Winfred Rembert documented the Jim Crow era with deeply personal paintings

Winfred Rembert became physically ill whenever he painted harrowing scenes from his time growing up during the Jim Crow era in South Georgia. Created on tooled leather, some of his paintings depict the lynchings of fellow Black men. The artist was intimately familiar with such racial violence, as he had narrowly survived a lynch mob attack in 1967 when he was 21.

Revisiting his raw experiences made Rembert cough and throw up. Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, he suffered from vivid nightmares. He kicked so hard in his sleep that he fell out of bed. Eventually, he was hospitalized.

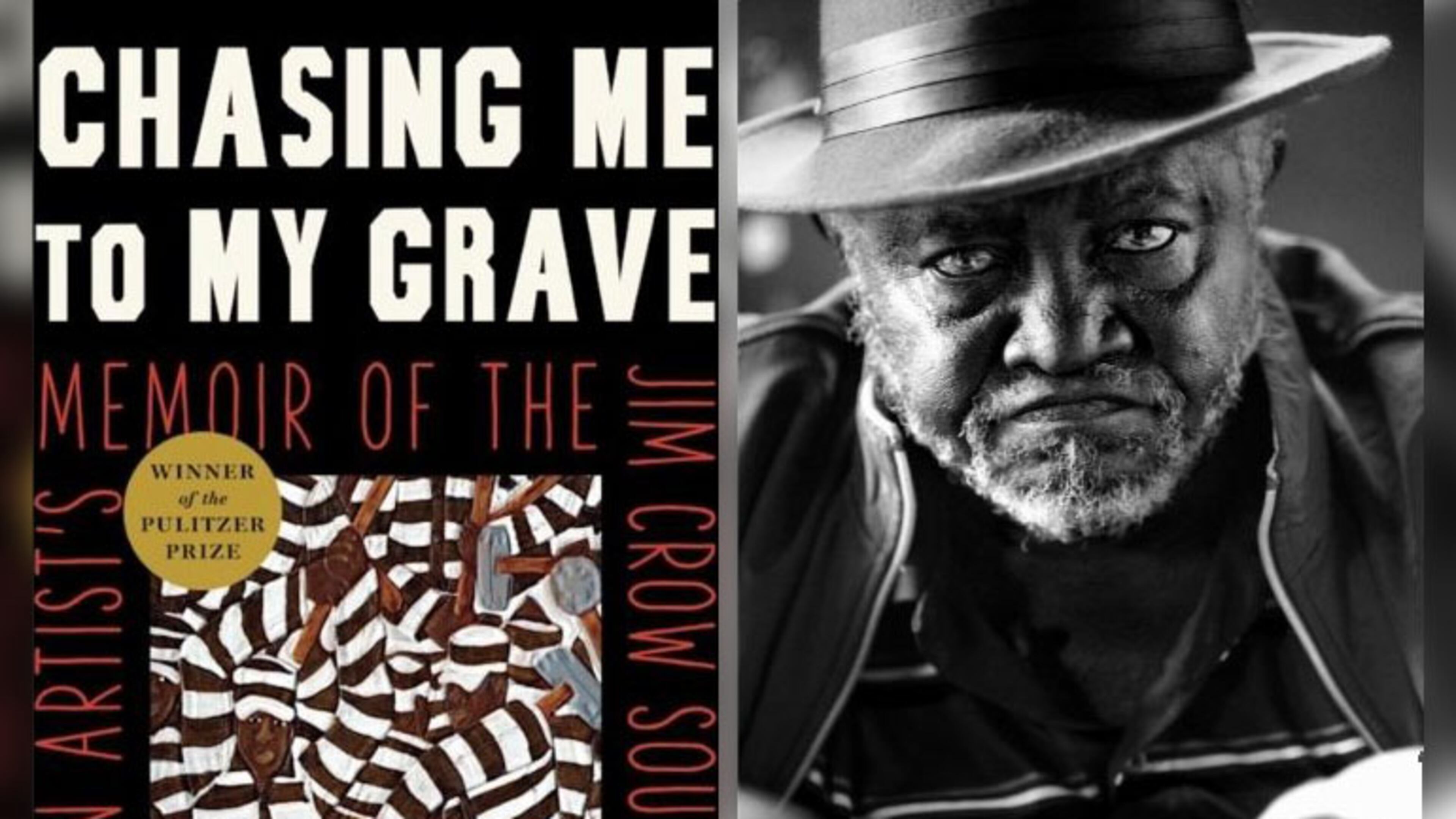

“Sometimes I’d have to stop for a week or so, but then I’d start again,” he said in his acclaimed book, “Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South.” “I wanted to do pictures of what I had experienced, even if it killed me. I wanted people to know what I had been through.”

Rembert died at 75 in 2021, the same year his memoir was published. But his paintings — which are often compared to artwork by Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden — continue to draw widespread attention.

Since 2011, Rembert and his artwork have been featured in two documentaries, “All Me: The Life and Times of Winfred Rembert” and “Ashes to Ashes.”

Three years ago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington announced it had acquired “G.S.P Reidsville,” Rembert’s painting of his experience toiling on a Georgia chain gang. The museum describes the painting as “a work of mesmerizing complexity.”

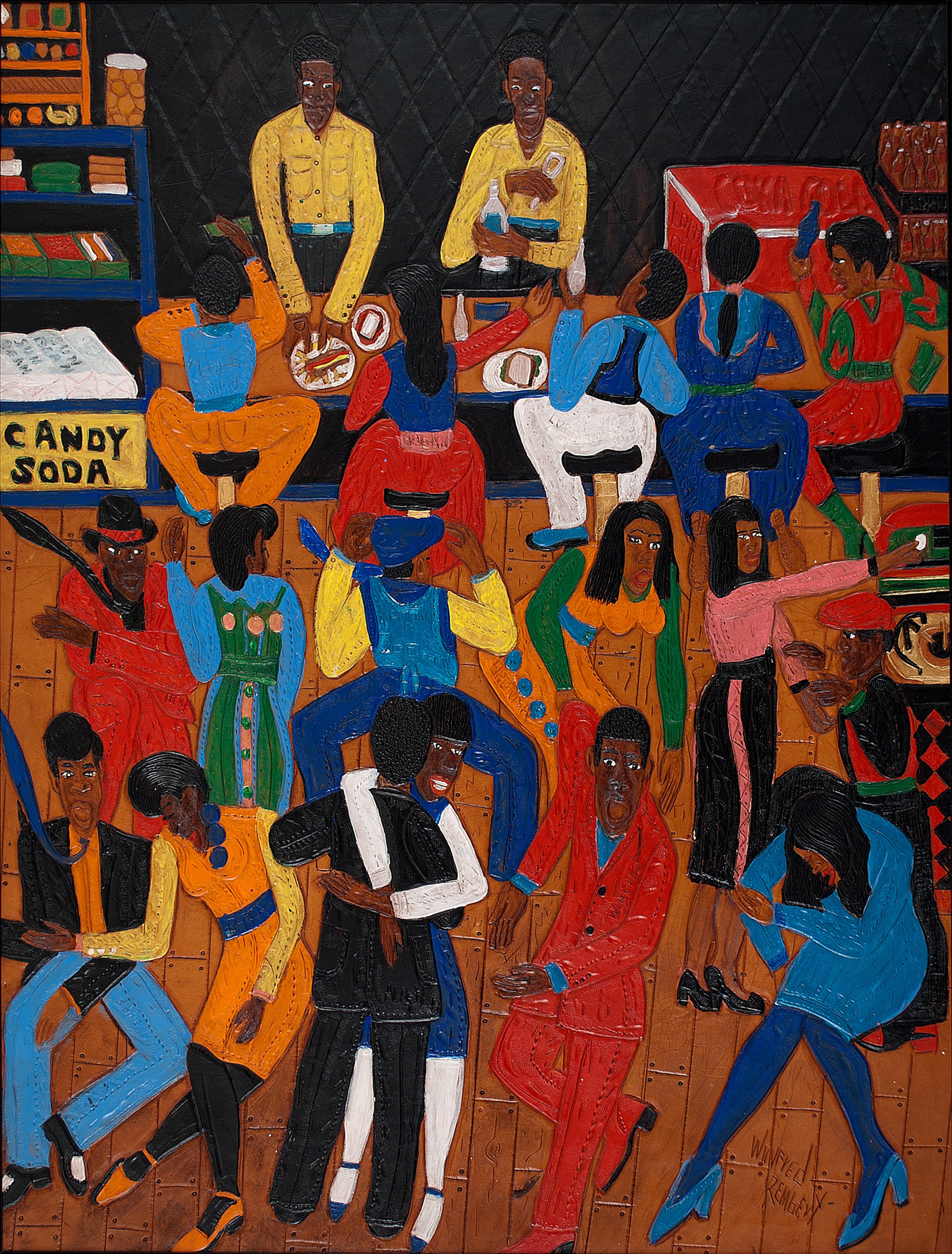

Today, Rembert’s painting of a lively scene inside a juke joint in his hometown of Cuthbert, “The Dirty Spoon Café,” is on display in the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The museum says Rembert carved all the details in leather, even the partyers’ buttonholes, pinstripes and strands of hair.

This spring, his paintings will be the focus of a show at a gallery in Connecticut. Meanwhile, his oldest child, Winfred Rembert Jr., is considering scripts for a feature-length film about his father.

Life in Cuthbert

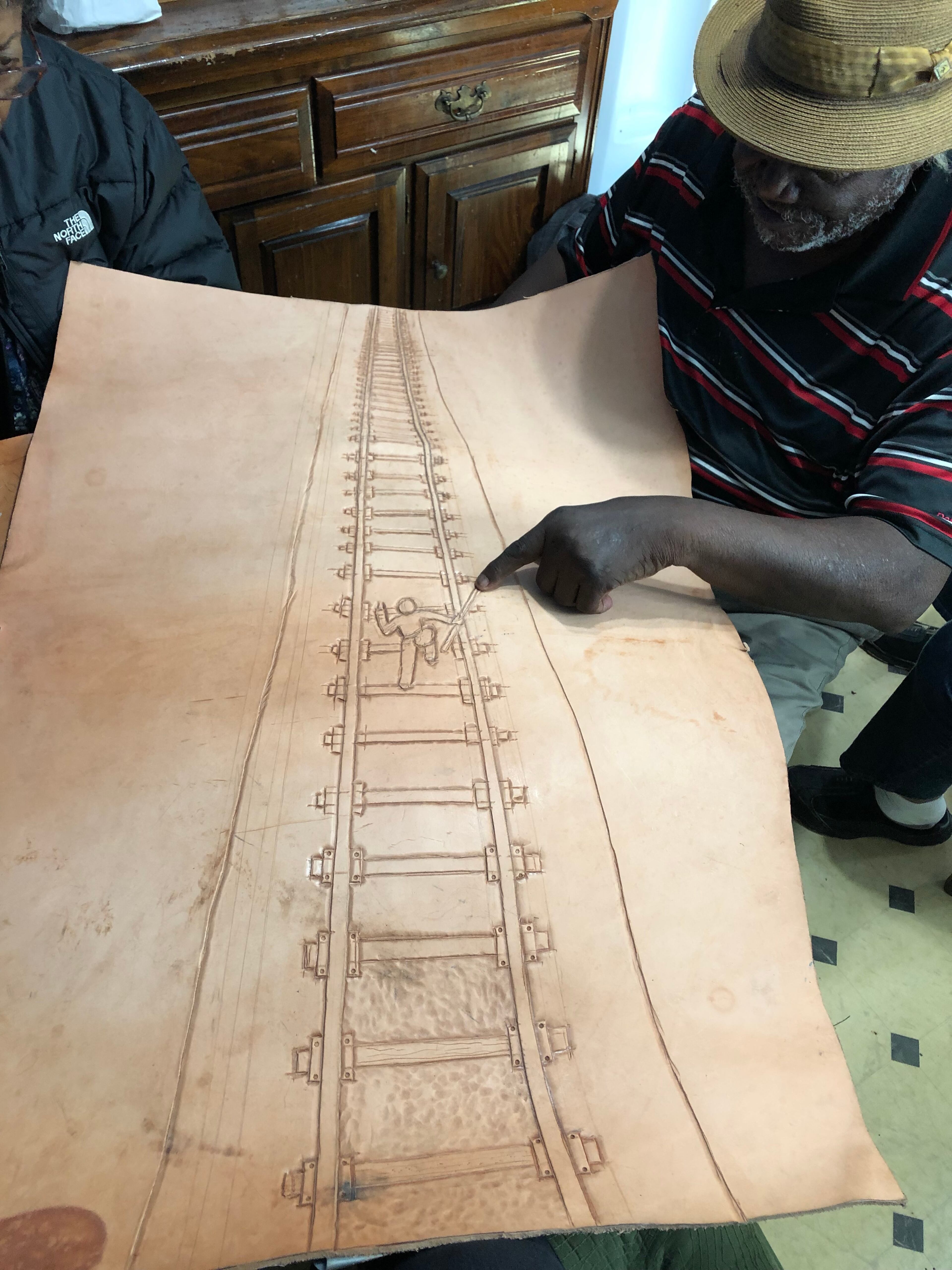

In his memoir, Winfred Rembert wrote about his loneliness growing up in Cuthbert, a tiny community in South Georgia. When he was 3 months old, Rembert’s mother asked a relative to take over raising him. He painted a picture of that scene. In “The Beginning,” his great-aunt, Lillian Rembert, reaches out to accept him from his mother. He also illustrated a heartbreaking image of himself as a boy walking along railroad tracks in search of his biological mother, Nancy Mae Johnson.

Other paintings depict his great-aunt picking cotton. When he was old enough, Rembert joined her working in the fields. He missed a lot of schooling and fell far behind, so he busied himself in class by drawing.

A friend introduced Rembert to a bustling part of Cuthbert on Hamilton Avenue, where Black entrepreneurs operated cafés and juke joints and sold moonshine. Rembert danced and played pool there, later writing about the eccentric characters he met. Rembert’s vivid paintings of those people and places are joyous, even celebratory.

Rembert also wrote about the discrimination, humiliation and violence he and other Black people faced in Cuthbert. The city, he said, featured a restaurant run by the Ku Klux Klan. He witnessed white policemen mistake his great-aunt’s son for someone else and beat him so severely that they knocked one of his eyes out of its socket.

As a teenager, Rembert joined the civil rights movement and began demonstrating in Americus. White men wielding shotguns began to beat the demonstrators. When Rembert heard a gunshot, he ran down an alley and found a car with the keys left inside. He jumped in and took off.

The police caught him, he wrote, and he was held in jail for more than a year without being informed of any charges. Rebelling, he stuck a roll of paper in his toilet and flushed it, flooding his cell. A sheriff’s deputy responded by kicking him in the face. When the deputy tried to kick him again, Rembert threw him to the floor. As the deputy went for his gun, Rembert managed to take it away from him. He locked the deputy in the cell and fled.

After the police caught Rembert again, a lynch mob seized him, stripped him of his clothes, beat him with ax handles and hung him upside down from a tree. The sheriff’s deputy Rembert had overpowered in the cell stabbed him with a knife, drawing blood and causing excruciating pain. As the deputy prepared to stab Rembert again, another man intervened, telling the mob: “No, we got better ways we can do this. Carry him back to the jail. He gonna die anyway.”

“I don’t think I’m ever going to get over what happened that night,” Rembert wrote. “And some of the memories had to come to me in flashes.”

Judges sentenced Rembert to 27 years in prison for stealing the car, taking the deputy’s gun and escaping. He worked on chain gangs, digging ditches and breaking rocks. Before he was released seven years later, he was punished dozens of times with solitary confinement. That involved being placed in what he called the “sweatbox,” a cramped space where he was forced to crouch in the intense heat and darkness.

Two things happened while Rembert was imprisoned that dramatically altered the course of his life. First, he learned to tool leather from a fellow inmate. Second, Rembert saw Patsy while he was building a road as part of a prison work program. They wrote each other letters when he was behind bars. When he finally got out of prison, they married, moved north and raised a family, eventually settling in New Haven, Connecticut.

Rembert was imprisoned in 1987 on drug-related conspiracy charges before he changed course and began painting. He completed his first painting on carved leather as a gift for a friend in 1997, when he was in his 50s. Winfred Rembert credited his wife, Patsy, with encouraging him to paint. Her husband, she said in a recent interview, “finally got the nerve to talk about it and to write about it, something he had wanted to do for a long time.”

“I want people to know as much as they possibly can about this man, who I thought was so great,” she said, adding that her husband’s deeply personal paintings are a “true account of how we were surviving.”

Rembert is still remembered in Cuthbert, where city officials have discussed honoring the artist in some way, perhaps by naming a street after him.

“We certainly will do something that is fitting and proper for his contributions,” Cuthbert Mayor Bobby Jenkins said. “It is something that is long overdue.”

‘Chasing Me to My Grave’

Years ago, Erin I. Kelly was searching online for artwork by Jacob Lawrence when she stumbled across Winfred Rembert’s paintings. Impressed by their originality, the philosophy professor wanted to learn more. So she watched the “All Me” documentary about him and then reached out to the filmmaker, who put her in touch with Rembert.

Kelly interviewed Rembert in 2015 when she was working on a book about criminal justice. She found him fascinating. Later, Rembert told her he was searching for a writer who could help him write his memoir.

Between 2018 and 2020, the two met twice a month at his home in Connecticut, where she recorded him telling his story. She admired the courage he showed in excavating his traumatic experiences.

“It was difficult for him to confront the memories, but he felt really driven to do it,” said Kelly, who teaches at Tufts University in Massachusetts. “He wanted the truth of what happened to him to be part of the historical record.”

A year after Rembert died, his memoir received the Pulitzer Prize for biography. The judges described it as a searing “account of abuse, endurance, imagination and aesthetic transformation.”

Winfred Rembert’s legacy

Rembert brought a gift with him when he visited the Washington Montessori School in New Preston, Connecticut, 14 years ago. It was one of his detailed drawings of people picking cotton.

Today, students there are studying that drawing and Rembert’s life and are preparing to exhibit their own artwork inspired by his paintings this spring. Art collectors are planning to enter their Rembert pieces in the show. Opening night at the Washington Art Association and Gallery in Connecticut is set for April 28.

Winfred Rembert Jr. is gratified his dad continues to draw such attention. He remembers him as a devoted father and a generous and endearing artist who didn’t want anyone to be left out of anything. His dad, he added, was his hero.

“Throughout his whole life, he was trying to get himself known. And now classrooms are dedicating artwork for him. Schools are going out of their way to showcase him,” said Winfred Rembert Jr., also an artist who lives in Hamden, Connecticut.

“He took the worst of what happened to him and was able to make the best of it. He was able to make a family out of it. He was able to meet his wife from it. He was able to make a career out of something that happened to him.”

The father of six children, Winfred Rembert Jr. said his first grandson is due in May. The baby will be named Azriel Winfred Rembert.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This year’s AJC Black History Month series, marking its 10th year, focuses on the role African Americans played in building Atlanta and the overwhelming influence that has had on American culture. These daily offerings appear throughout February in the paper and on AJC.com and AJC.com/news/atlanta-black-history.

Become a member of UATL for more stories like this in our free newsletter and other membership benefits.

Follow UATL on Facebook, on X, TikTok and Instagram.