Georgia native establishes first Black-owned record label in 1921

In May 1921 — decades before Atlanta-based companies like Big Oomp Records, LaFace Records, So So Def Recordings, Quality Control Music and Love Renaissance all achieved success and developed local talent into superstars — music executive Harry Pace had a vision to start Black Swan Records, a record company that released music by Black musicians and performers across genres for Black listeners.

The Covington native set up operations from his basement in Harlem, New York, during the early stages of the Harlem Renaissance, a Black artistic and literary movement. His Black Swan Records put out jazz, gospel, blues and classical records and is credited as the first Black-owned and -operated record company in the U.S.

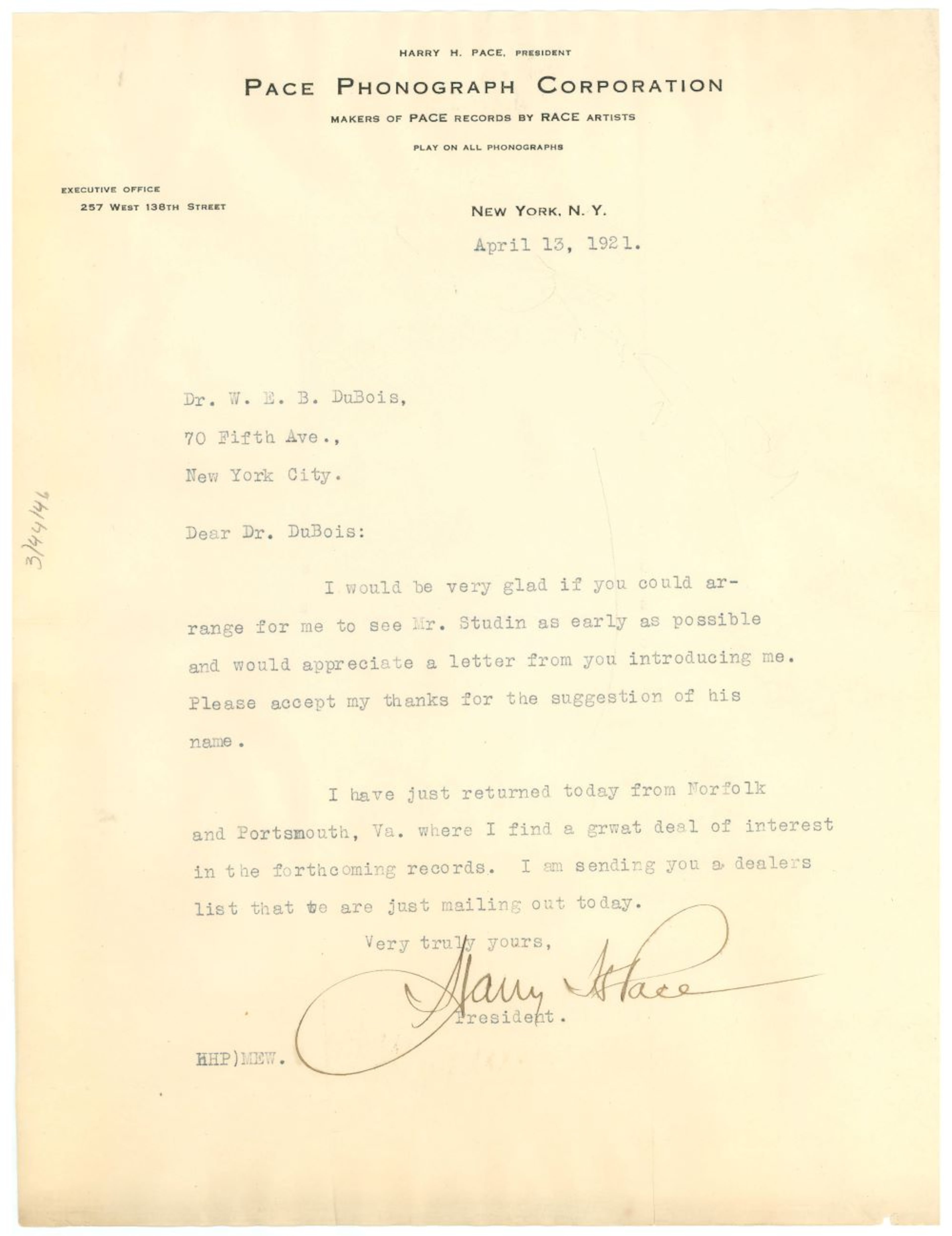

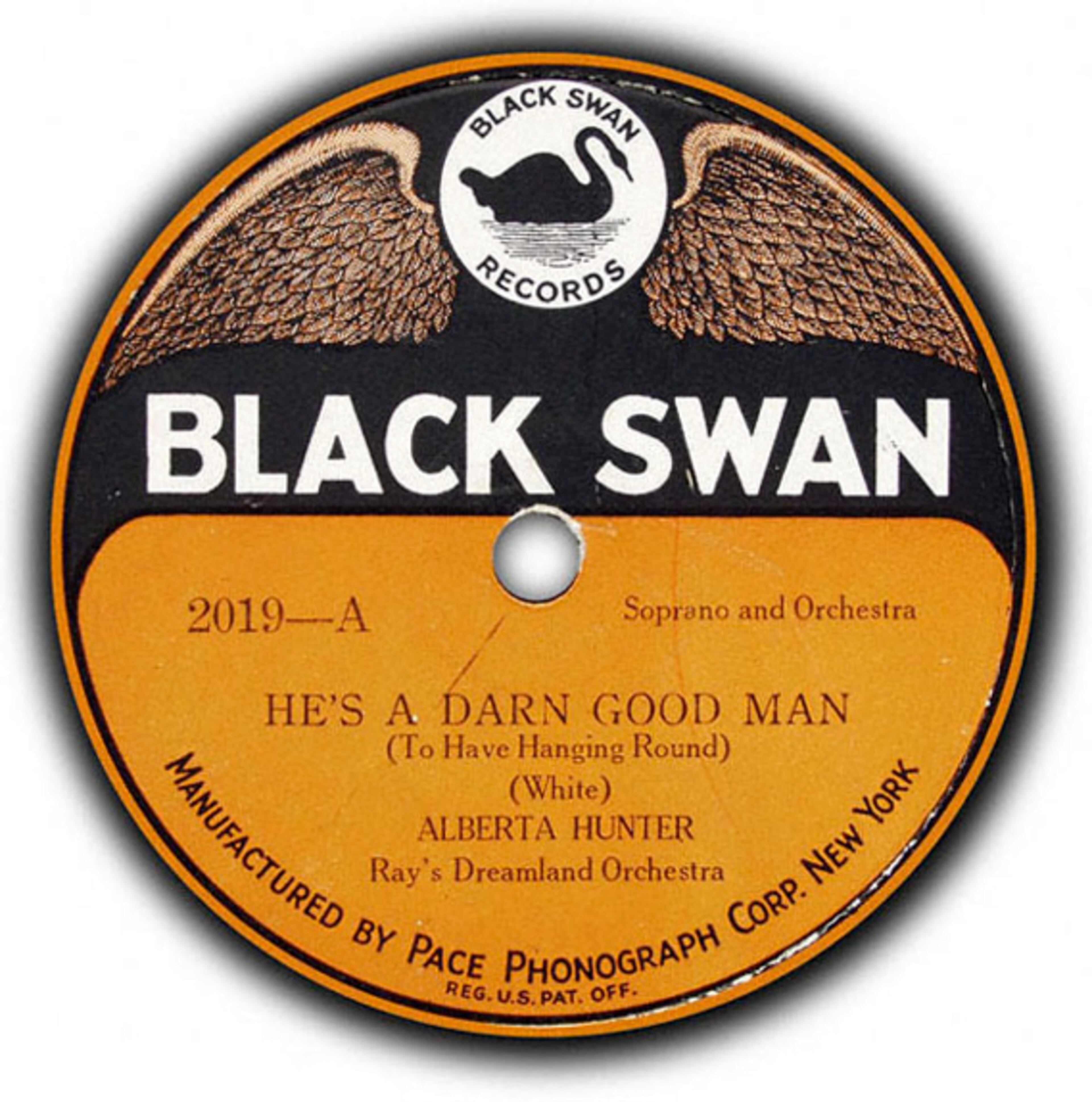

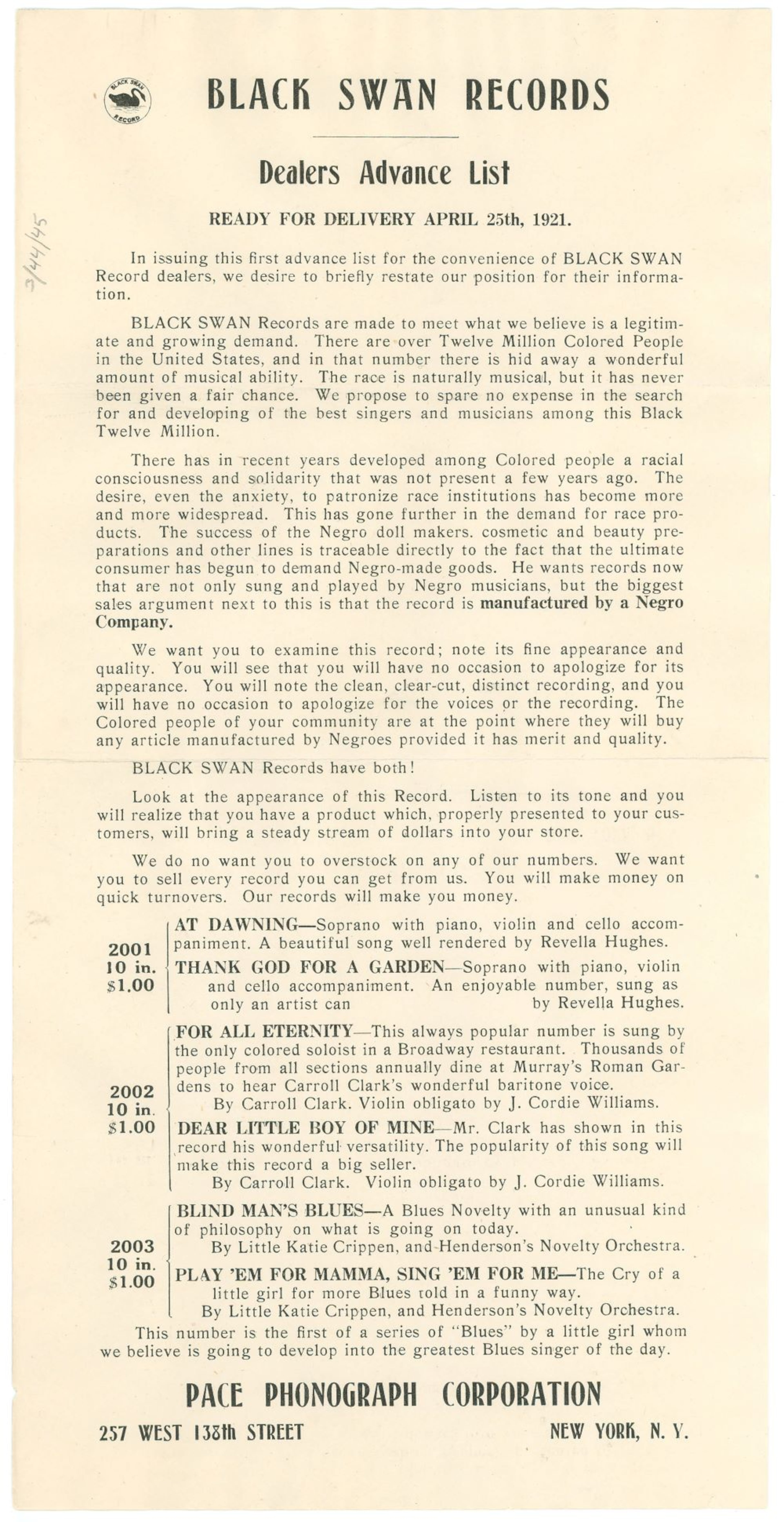

The record label — named after Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, an opera singer nicknamed “The Black Swan” — had its own pressing plant, Pace Phonograph Corporation, to cut its releases.

Eric Pace, Harry Pace’s great-grandson, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution the trailblazing label head was determined to execute his ideas despite the adversity he knew he would encounter. “He was an accomplished man who was into all different styles of music and knew African Americans were capable of doing it all, but he understood that the white industry would try to hold him back.”

Pace’s label arrived at a time when Jim Crow laws legally restricted Black communities from having access to equal opportunities. Before Black Swan Records opened, white-owned record companies like RCA, Columbia and Victor typically recorded novelty singles by white performers disguised as minstrels or just didn’t sign Black artists to their rosters.

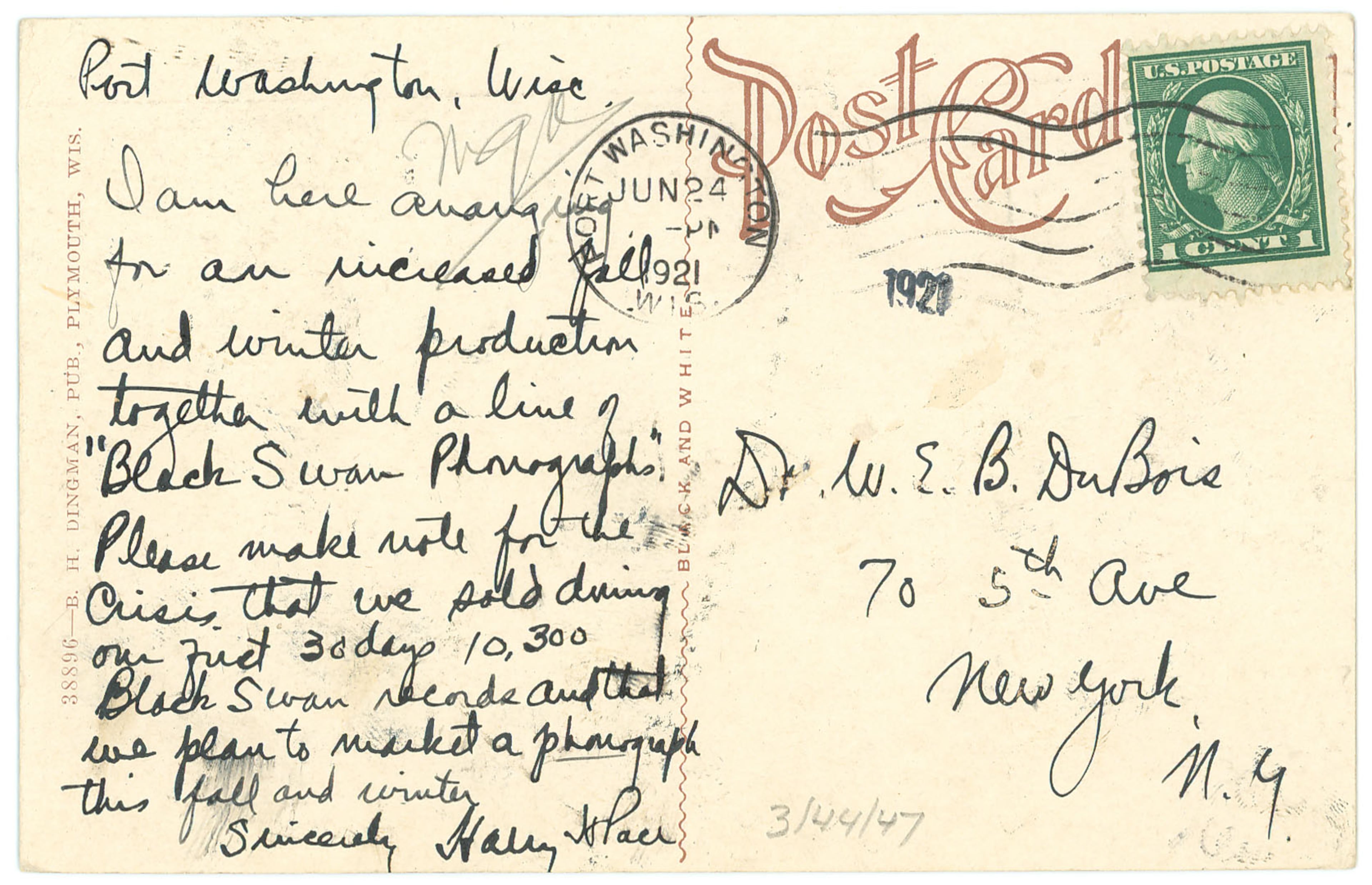

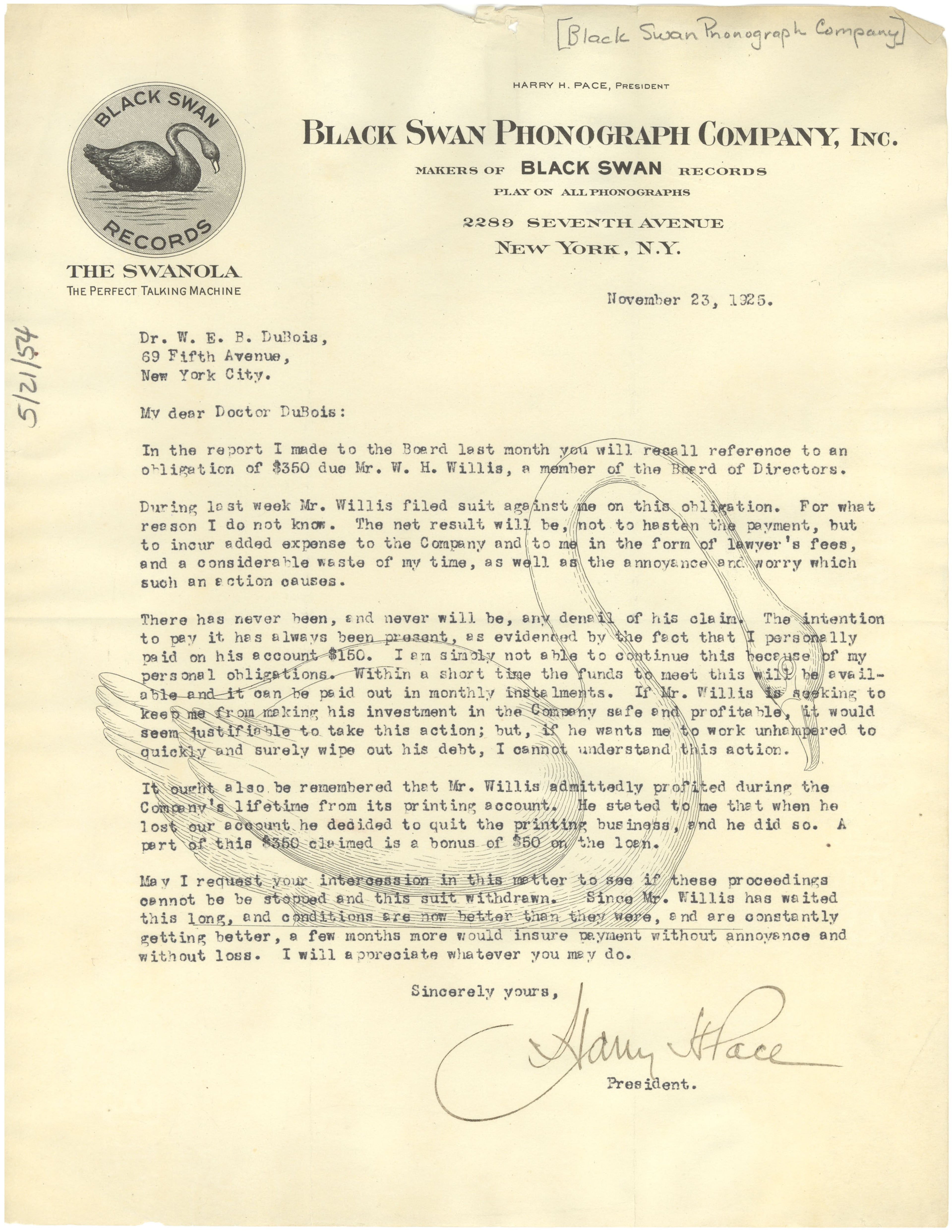

Pace, who studied under scholar and writer W.E.B. Du Bois at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta) in the early 1900s, built a dynamic roster that included blues singers Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter, opera singer Revella Hughes and baritone Carroll Clark.

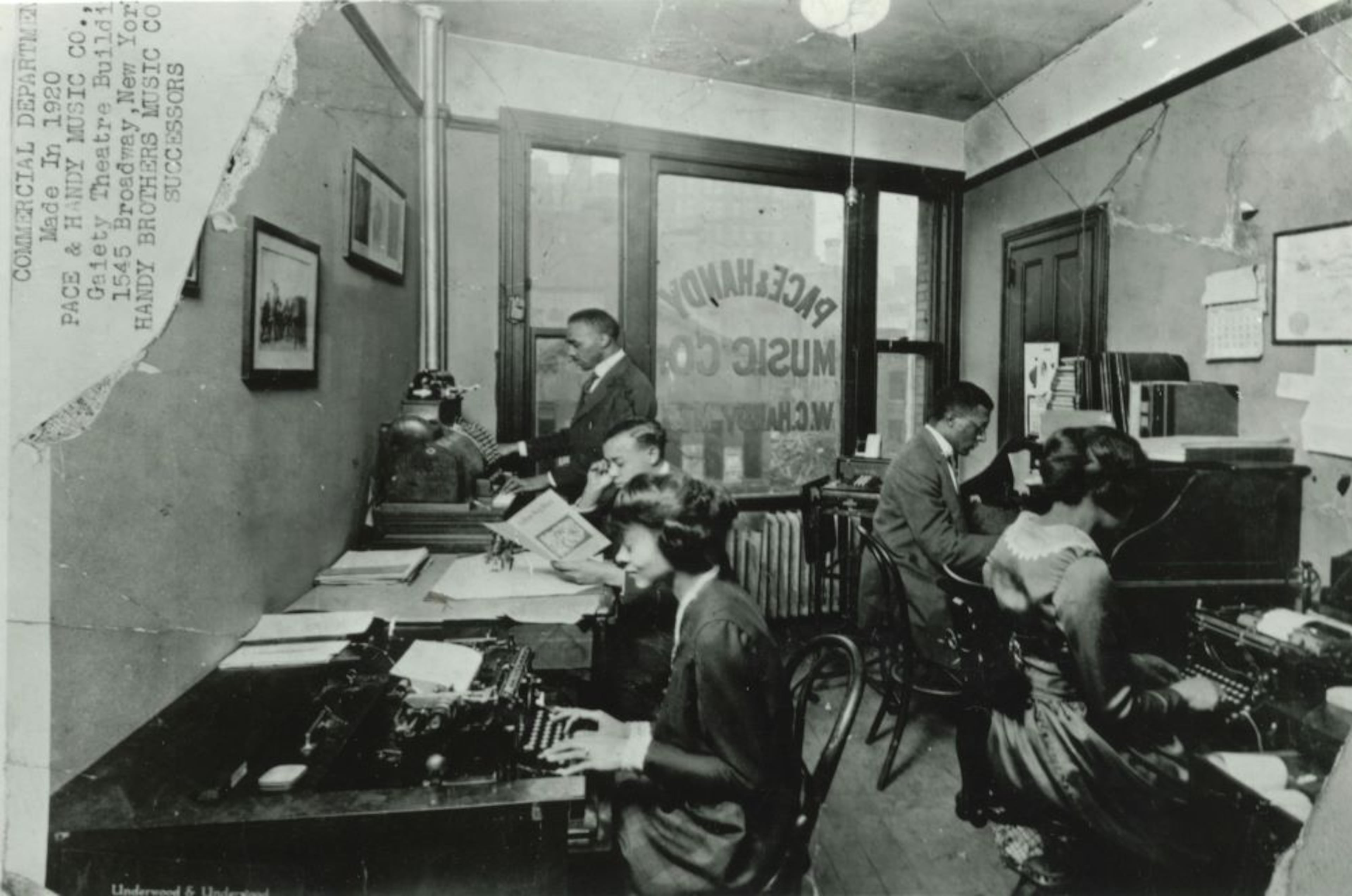

To give Black Swan Records infrastructure, Pace recruited Du Bois as chairman of the board of directors. He retained employees from Pace and Handy Music Company, the publishing company he co-founded with composer W.C. Handy in the mid-1910s, as the label’s staff.

Pace brought in composer William Grant Still as an arranger; pianist and swing music pioneer Fletcher Henderson as musical director and bandleader; and Paul Robeson as a company salesperson.

DuJuan Morris, African American history professor at Clark Atlanta University and Spelman College, said Pace — who co-chartered the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP in 1917 — made creative and business decisions purposed to create social mobility for the Black community. It was during a period when successful Black-owned businesses in the South and Midwest were regularly being vandalized or burned by white mobsters.

“He came into the industry with this idea of racial uplift, self-determination and championing his community. Instead of caving in to the obstacles, he used them as fuel to forge ahead in the midst of economic and violent oppression,” Morris said.

“Down Home Blues,” Waters’ debut recording on Black Swan Records, was the company’s first major hit with Black and white audiences. Pace capitalized on its success by booking the Black Swan Troubadours — a revue led by Waters and Henderson and briefly featuring boxer Jack Johnson — to tour the “chitlin circuit,” a series of venues that allowed Black musicians to perform in front of Black audiences.

Pace, business manager for Moon Illustrated Weekly, one of the first magazines published by and targeting Black audiences, utilized his relationships with Black newspaper staffs and editors to help place ads, publicize new releases and concert dates. Paul Slade, the author of 2021’s “Black Swan Blues: The Hard Rise and Brutal Fall of America’s First Black-Owned Record Label,” said Pace relied on his charisma and vast network to help spread the word about Black Swan’s output.

“He started the label on a shoestring, so he wasn’t in a position to spend a lot of money on advertising,” Slade said. “He sent out attractive press releases, and the editorial teams thought he had an extraordinary enterprise and always operated with good character and integrity when he conducted business. He was a sharp cookie.”

And Black Swan Records kept its momentum going.

The label released music from “Shuffle Along,” which in 1921 became the first Broadway production to feature a majority Black cast, and the first recording of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” credited as the “Black national anthem” and written by James Weldon Johnson and his brother, John Rosamond Johnson.

Pace’s business savvy caused so much disruption in the music industry that white retailers, distributors and record companies made several attempts to sabotage and silence their competition.

Vendors started returning unopened boxes of Black Swan vinyl to Pace’s office. In Slade’s book, he writes that Black bodies were lynched, thrown and left in the lobbies of concert venues ahead of the Black Swan Troubadours’ performances in the South.

One newspaper reported a bomb threat in a lump of coal that was shipped to the pressing plant. White record executives were using underhanded schemes to sign Black Swan artists, musicians and other Black performers to their rosters.

Morris said Pace’s ability to serve Black and white consumers was a threat to the recording industry.

“He was prominent and represented successful Black manhood and advancement, but there was this fear of Black dominance from Pace’s critics who wanted to chop down his image,” Morris said.

Changes in technology also affected Black Swan’s fate. The rise of radio caused phonograph sales to drop, which left Black Swan with staggering debt and forced to declare bankruptcy.

In 1924, Pace closed Black Swan Records. He sold the company’s music catalog to Paramount Records and relocated to Chicago, where he pivoted into successful careers as an insurance salesperson and civil rights attorney.

He went on to provide legal counsel for real estate broker Carl Hansberry in Hansberry v. Lee, a 1940 U.S. Supreme Court case that ended housing discrimination in Chicago and served as the motivation behind “A Raisin in the Sun,” written by Hansberry’s daughter, Lorraine.

He mentored John Johnson, the founder and publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines, until Pace died on July 19, 1943, at age 59.

Despite only operating for three years, Black Swan Records proved there was a market for Black music lovers to enjoy all styles of music from Black performers. Keinon Johnson, former Interscope Records executive and Clark Atlanta alumnus, said Pace’s legacy created a blueprint that allowed Johnson to have a career as a Black music executive.

“He’s one of the original pioneers of the ‘find a way or make one’ spirit I’m able to carry with me,” Johnson said.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year’s AJC Black History Month series, marking its 10th year, focuses on the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and the overwhelming influence that has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout February in the paper and on AJC.com and AJC.com/news/atlanta-black-history.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.