Reclaiming the narrative of Br’er Rabbit

Just before one crosses Lake Oconee in Putnam County, Georgia, a gated property sits on the right side of the road. Blink at the wrong moment, and a state historical sign with information about a famous writer can get muddied in a blur of serene green fields rolling eastward on the Famous Authors Driving Tour.

Another sign noting the location as the Turnwold Plantation sits just a few feet away and informs visitors that this part of the tour is dedicated to Joel Chandler Harris, the white man who published the tales of quick-witted Br’er Rabbit in the 19th century.

However, other storytellers appear to be missing from the Turnwold Plantation plaque.

Enslaved griots were the originators of the tales of Br’er Rabbit, sharing adapted West African fables after long days working.

“Griot” is a term used to describe West African oral storytellers.

“This is Black History,” writer and historian Jim Auchmutey declared. “It comes with a little bit more complicated framing, but this is Black history.”

Harris encountered the griots of Turnwold Plantation in 1862 when he was hired as a printer’s apprentice at 16. After assisting the enslaver and owner of the estate of Joseph Addison Turner, Harris ventured to the cabins of enslaved African Americans to hear tales “about critters.”

“He would go down to the old slave cabins, he would sit and listen to those stories,” said Lynda Walker, director of the Uncle Remus Museum in Harris’ hometown of Eatonton.

“He was fascinated by them,” Auchmutey said. “The underlying theme of [the fables] is that animals, like rabbits who are prey, are being really clever and outsmarting the people who are trying to get them. It doesn’t take a scientist to figure out that that has a lot of resonance for people who are living in slavery.”

In the stories of Br’er Rabbit, the trickster always finds a way to outsmart his would-be captors, Br’er Fox and Br’er Bear.

Storyteller Gwendolyn Napier of The Wren’s Nest in Atlanta, the house museum where Harris relocated after leaving Eatonton, said Br’er Rabbit serves as an unmistakable metaphor.

“When you think about how those stories are twisted and told, it was always the rabbit who took time to outwit everyone. And I ask this question all the time to my audience, ‘Who do you think the rabbit was really? The enslaved individual or the master?’” she challenged. “They always said, ‘The enslaved.’”

She said that Br’er Rabbit’s character had to be wiser than his enemies.

“The enslaved people were not ignorant,” Napier explained, donning an ensemble of jewelry made of cowrie shells. “They knew ways of really coming out of all the mess that they were going through. So, the stories had, in my opinion … a very significant message.”

Auchmutey, a member of the advisory council of The Wren’s Nest and former writer with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, explained that the storytellers included an “Aunt” Minervy and “Old” Harbert.

Storyteller Georgia Smith of the Uncle Remus Museum in Eatonton said she learned about a woman called “Aunt” Chrissy while growing up as a Black child in segregated Eatonton.

“We were taught these stories were African folktales and … that we should tell our history, we should pass it down to the family,” Smith said. “So, that’s what we always did. When I was a child, everybody was a storyteller.”

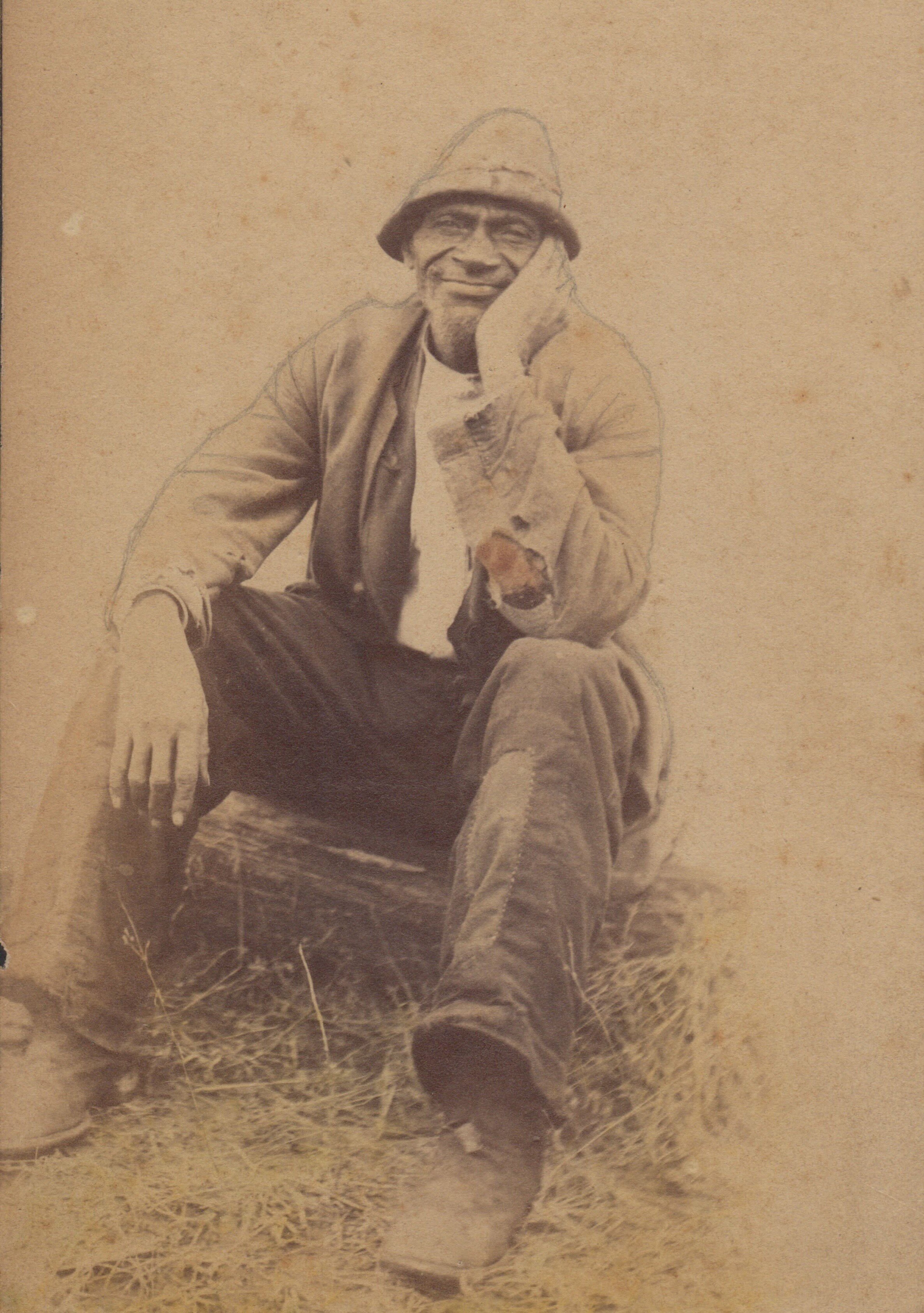

Neither of the historians could place the fifth griot of Turnwold, but both Auchmutey and Smith agreed that “Uncle” George Terrell was the main inspiration behind the creation of Harris’ character “Uncle Remus,” a storybook amalgamation of the enslaved narrators.

“George Terrell is by far the best known one,” Auchmutey said.

Auchmutey explained that reporters went to interview Terrell after stories of Br’er Rabbit became popular in the 1880s, a period after the Civil War when many other formerly enslaved people engaged in the Great Migration. However, Terrell stayed put at Turnwold.

“I don’t know how old he was, but I’m sure he was a pretty elderly gentleman at that time,” Auchmutey said. “Like a lot of Black people who had been enslaved in the South, after Emancipation they didn’t know anything else. They stayed pretty close to home.”

Not much else is known about the tellers of tales at Turnwold, but the stories they shared have spread into cultural phenomena that are still enjoyed around the world.

The books have been translated in 20 languages around the world, and historians have speculated that the characters Peter Rabbit and Bugs Bunny were inspired by Br’er Rabbit.

Disney also bought the rights to the stories and made the film “Song of the South” in 1946. Unfortunately, Auchmutey said, that version distorted the integrity of the Br’er Rabbit African folktales by creating a narrative around a happy formerly enslaved man who became a sharecropper and joyously spent his free time telling stories to white children.

“There are a million ways to imagine now how they could have told that story better,” Auchmutey said. “But in the context of that time, if they had just made him not seem so damn happy-go-lucky about being a former slave, that probably would’ve helped.”

To ensure Br’er Rabbit’s cultural accuracy, Auchmutey said The Wren’s Nest changed the focus on the narrative and solely hired Black orators. Beginning in the 1980s, Black civil rights leaders, like Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, joined the museum board, followed by the likes of John Lewis and Michael Lomax.

“As a storyteller, I can be stuck with hatred. I can be stuck with racism all of my life, but I’m trying to show the next generation how to move on a little bit,” Napier said, comparing the Black American experience to the mythological Sankofa bird.

“I’m like the Sankofa bird: I’m looking back, I never forget,” she said. “This bird is always looking back at what happened in the past, but you have to look back to see what’s in the future.”

Still today, Napier said Black people can relate to Br’er Rabbit when they get stuck in housing and food crises. She said racial injustice is another “obstacle,” but channeling the will and strength of African American ancestors can prove triumphant.

And channeling the wisdom of the Turnwold griots who pushed Br’er Rabbit into an evolutionary international icon has given Napier a sense of self.

“Each time I stand right here before I tell a story, I always focus right here and he reminds me of why I am here,” Napier said, standing in front of a central portrait of Terrell at The Wren’s Nest.

“I know who I am as a storyteller, I know my purpose on this earth as an African American person.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year’s AJC Black History Month series, marking its 10th year, focuses on the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and the overwhelming influence that has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout February in the paper and on AJC.com and AJC.com/news/atlanta-black-history.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.