Rich Homie Quan’s love for baseball never faded

It was supposed to be a routine fly ball.

Traditionally a second baseman, it was Dequantes Lamar’s first time playing outfield for the varsity baseball team at Ronald E. McNair High School. Like any good center fielder, Lamar remembered what his coaches told him: When ball meets bat, your first step is back.

Instead of taking a single shoe step in reverse, the tall, rail-thin kid took an awkward lunge backward, misreading the ball’s exit velocity. Realizing the mistake, he pivoted and ran toward the ball. Anxiously, in the dugout, his teammates and coaches watched as Lamar dove and caught the ball.

“I could tell by the look on his face from where I’m sitting, he thought he was going to drop it,” said Atlanta music executive Rich Homie Monta, who was serving as McNair’s assistant varsity baseball coach.

“He got up and he was happy as hell,” Gibson remembered.

It’s the 20-year-old memory of that young, lanky 10th-grader Monta thinks about now in light of his death. Lamar, known to the music world as Rich Homie Quan, passed away Sept. 5, at the age of 34.

Funeral services will be held 11 a.m. Tuesday at World Changers Church International in College Park. There is a waitlist for tickets to the public event.

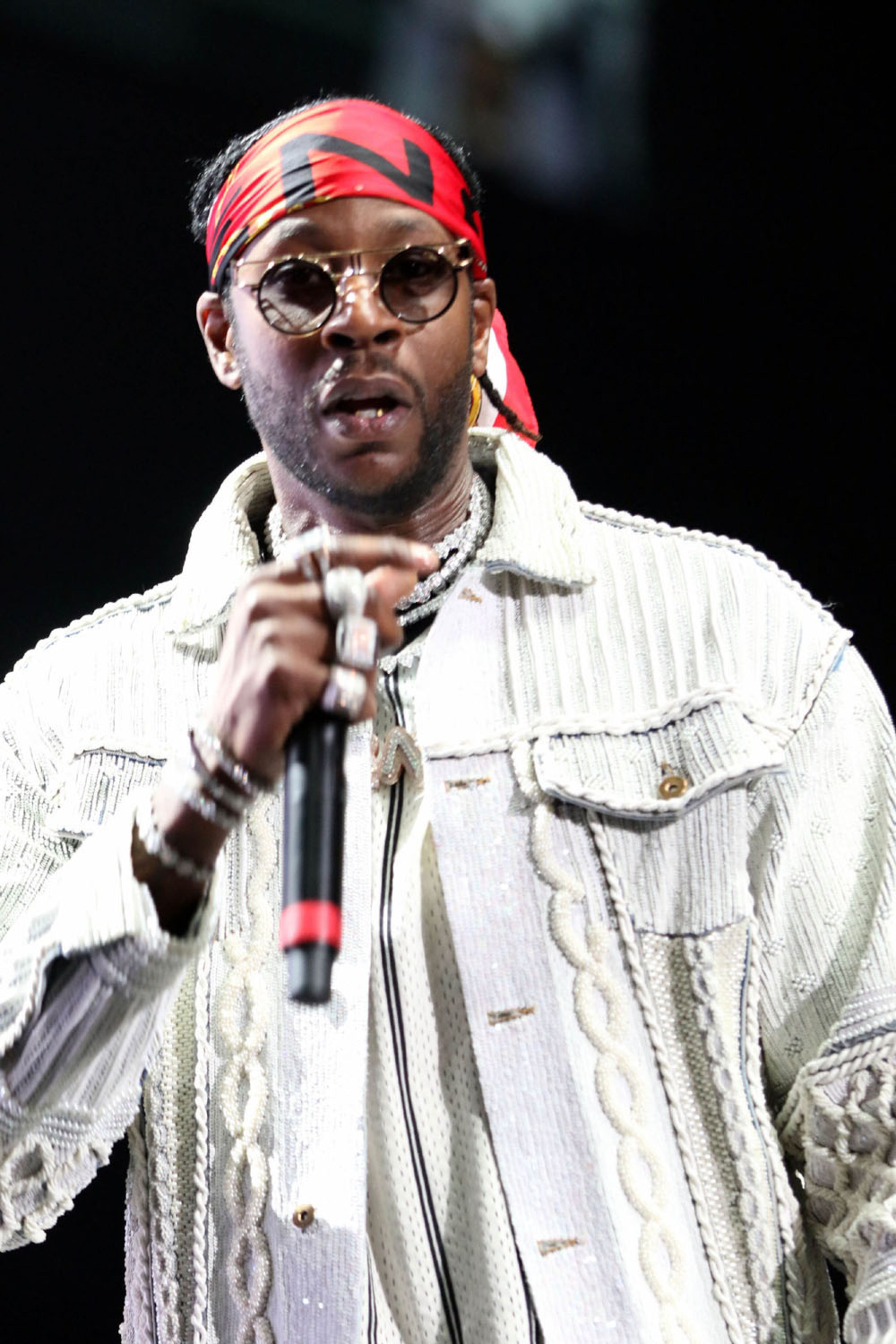

Before the world grew to know him as a melodic trap wordsmith and prominent voice of Atlanta’s 2010′s rap reign, Rich Homie Quan drew attention on the baseball field as a teenager. Despite being recruited to play in college, he eventually traded bats for bars.

Even with his music success, Rich Homie Quan’s connection to his first love continued up until his death. Whether he was talking about his beloved hometown Atlanta Braves or ways to increase Black participation in youth baseball, Quan’s heart never left the diamond.

And Monta, the first coach to take Dequantes Lamar the baseball player seriously — and who would eventually become Rich Homie Quan the rapper’s manager — was always there.

Player and coach

When Monta joined the baseball staff at McNair in 2003, it was common for Black high school coaches to scout metro area fields in Black communities for potential recruits. He remembered making a trip back then to Gresham Park, where he met Quan’s parents and saw him play. Monta insisted they send Quan to McNair where he could coach and guide the young prospect.

As a 14-year-old freshman, Quan started off playing second base and joined the junior varsity team. Monta knew Quan’s path to varsity playing time was a position switch. “He had a real nice arm. He had good technique, listened well, hit the ball. He did pretty well for me,” Monta recalled.

As promised, Coach Monta took Quan under his tutelage. They practiced fielding fly balls. They worked on Quan’s swing. It was a lot. “Everybody thought I was just so mean,” said Monta, joking about how hard he pushed Quan.

Monta played ball growing up and had dreams to play in college but injuries and being a self-described “hot head” derailed those plans. Instead, as Coach Monta, he became known for teaching by example despite being not much older than his players. He even dressed the part, in full baseball pants, cleats and cap, while leading the kids through drills.

“Quan was one of a few kids that I attached to, that I actually grew a real bond with. So that bond led me to a certain level of loyalty,” he said.

They talked about the Braves, and Quan’s favorite player, center fielder Andruw Jones. He knew the odds of making it pro as a young Black kid was were slim, but he didn’t care. “He would just always say he wanted to be different. He wanted to be that person in his family that made it to play the professional sport,” Monta said.

It’s why Monta grew worried when Quan would skip practice, often finding him in the hallway talking to girls instead. Quan, he said, would blame the team’s head coach for taking the fun out of the game but eventually Monta convinced him to come back.

After a while, coaches from colleges began asking about Quan, who earned McNair’s “Mr. Baseball” award, traditionally given to a school’s top player. He was good enough that Fort Valley State University, whom he learned was seriously considering adding a baseball program, offered Quan a scholarship.

He started skipping practice again so Monta confronted him, asking what could be more important than baseball. “He was like, ‘Man, I’ve been going to the studio. I’m going to rap,’” Monta recalled.

The coach didn’t like what his player had to say and wasn’t sold on the new path, at first. “I walked off,” he said. “It pissed me off because I wanted him to play.”

Monta also knew that he believed in Quan. He watched him constantly ask how to improve his game, whether it was building more confidence at the plate or defense. If coaches asked for 50 practice swings, he’d take 100. Monta thought if Quan could apply that same hustle to music, he might become a star. He started to believe.

“When he told me he wasn’t going to play ball no more, I was like, ‘Hey man, whatever you decide to do in life, I’m going to stick beside you,” he said.

Even playing field

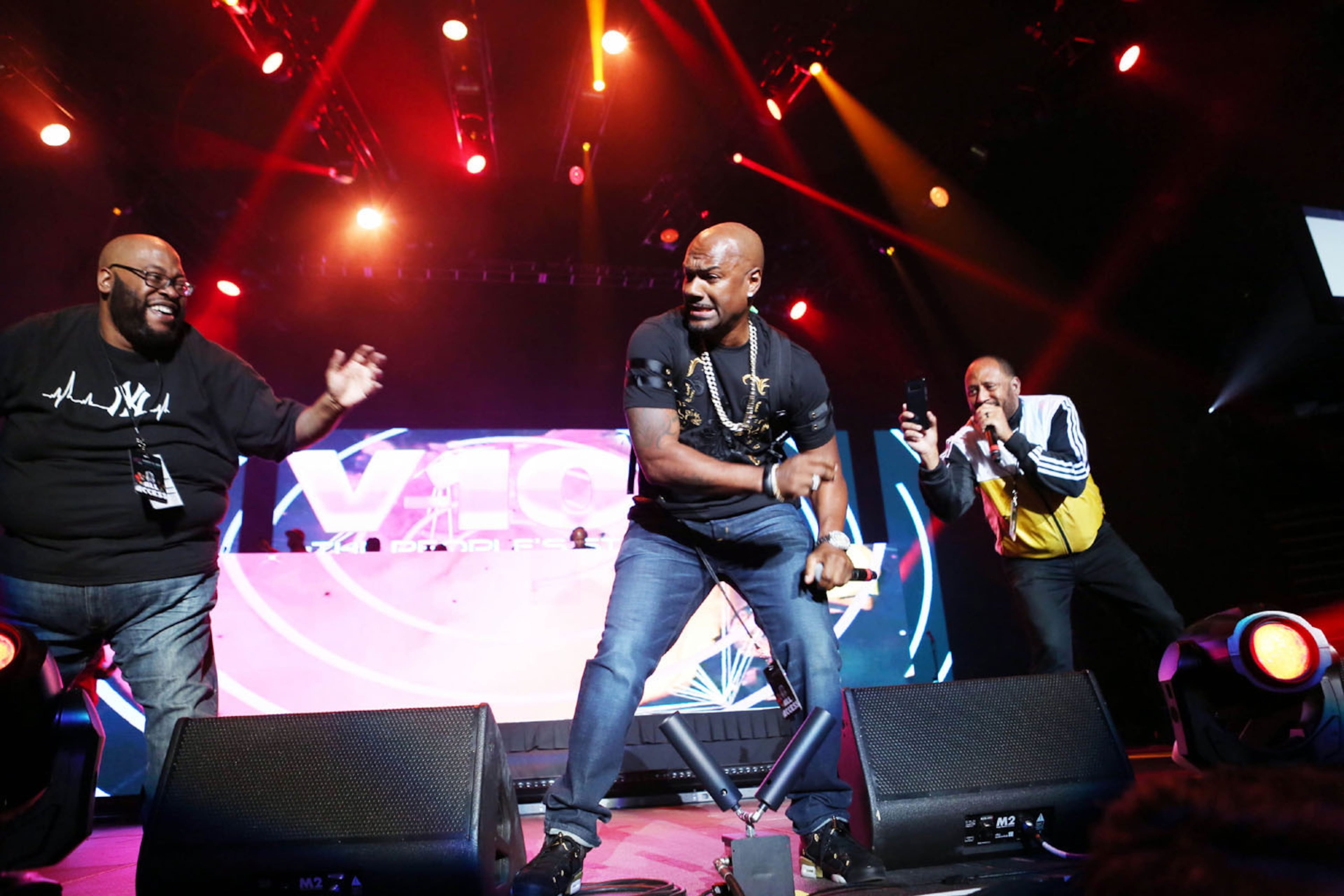

From the sandlots to stadiums, it was Quan and Monta.

The latter, a McNair drum major in the high school’s marching band, used family connections in the music industry to help Quan’s career get going. Monta had a makeshift studio set up for Quan in a pantry inside his house, where Quan spent time writing and teaching himself how to engineer.

“When you correlate the two — the baseball and the music — he was same guy,” Monta said. “He’s going to practice, practice, practice, until he gets it.”

The player-coach bond continued to build as well.

“It all comes down two people having the love of two things: We both love music and we both love baseball. So that led us to have a growing brotherhood, business partnership,” he said.

Baseball continued to show up in their lives. There was the time ESPN invited them to film a segment at a batting cage in Atlanta. The crew was surprised when Quan and Monta showed up, hands full of their own equipment.

In an interview on Vlad TV in October 2022, Quan talked about his success playing baseball but admitted he chose rap because he liked his odds of going pro in music over sports.

He wasn’t wrong. According to Major League Baseball, the percentage of Black players on opening day rosters this season was 6%. It was 6.2% last year. Only 13 of MLB’s top 100 draft prospects for 2024 were Black.

“When I would just have conversations with him about baseball, it was just like a lot of Black kids, we know how to play it, but we’re not looked at in the light of it,” Monta said.

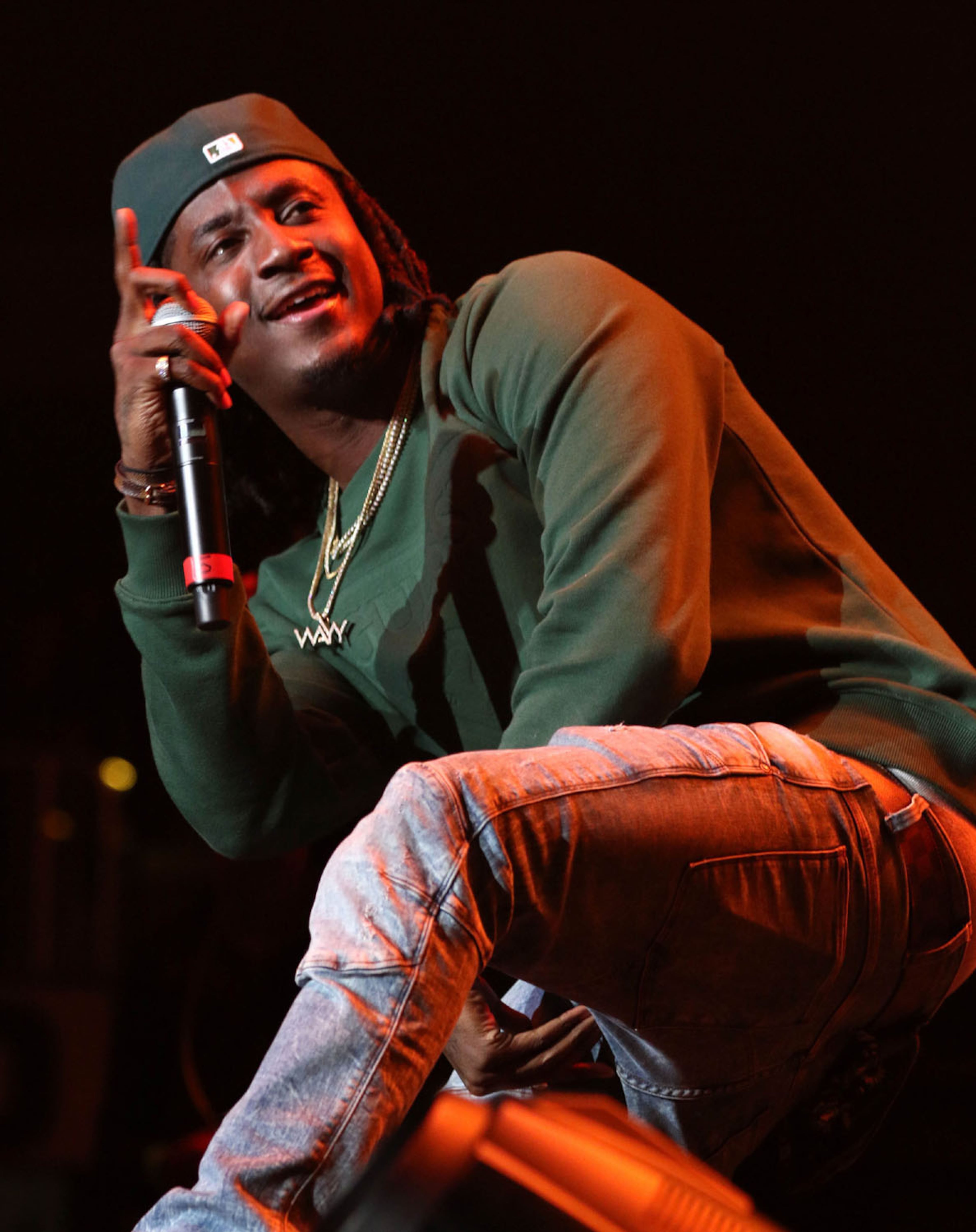

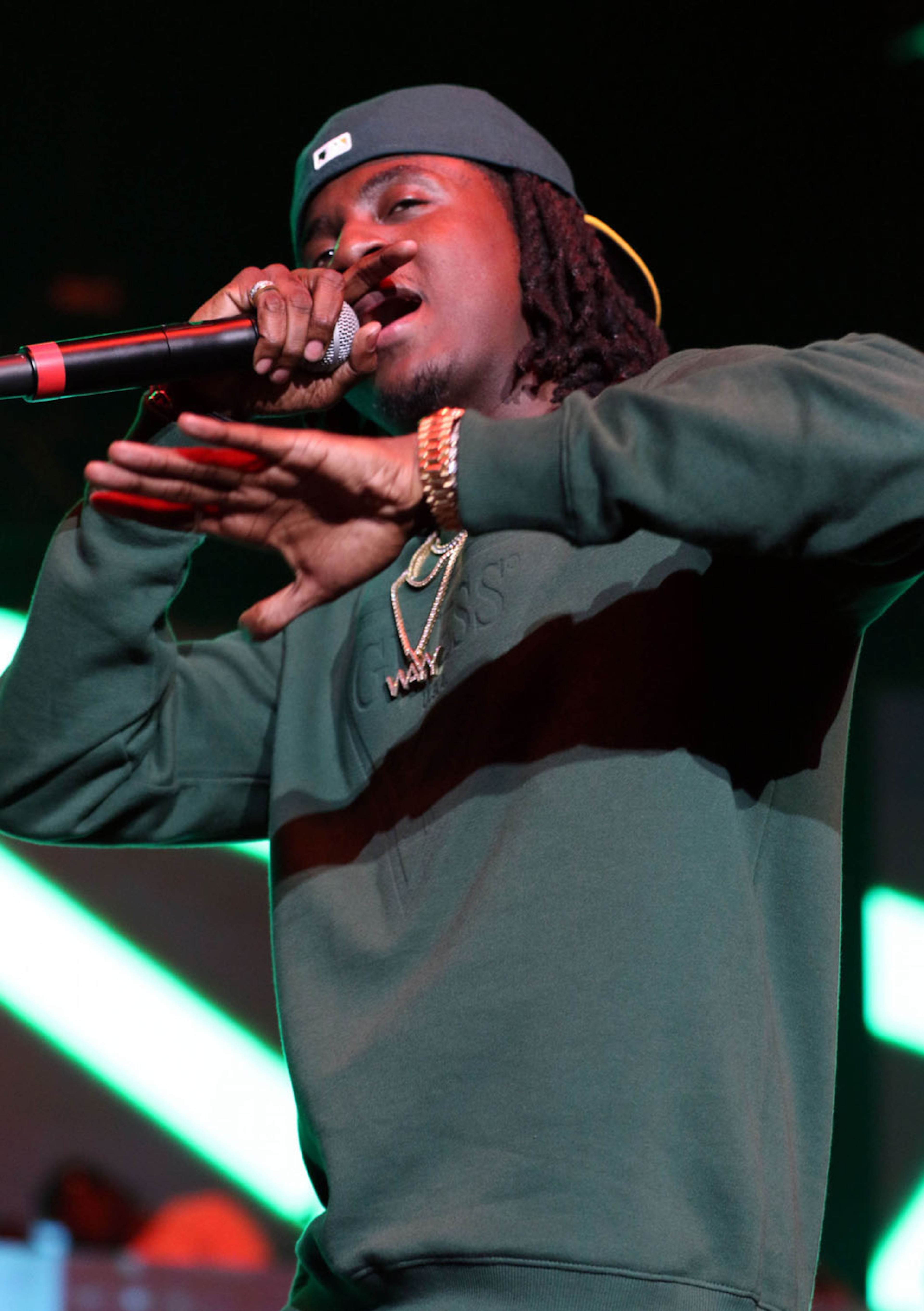

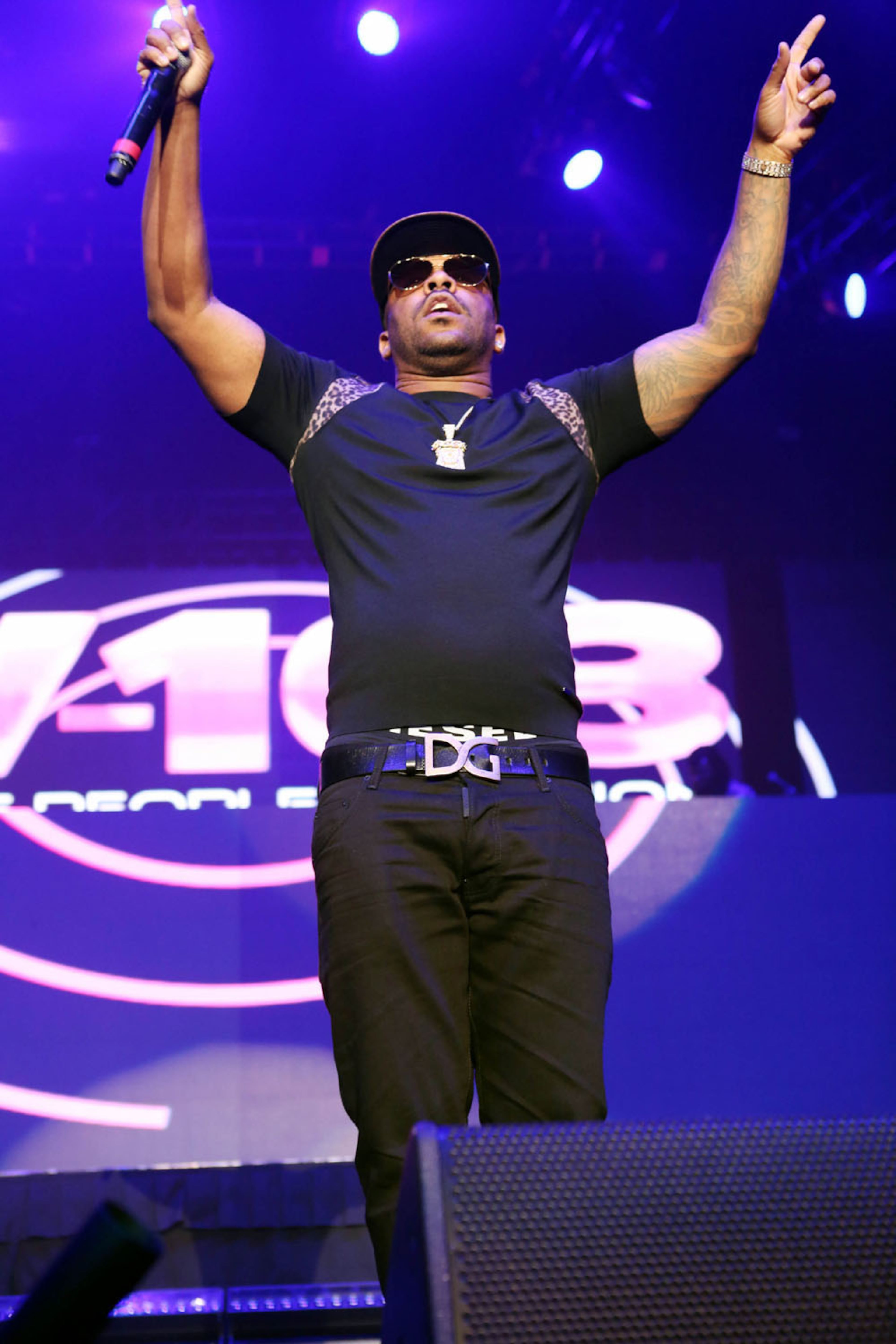

In the years before he passed, Quan used his name and influence to help the sport he loved. Prior to the Vlad TV interview he took part in the annual Minority Baseball Prospects HBCU All-Star game at Truist Park. The event is produced by Minority Prospects, an Atlanta-based organization which provides coaching, resources and services to minority baseball and softball players nationwide.

The program’s recent alums include Pittsburgh Pirates prospect Termarr Johnson, and Druw Jones, son of Quan’s favorite player. The organization also partnered with Atlanta Braves center fielder Michael Harris.

Quan was invited to throw out the first pitch. He spent time chatting up the prospects and taking photos with some of the nearly 500 kids gathered for a clinic.

“What stood out to me was how community-oriented he was,” said Reggie Hollins, a College Park native and president of Minority Prospects. “He never asked for any dollar amount to come out. He wanted to do it through his community pathway because someone did it for him.”

That someone was Monta, who comes from a line of Black mentors at parks like Gresham, Glenwood and Browns Mill. That list also includes C.J. Stewart, former MLB player and Hollins’ mentor, who founded L.E.A.D., an Atlanta-based mentoring program that seeks to help low-income Black youth through baseball. Stewart coached locally made MLB success stories Jason Heyward and Dexter Fowler. Hollins and Minority Prospects founder Alex Wyche were coached and mentored by Stewart.

Stewart was on hand to see Quan at the HBCU All-Star game that day. By that time, Quan had become a rap star but since his father was Stewart’s barber, the two men talked about the son’s baseball exploits often.

He could not overstate the impact of seeing Quan interact with kids looking up to a Black celebrity, whose passion for the game of baseball was only matched by their own. “It really allows Black boys to show up and be openly Black,” said Stewart, a former Chicago Cubs player and standout Westlake High School.

The visual also made Stewart think about what could’ve been.

“I just think about a level of regret that L.E.A.D. wasn’t around and set up while he was playing because we would’ve been actively seeking him out,” he said.

After his first pitch, Hollins remembers Quan staying to watch four innings of the game before heading off to another engagement. The event was such a hit that the Minority Prospects team and Quan’s camp discussed him performing at the event in 2025, or 2026.

Even in light of Quan’s death, the spirit of those plans are still in place. “We’ll continue to live out the legacy of what Rich Homie means to the Black community, the baseball community, and just the world, period, through our events,” Hollins said.

Atlanta is already celebrating its hometown hero. McNair High School held a balloon release in his honor Sunday.

Seeing his friend go from the timid kid in the batter’s box to a prized recruit, then an Atlanta hip-hop legend, is something Monta was proud to witness. He joked that if he had to compare Quan, the rapper, to a current MLB player, it would be Cincinnati Reds phenom Elly De La Cruz. “That’s Quan, man — the swagger,” he said.

Monta said a lot of people probably don’t know Quan’s baseball story, so he’s happy to share it. Quan, he believes, would want to see more kids who looked like him live out those pro dreams.

“I’m honored to be a person that was at the forefront of his business, and I was at the forefront of his baseball career,” he said.

Now, Coach Monta’s favorite player is diving for routine fly balls in heaven.

Read more stories like this by liking UATL on Facebook and following @itsUATL on X and Instagram.