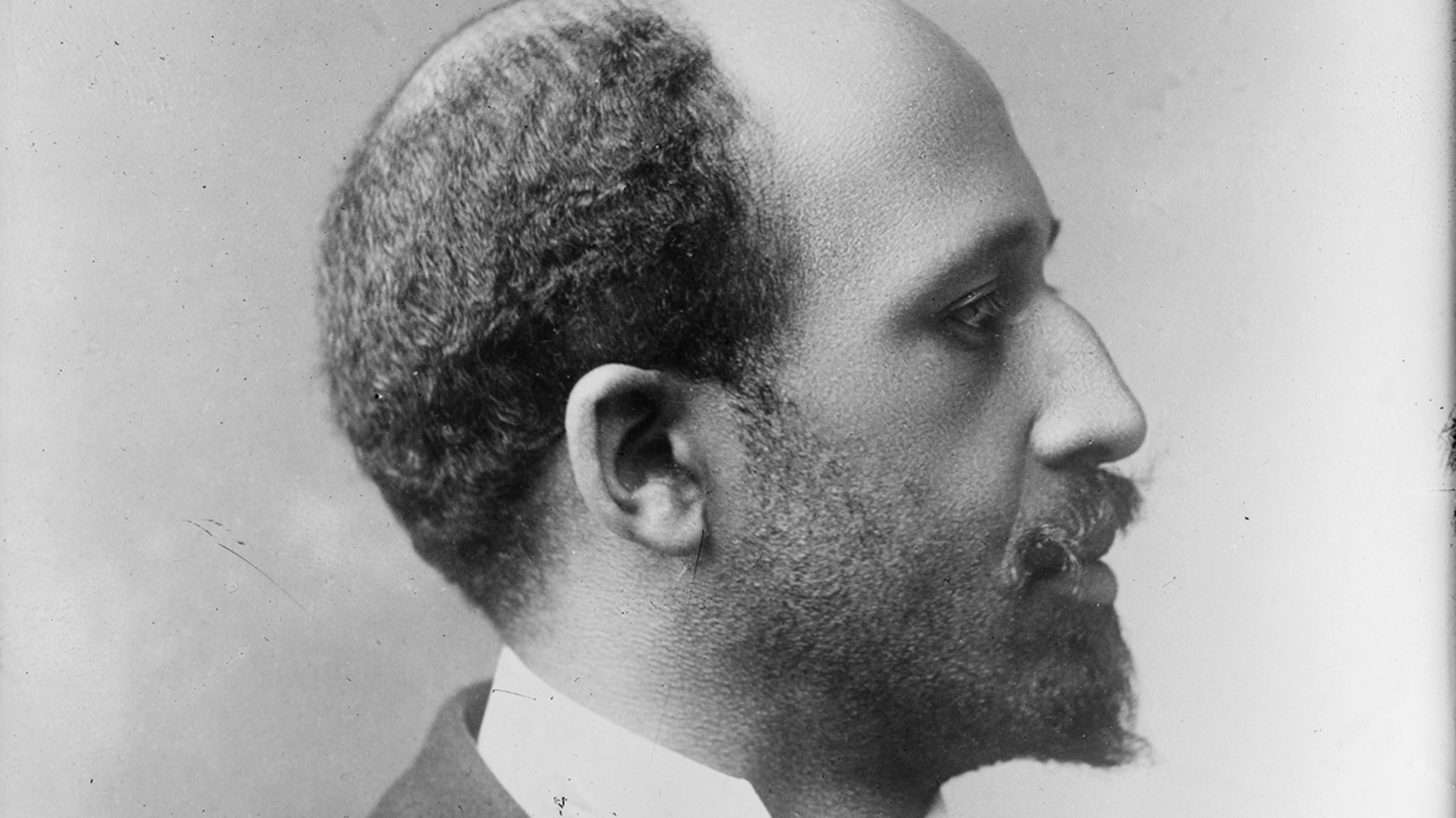

W.E.B. Du Bois historical marker placed on Morris Brown campus

In 1906, from a window in his tiny office on the second floor of what was called Stone Hall, Atlanta University professor W.E.B. Du Bois watched Atlanta burn.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre shocked the world, redefined the city, and ultimately changed Du Bois, who after writing his powerful poem, “The Litany of Atlanta,” in the terror’s wake, left the city to become one of the founders of the NAACP.

On Wednesday, more than a century later, from that same window, the view of a thriving city with Black leadership and an expanding Black political, financial, and cultural influence is clearer.

The Georgia Historical Society, The Rich’s Foundation, and Morris Brown College dedicated a historic marker in honor of Du Bois, who was one of America’s leading historical scholars with deep Atlanta connections.

“He wasn’t just a great African American,” said W. Todd Groce, president and CEO of the Georgia Historical Society. “He was a great American.”

On the lawn of what is now called Fountain Hall, the black marker noting Du Bois’ work as a scholar and activist was unveiled in front of a host of Morris Brown alumni and his great-grandson.

The marker is the first to recognize Du Bois in the South and part of the Georgia Historical Society’s continued efforts to build a Georgia Civil Rights Trail, highlighting Black achievement across the state.

Between 1953 and 1998, the state of Georgia ran the marker program. They put up roughly 2,000 markers over that period and about 90% of them recognized events related to the Confederacy and the Civil War.

Once the program became privatized, Groce said the organization tried to correct the record.

“If we are going to know who we are as a people, we have to know everything about our past,” Groce said. “The good, bad, and the ugly.”

The Du Bois marker, said Elyse Butler, the Georgia Historical Society’s manager of programs and special projects, is part of a five-marker series funded by The Rich’s Foundation to put up key Civil Rights memorials around the city as part of the Georgia Civil Rights Trail.

Another marker will go up on Oct. 29 at Booker T. Washington High School, which is celebrating its centennial as the first public high school that educated Black students in Georgia.

“We continually encourage communities to apply to expand this narrative,” Butler said.

Stephanie Y. Evans, a professor of Black women’s studies at Georgia State and a former professor at Clark Atlanta University, where she developed a course of study devoted to Du Bois, said the placing of the marker is “long overdue and right on time.”

“Du Bois’ work in the Atlanta University Center is foundational to why and how Atlanta became the cultural juggernaut that it is now,” said Evans who got her Ph.D. from the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and where Du Bois’ papers are housed. “His story is timeless and needs to be part of the formal historical record.”

Du Bois spent a lot of time in Atlanta during two teaching stints at Atlanta University 1897-1910 and 1934-1944. His office in Fountain (Stone) Hall, was once part of the AU campus, but is now part of Morris Brown.

Three years before the 1906 massacre, from that tiny office, Du Bois looked upon the growing and changing city as he wrote his seminal work, “The Souls of Black Folk.”

While watching the birth of Atlanta’s Black middle class Du Bois penned the classic line in the book, “The problem of the 20th Century is the problem of the color line.”

He wrote “Black Reconstruction” in 1935 during his second stint in Atlanta and remained an outspoken critic of Jim Crow laws.

“He taught the longest here while producing groundbreaking scholarship,” said Du Bois’ great-grandson Jeffrey Du Bois Peck. “I believe ceremonies and events like these keep history alive while people are trying to erase history.”

Wearing a three-piece suit, a gentle nod to his great-grandfather’s sartorial style, Peck was visibly moved by the honor.

“It’s extra special because we are in the South and he spent so much time on this campus,” said Peck, the CEO of the W.E.B. Du Bois Educational Foundation. “We know how things were in the South and we know how Du Bois felt about Civil Rights and equality. He promoted education among minorities.”

Du Bois was born in 1868, three years after the abolishment of slavery.

He died on Aug. 27, 1963, one day before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream Speech,” at the March on Washington.

“This dedication is so timely because so many of his lessons remain relevant and need to be taught and retaught,” Evans said.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.