started taking a salary.

“We had a vision that we were gonna be a one-stop-shop for human services, where Black people can see Black people helping them,” Elisabeth Omilami said. “Food is just a portal into the family. If a family is hungry or living in a car, it is hard to talk to them about getting a job or mental health.”

Added Afemo Omilami: “We grew because people said this is what we need.”

But in 2017, they were displaced by the Beltline when the warehouse they were renting on Donnelly Avenue was sold. They spent several years renting warehouses across the city.

“We were homeless ourselves,” Elisabeth Omilami said. “But if we hadn’t gotten kicked out, we would still be in that raggedy building.”

The new building is anything but. From a small lounge, a coffee maker fills the lobby with a strong aroma. Afemo Omilami gets a cup and the couple walks through the building, past the Hosea Williams mural, and heads to the sprawling warehouse sitting on more than 2 acres.

Mountains of canned goods are stacked on pallets against the walls.

“This is our dream,” Afemo Omilami said. “It gets us high because we know what this is gonna do for families. Hosea Williams gave us a gift and we are sharing it.”

Editor’s Note: Hopeton Gordon, the Hosea Helps veteran of more than 30 years, died before the publication of this article. This year’s Thanksgiving dinner will be dedicated to his memory.