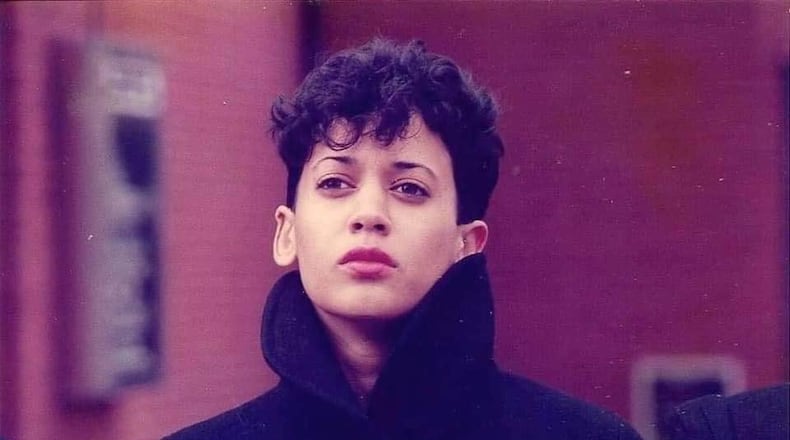

Sometime around 1991 when Takiia Anderson was a student ambassador giving tours around Howard University, she caught the eye of a parent.

The mother of an incoming basketball player from Georgia was impressed with Anderson’s poise, grace and confidence, and wanted to tell her.

“She was an educator, but I remember she wanted to talk about politics,” said Anderson, a native of Boston who graduated from Howard in 1994. “She told me that I could be anything I wanted to be. That I can be the first Black woman to be president of the United States.”

Anderson laughed then about the possibility of a girl from Howard University, becoming president. Now, 33 years later, she is not laughing anymore.

Kamala Harris, who arrived at Howard in the fall of 1982, about a decade before Anderson, is locked in a tight two-person race for the White House as the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate.

With her rival, former President Donald Trump, making a push to win over Black male voters, Harris is hoping her bona fides as a graduate of a historically Black college will prove persuasive.

Credit: Howard University

Credit: Howard University

Harris’ origin story is deeply connected to her experiences at Howard, one of the premier colleges in America, which also happens to be an HBCU.

If she is elected, she would be only the second Black president of the United States and the first to graduate from a Black college. Trump, attended the University of Pennsylvania.

“Howard has many notable graduates and we are no strangers to this. I don’t mean to sound arrogant, but I am not shocked as a Bison,” said Erin White, a 1998 graduate of Howard. “We always knew who we were. We know that this is what we are capable of. We have always been ready for the moment.”

The Mecca

Atlanta is the home of the highest concentration of HBCUs in the country with the likes of Spelman College, Morehouse College, and Clark Atlanta University. Their rankings, powerful alumni, and substantial endowments, relative to other Black colleges often dominate the conversation.

But for nearly 160 years, Howard has cast one of HBCU’s most significant shadows by playing an integral role in shaping America’s Black middle class and its thinking about race, culture and class.

When Cheryl Gill Riley, who grew up in Queens, New York, was bused to all-white schools, she found refuge in history books and the Black community that her parents built around her. The common denominator was Howard.

“I would pick up the encyclopedia and every notable Black person went to Howard. My doctors and dentists went to Howard,” said Riley, who graduated from the school in 1980 and would go on to create Howard Moms Student and Parent Advocacy for parents struggling with questions about navigating the school. “I always heard about Howard and I knew it represented something different.”

Credit: Cheryl Gill Riley

Credit: Cheryl Gill Riley

The school was founded by Union Civil War hero and Freedmen’s Bureau Commissioner Gen. Oliver Otis Howard through an act of Congress in 1867, just two years after the end of the war and the abolishment of slavery.

Five of the nine Black Greek fraternities and sororities — including Harris’ Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Inc. — were launched on Howard’s campus in Washington D.C.

In 1954, when the Supreme Court decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case declared the “separate but equal” doctrine unconstitutional, it was because of the work of Charles Hamilton Houston, the former dean of Howard Law School and his star pupil, Thurgood Marshall, who went on to become the first Black associate justice of the United States Supreme Court.

In her memoir, “The Truths We Hold: An American Journey,” Harris wrote about her lifelong interest in law and how, when deciding on a college, she wanted her career to “get off on the right foot. And what better place to do that than at Thurgood Marshall’s alma mater?”

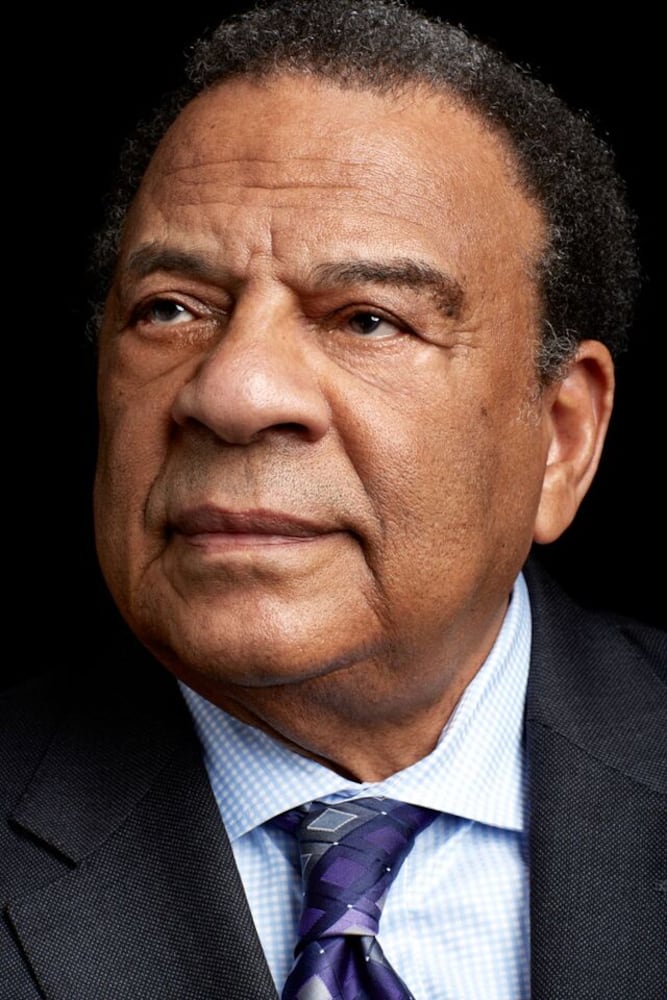

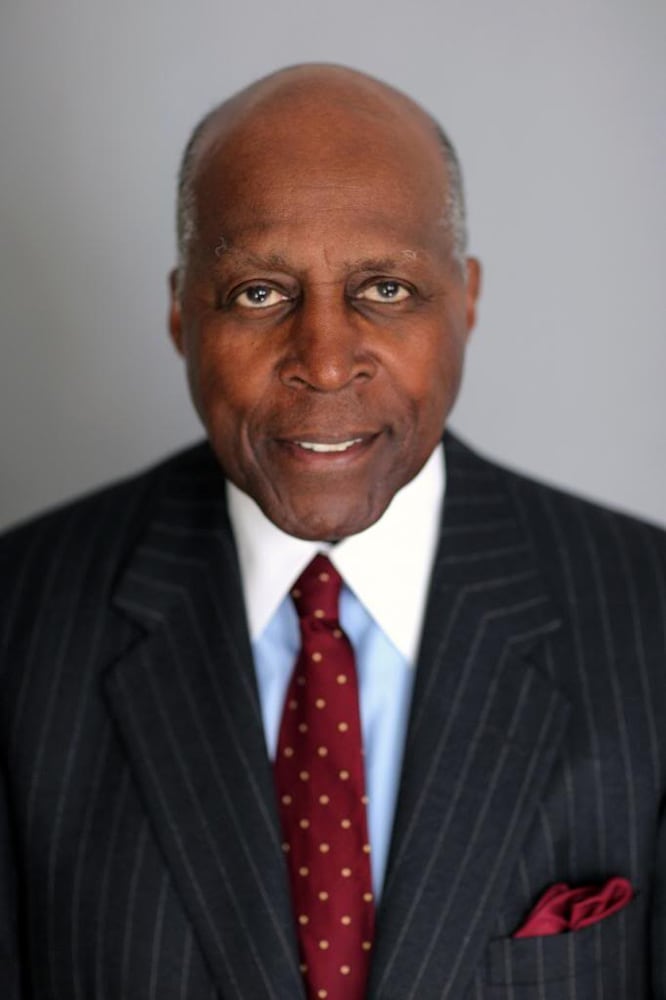

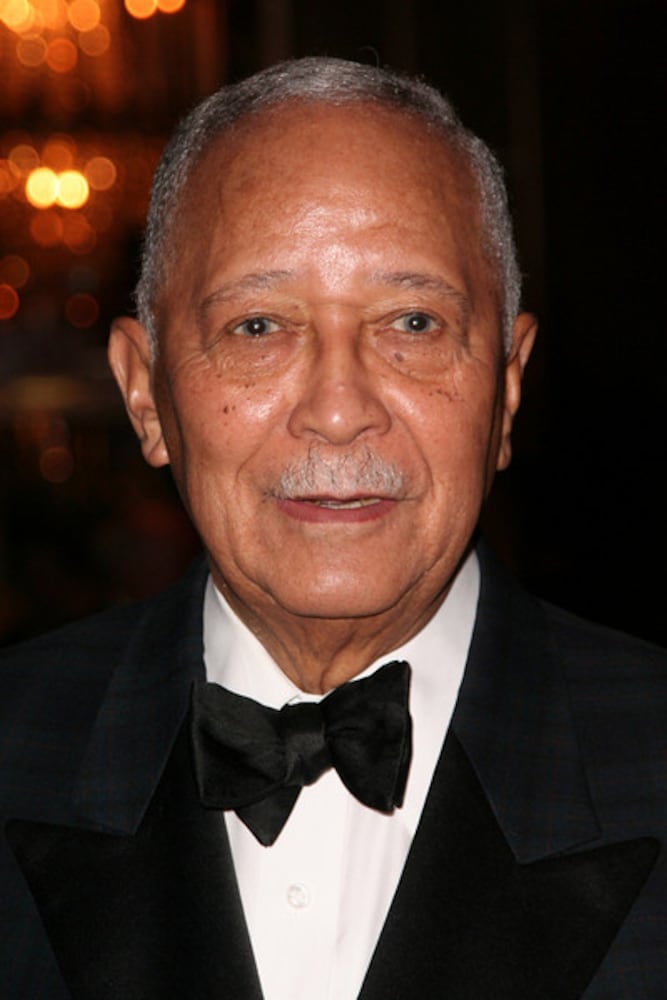

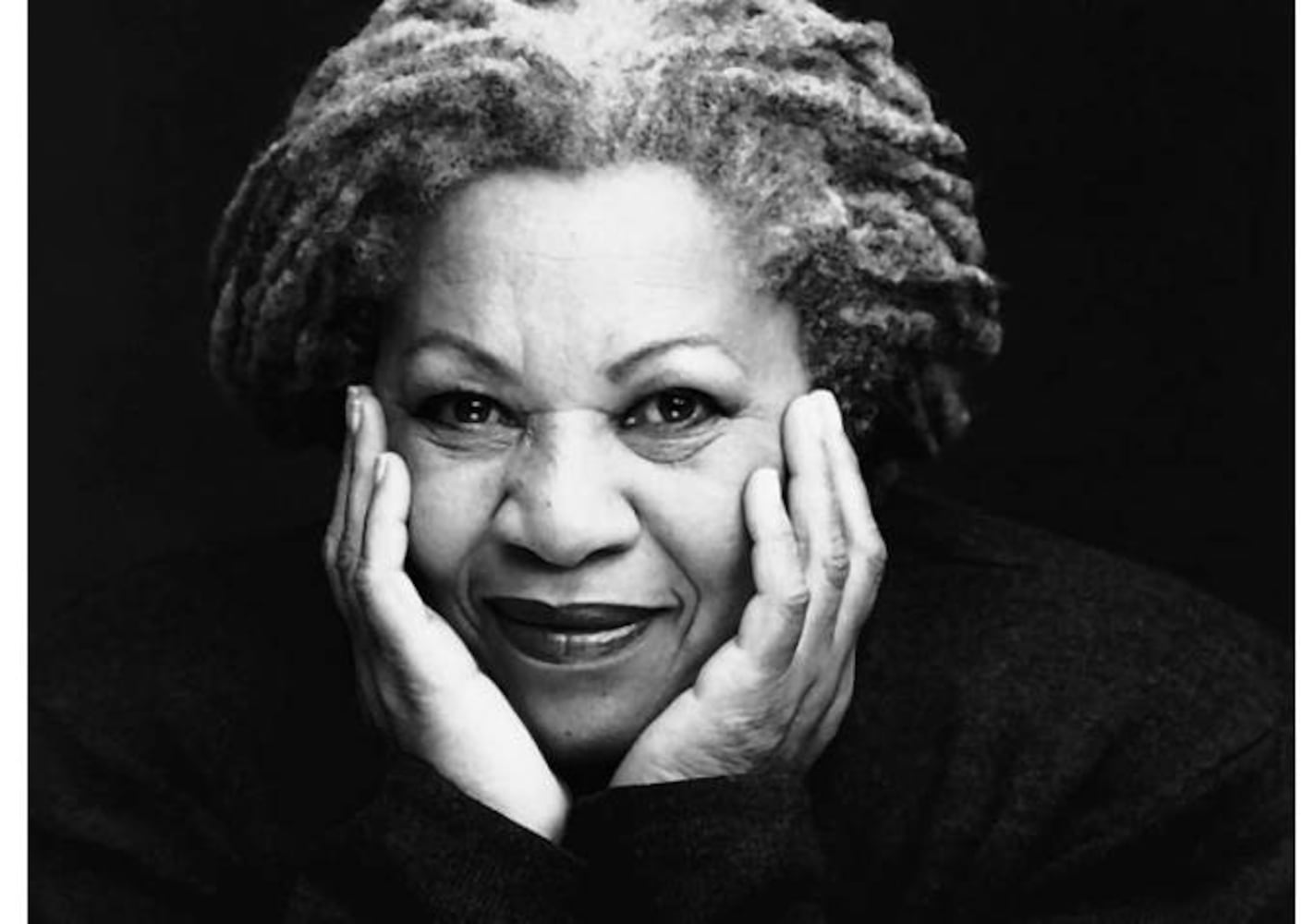

Along with Marshall, Howard alums have included, Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winner Toni Morrison; Pulitzer Prize winner Isabel Wilkerson; sociologist E. Franklin Frazier; politicians Patricia Roberts Harris, Vernon Jordan, Edward Brooke and David Dinkins; and entertainers Roberta Flack, Phylicia Rashad, Debbie Allen and Chadwick Boseman.

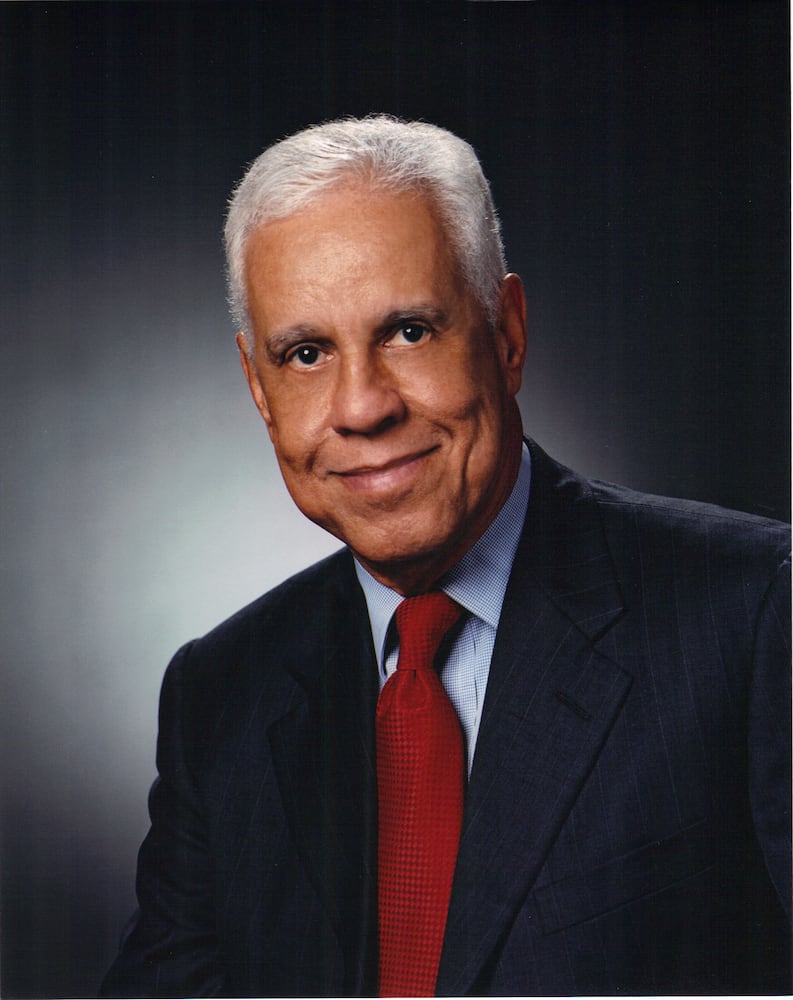

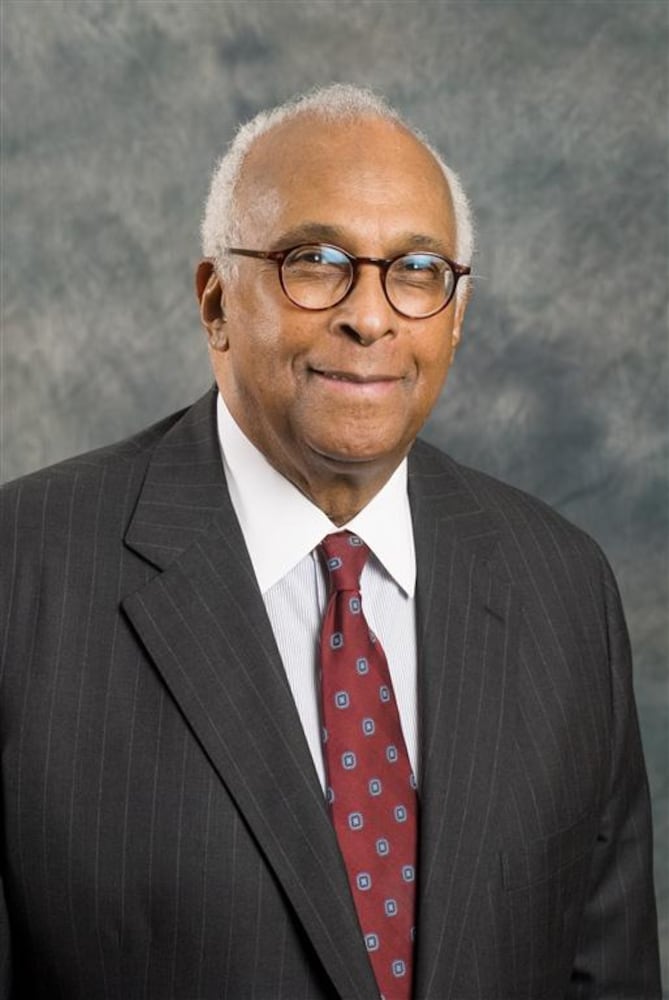

Since 1974, Atlanta has had an unbroken streak of Black people who have served as mayor. Of the seven people who have been elected, three — Andrew Young, Shirley Franklin and Kasim Reed — are Howard graduates.

“You can find your tribe at Howard,” said Nina Hickson, a former Atlanta city attorney and chief presiding judge for the Fulton County Juvenile Court, who graduated in 1981. “Because of the heritage and history of the people who attended, it was a wonderful place to learn and grow. It eliminated the need to have to overcome low expectations and folks doubting you because of your race.”

Credit: Nina Hickson

Credit: Nina Hickson

With more than 10,000 students across undergraduate and professional schools, Howard is one of the largest HBCUs in the country. It is also the most comprehensive with an executive MBA program and colleges of dentistry, law, medicine and pharmacy.

In the recently released U.S. News & World Report 2025 Best Colleges rankings, while Spelman still ranks as the nation’s top HBCU, Howard was second. But in the magazine’s overall rankings, Howard was the only HBCU listed as one of the nation’s top 100 universities, clocking in at No. 86.

Forbes recently ranked Howard as the No. 1 Black college in the nation.

With all of that, Howard has picked up the moniker, “The Black Harvard.”

It is a name that most graduates reject, as it implies the school is great only among Black institutions. Instead, they prefer, “The Mecca,” a name that still plays on the school’s elitism, but puts it in a Black context.

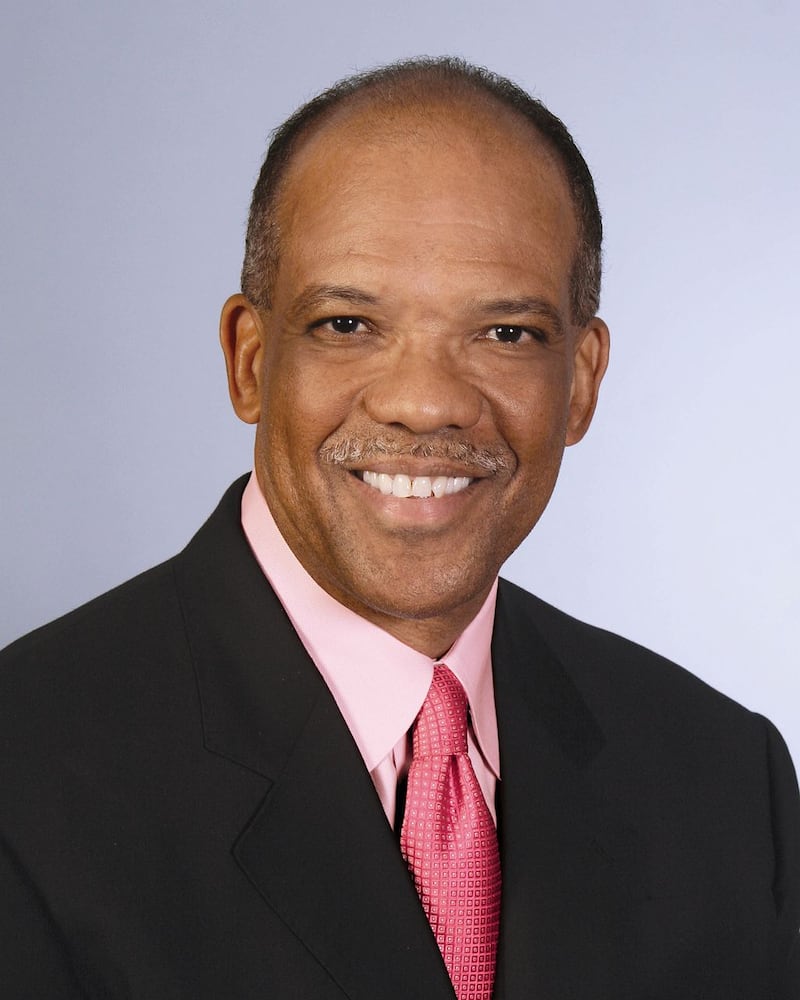

Credit: Ivan Thomas

Credit: Ivan Thomas

“We have a certain panache about us. The first time I stepped on the campus, I was blown away,” said Ivan Thomas, who graduated in 2008, years after his father graduated in 1984. “I will never forget hearing reggae music blasting and meeting Black people from all over the world — Compton, Chicago, Trinidad, Cuba.”

Harris’ Howard

Harris came to Howard after graduating from an all-white high school in Canada and spending a year at Vanier College in the Saint-Laurent borough of Montreal.

She quickly established herself by joining the debate team and getting elected freshman class representative of the liberal Arts Student Council. She was heavily involved in campus activism, participating in anti-apartheid demonstrations and campus sit-ins. It wasn’t until her senior year in 1986 that she had time to pledge AKA.

Credit: Howard University Alpha Kappa Alpha Archives

Credit: Howard University Alpha Kappa Alpha Archives

Melanie Felton saw it all as Harris’ freshman classmate.

“I felt like she was extremely smart, pretty and friendly. Completely down to earth,” said Felton, who graduated in 1987. “I never saw her as untouchable.”

Unlike Harris, who came to Howard to chart her own path, Felton’s path there was built on the school’s legacy. Her grandmother, father, two brothers and an older sister all attended Howard.

Even Felton’s husband, former University of Georgia head basketball coach Dennis Felton, is an alum.

“I always knew I was going to go to Howard,” Felton said. “Growing up in Massachusetts, in a community of white and Hispanics, I never experienced people of color wanting the same things I wanted. I just felt like it was home and a place for comfort.”

Pia Forbes, a communications specialist in Atlanta, who attended Howard at the same time as Harris and Felton, said the vice president is living proof that “tropes about Black colleges being second-rate are erroneous.”

Credit: Pia Forbes

Credit: Pia Forbes

“People will start to see HBCUs as viable, excellent options, that even Black people couldn’t quite grasp,” said Forbes, who graduated from Howard in 1987. “If a woman can ascend to the presidency, having matriculated through an HBCU, there is nothing that little Black boys and girls cannot do.”

Howard has remained with Harris. As a U.S. Senator in 2017, she delivered its commencement address and in 2019, on the day she announced her first run for president, she held her opening news conference on campus.

After Harris dropped out of the 2020 race, Joe Biden picked her to be his running mate.

Credit: Jamie Spaar for the AJC

Credit: Jamie Spaar for the AJC

“I don’t think it was negligible that his running mate was a Howard grad,” said Mansa King, a sociologist at Morehouse and a 1997 Howard graduate.

On the Sunday in July, when President Biden called her to say that he would not seek reelection and endorsed her as the Democratic presidential nominee, she happened to be wearing a hooded Howard sweatshirt.

“I will never forget that Sunday when Biden stepped down,” said Shanikka Wagner, who graduated in 2000 and grew up in Daly City, California, not far from where Harris is from in the Bay Area. “I knew that Howard had prepared her for that moment … And I started crying.”

Credit: Shanikka Wagner

Credit: Shanikka Wagner

The Real World

Harris’ political rise has no doubt placed a spotlight on the school, as well as HBCUs, which have a lot at stake in this election.

In September, the Biden administration announced $1.3 billion in additional federal investments in HBCUs. In total, the administration provided more than $17 billion into HBCUs.

In 2019, while Trump was in office, he signed a bill that reauthorized $225 million in mandatory funding to minority-serving institutions. Only $85 million in recurring funds was allocated for HBCUs.

Still, Trump has been reaching out to young Black men and shown some strength.

Seeing the importance of the Black college vote, the Harris-Walz campaign recently announced a “Homecoming Tour Across Battleground States,” where surrogates will visit HBCUs in Georgia, North Carolina, Florida, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, during their most critical times — homecoming.

The tour will stop at Clark Atlanta Saturday and Morehouse and Spelman on Oct. 26

‘She is a Bison’

Across the country, thousands of Howard alumni have rallied behind Harris by leading fundraising efforts and working to mobilize voters.

In Atlanta, the Howard University Alumni Club of Atlanta has stopped short of officially supporting Harris, because of university restrictions, but as individuals, they have been all in.

“Anyone would just have to look at who we have in play and make a thoughtful and intelligent decision on who would be the best person to lead the country forward. And that is Kamala,” said Erin White, president of HUACA and a 1998 graduate.

White estimates that there are about 6,000 Howard alumni in the Atlanta area, making it one of the largest pools of graduates in the country.

On Sept. 10, many of them crammed into alumna Karimah McFarlane’s Buckhead Art & Company to watch the Harris-Trump presidential debate.

Credit: Melanie Felton

Credit: Melanie Felton

“You could hear a pin drop when she was talking,” White said.

Some members of the HUACA are planning a fleet of buses — mostly filled with Howard graduates — to attend the inauguration.

But not everybody is on board.

Mansa B. King was a student in 1994 when Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first Black president, spoke at Howard’s commencement. King, who graduated in 1997, said while he is proud of Harris as a Bison, he doesn’t agree with her position on global affairs, particularly as they relate to the Isreal-Hamas War.

He will not be voting for her.

Credit: Morehouse College

Credit: Morehouse College

“I am not a fan because of what I learned at Howard,” said King, who is supporting the Green Party and Cornel West. “Howard internationalized my definition of Blackness. It sharpened my knowledge base and theoretical lens so that I could understand what was going on in the world. It is the same reason I didn’t vote for (Barack) Obama.”

But on Nov. 5, Tamara Irving, a dance consultant who graduated from Howard in 1998, will take her daughter, who is applying to Howard next fall, to the polls for the first time to vote.

“We are just so excited to know that she was a part of our university and she could be our first female president,” Irving said. “Even before this, you couldn’t tell us that we weren’t excellent. You can’t tell us nothing now.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured