Atlanta Unveiled: 10 historic moments that shaped Atlanta

Since 2016, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution has marked Black History Month with a daily series that has tried to capture the essence of Black culture while telling untold and amazing stories.

What better place to find and tell those stories than Atlanta, which has been called everything from “The cradle of the modern Civil Rights Movement” to “The Black Mecca.”

The overall theme of this year’s series is “Atlanta Unveiled: How African Americans Shaped Our City.”

In the 10 years we have been doing this series, we have produced more than 300 pieces of original content, and throughout the month we will highlight some of our best work.

Today, in the spirit of Atlanta (and Georgia), here are 10 landmark moments.

The arrival of Maynard Jackson

In 1975, while Atlanta was in the middle of a historic $500 million expansion of then-Hartsfield Atlanta Airport, Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, noticed that white architectural and engineering firms held all of the lucrative airport contracts for more than a decade without rebids. He announced renegotiations for long-standing contracts and threatened to delay the airport’s designing, planning and construction unless minorities got involved.

“It’s a question of doing what’s right and not pussyfooting around,” Jackson said. “I’m sick and tired of hypocrisy.”

By 1980, the world’s largest passenger terminal opened. Minority companies participated in 25% to 30% of the work. Some 23 years later, the airport, the world’s busiest, was renamed Hartsfield–Jackson International Airport.

A symbol of educational excellence

The Atlanta University Center is the largest concentration of Black institutions of higher education in the country and has educated some of the country’s most gifted minds. Located in southwest Atlanta, the AUC includes Morehouse College, Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, Morehouse School of Medicine, Morris Brown College and the Interdenominational Theological Center.

Many of the schools’ beginnings date back to the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, offering educational opportunities for the sons and daughters of newly freed enslaved people.

The great laundry workers’ strike of 1881

Imagine it is 1881 and each day you gather up the soiled sheets, shirts, diapers and underpants of another family. You go from house to house doing this until you have a mound of stinking, dirty laundry that you tie into a giant bundle and hoist atop of your head.

Then you walk a mile, maybe two, joined along the way by other Black women bearing similar loads. Eventually, you come to a backyard dotted with cauldrons. You make the lye soap by hand. You haul the water to fill the cauldrons and build fires to heat the water. Then you spend hours beating the clothes in the hot soapy water with a big wooden paddle.

But your work as a laundress or “washer woman” has only begun.

There’s still drying, ironing, folding and delivery to do. You do all of that for as little as $8 a month. Then you do it again.

Until you and the other Black women decide to go on strike.

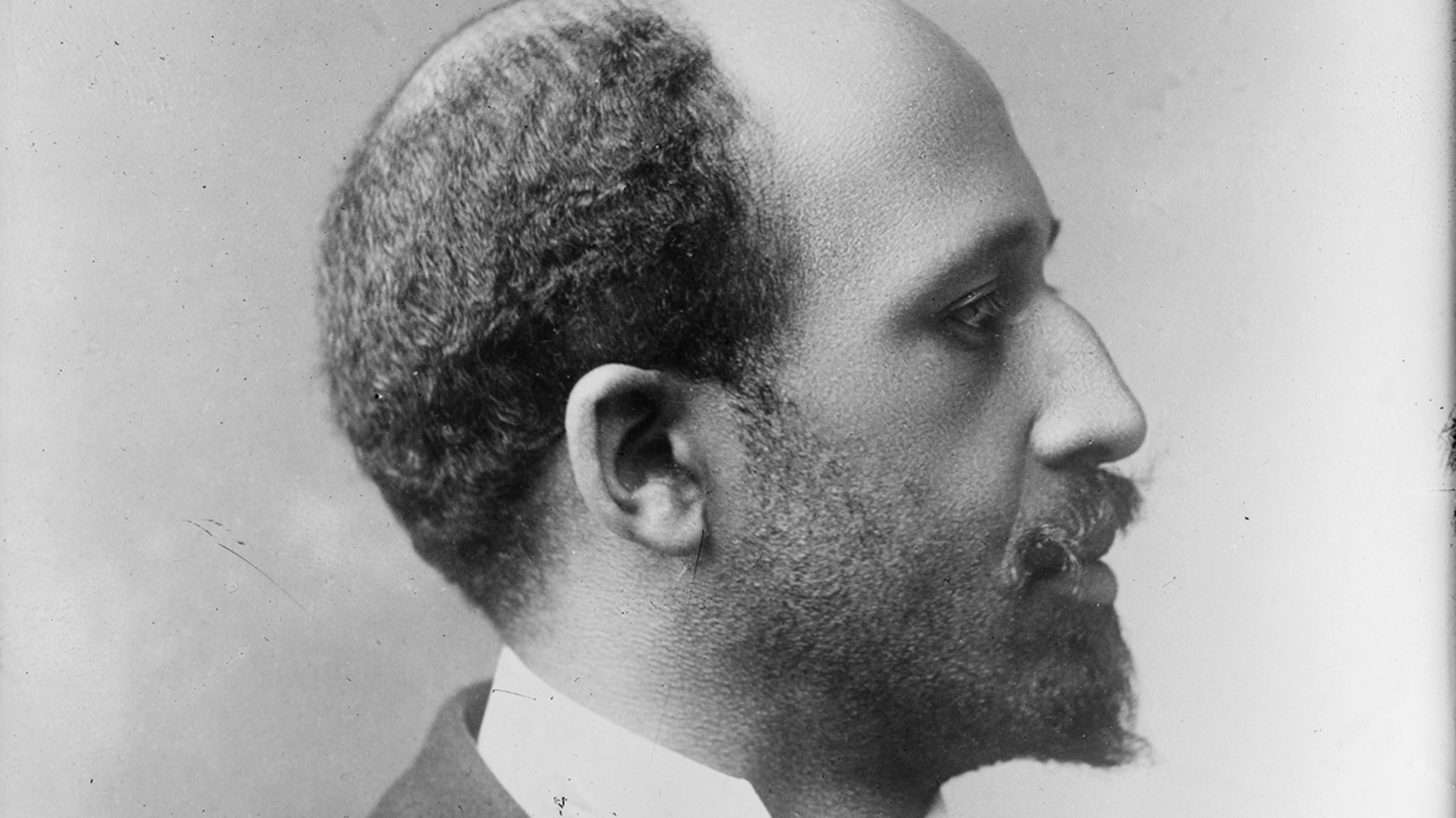

The towering intellect of W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was a cultured writer, political philosopher and activist with enormous intellectual achievements who, over his long life, relentlessly pursued the goal of equality for Africans and African Americans. He wrote influential treatises on Black life, helped establish the discipline of sociology, traveled widely, ran for political office and became a powerful journalist and public speaker.

In 1903, from his office at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta), where he was a professor, he wrote his masterpiece, “The Souls of Black Folk,” giving voice to the central challenges facing Black Americans.

Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes become Bulldogs

Charlayne Hunter (now Charlayne Hunter-Gault) simply wanted to become a journalist. Hamilton Holmes simply wanted to become a doctor. They graduated from Atlanta’s Henry McNeal Turner High School together in 1959 and set their sights on Athens and the state flagship, the University of Georgia.

The school had never had Black students, and they were rejected. Finally, in 1961, a judge ruled that they be allowed to attend.

It wasn’t easy.

On Jan. 9, 1961, the day they arrived on campus, thousands of white people rioted, setting fires outside of Hunter-Gault’s dormitory, hurling rocks inside and yelling racist epithets.

“The town police threw around tear gas, ostensibly to disperse an already-thinning crowd. By the time the state troopers arrived, the protesters were long gone,” Charlayne Hunter-Gault wrote, adding that the school briefly suspended her “for, they said, my own safety.”

How COVID-19 exposed the Black community’s long history of housing instability

Housing insecurity is not a new problem for Black America. Jim Crow-era discrimination and low wages often made it difficult for African Americans to keep roofs over their heads, and redlining made it tough to buy, issues that federal laws would later try to correct with debatable success.

But the coronavirus pandemic served as one of the greatest threats to Black housing stability, as families struggled to avoid being unhoused.

Black people are less likely than white people to own their homes — the Census Bureau puts the number at 47% in 2020, during the pandemic, compared to white Americans at 76%. Yet, Black people made up 35% of those evicted nationally since the pandemic began.

“It was already falling apart for lots of people before this,” said Daniel Pasciuti, an assistant professor of sociology at Georgia State University. “With COVID and people losing their jobs and businesses cutting back hours, now we’re just watching the whole process on steroids.”

How an interfaith friendship between Black people and Jews bolstered the fight for Civil Rights

Cooperation between Atlanta’s Black and Jewish communities — spearheaded by the friendship between Martin Luther King Jr and Rabbi Jacob Rothschild — had a major impact throughout the Civil Rights Movement. While King and Rothschild’s friendship did not mark the start of Black-Jewish collaboration in Atlanta, it encouraged a search for commonality, laying the groundwork for future partnerships.

In 1964, after King won the Nobel Peace Prize, Rothschild was among those who insisted the city organize an integrated dinner ceremony in his honor.

“Their friendship and unity in the struggle for civil rights for Black people is symbolic of the ways in which Black and Jewish people can connect in efforts to prevent and end blights against humanity,” Bernice King, MLK’s daughter, said of the relationship between her parents and the Rothschilds. “This is an Atlanta story that needs to be revisited more often.”

How the Sanfords’ love broke the color line in Georgia

Betty Byrom met John Sanford one evening in the canteen at the Indiana University grad school dorm. She found him interesting.

“We talked and talked and talked. When we looked around, we were the only people left in the canteen,” she remembers. “At midnight, he walked me home.” They started dating and John asked Betty to marry him.

But it wasn’t that easy. He was a pale Midwesterner and she was a dark-skinned Georgia girl.

Their union in 1971 was historic, as it ended Georgia’s medieval law forbidding marriage between Black and white citizens.

Lo Jelks, a television reporter who was heard but not seen

In 1967, Lorenzo “Lo” Jelks was hired at WSB-TV, becoming the first Black television reporter in Atlanta.

Legendary WSB-TV anchor Monica Pearson, who worked at the station for 37 years, called him “my hero.”

But his transition to television wasn’t easy.

The station initially didn’t show Jelks’ face on the air, fearing a backlash from some white people. Viewers only saw “Lorenzo Jelks reporting” in white letters in the middle of a black screen.

“I didn’t complain about it because I didn’t have any control over it,” Jelks said.

Jelks left the station in 1976. But he opened the doors, as other Atlanta news outlets began hiring Black reporters.

Despite progress, HIV remains disproportionately Black in Georgia

More than 40 years after the first cases of human immunodeficiency virus were reported, HIV still strikes terror in many people, and it has become a critical problem in Georgia’s Black community.

In 2019, though African Americans made up only about 32% of the state’s population, around 71% of the roughly 2,500 Georgians who were newly diagnosed with HIV were Black.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.