Treasure hunters become embroiled in political coup in ‘Devil Makes Three’

“Treasure is trouble,” says Matt Amaker, co-owner of ScubaRave, one of Haiti’s few professionally certified diving businesses. Having once worked on a salvage boat, Matt is familiar with the delusions of gold fever big-talk: “a minute into the conversation and you’re suddenly richer than the Walmart guy.”

Not that it matters, because, for the moment, Matt is a perfectly content “blan” — a white foreigner — chasing an honest buck. He enjoys Haiti’s social life, hanging out with his buddy and business partner Alix Variel, whose droll, worldly family has survived for generations as members of the country’s “land rich, cash poor” elite.

Everything’s indisputably going great. The only problem is that it’s 1991, and a year of living suddenly arrives with a military coup d’état ousting Haiti’s first democratically elected leader, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

With the nation drifting into chaos, Matt lays up at the crumbling Variel estate, mending the broken ribs he’s received courtesy of the “Anti-Gang” police who’ve seized ScubaRave’s old jetty for their seaside dope drop. He’d like nothing better than to be an apolitical, happy-go-lucky American player, but he discovers the hard way that, in Haiti, there’s no such thing as “in-between.”

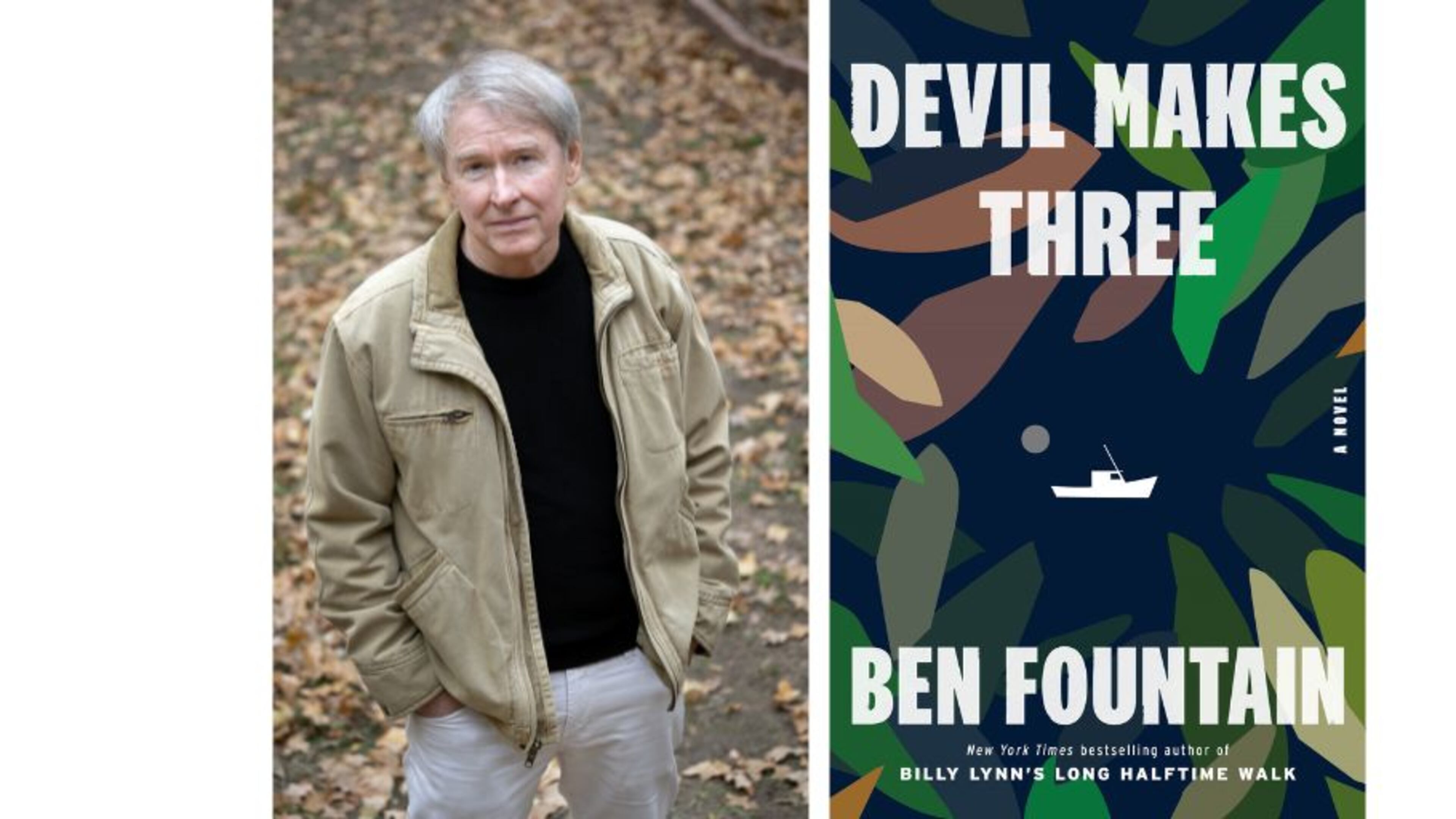

Wherefore, we have Ben Fountain’s “Devil Makes Three,” a confident masterpiece of tropical romance, high adventure and smart political intrigue, set to muted vodou (voodoo) drums and passionate Kreyol (creole) whispers.

Haiti is a former French slave colony with a deeply troubled history. Fountain probes the country’s complex social and political culture through figures of contrary purpose: Audrey O’Donnell, a sharp, Machiavellian CIA operative, and Misha Variel, Alix’s brilliant, radical sister.

To Audrey, “Haiti’s best hope … (is) to integrate into the global economy.” Like all spies, she embraces “deceit in the service of high purpose,” and, accordingly, accepts the agency’s collusion in drug deals involving the Haitian armed forces.

At odds with her arrogant CIA colleagues, Audrey is determined to learn more about “Planet Haiti” through its dominant belief system, vodou. Her shaman/mentor explains vodou as a “service to … the spirits and the dead” that breathes life into the people. “With Vodou you keep your personality no matter who’s attacking you.”

Misha is a 21-year-old scholar of Black Atlantic studies at Brown University, where petty intellectual squabbles are at a remove from the harsh realities of poverty and disease she faces upon her return to Haiti.

With no medical experience, she references her academic training — Foucault and Adorno — to make sense of her daily struggles working at the desperate clinics run by the physician Jean-Hubert, one of Fountain’s marvelous secondary characters.

The relationship between Audrey and Misha furnishes “Devil Makes Three” with cerebral conflict. Yet, with Audrey falling in love with Alix, and Misha with Matt, the women create a shaky rapprochement, intent on saving the two men from their reckless adventurism.

They can’t, of course, because treasure is trouble in the form of bronze cannons, astronomically valuable, that Matt and Alix plan to “float up” from a sunken Galleon using a deck crane mounted on a “transoceanic liner.” The technicalities of the operation and the actual endeavor energize “Devil Makes Three” and steady its loftier philosophical aims.

Inevitably, soldiers arrest Matt and Alix on serious charges that include “conspiracy to commit terrorism.” On a working prison furlough granted by Haiti’s top general, an amateur scuba enthusiast, Matt becomes ensnarled in a ridiculous diving project to locate Columbus’ long-vanished ship, the Santa Maria, in anticipation of the quincentenary of his 1492 landing.

All of this offers the comic relief of an early Woody Allen comedy, but with Alix wasting away in prison, “Devil Makes Three” becomes a race against the clock, its suspenseful climax boosted by the story’s slow-motion escape velocity.

In the Caribbean swirl of Fountain’s kaleidoscope, Haiti’s colorful urban scene and diverse topography are enhanced by Fountain’s amusing metaphors that, synchronously, carry deep feeling. Port-au-Prince, the sprawling capital, has “a dull orange haze hanging over everything like a fulminating cloud of Cheetos dust.” In the countryside, “Herons stood in the irrigation ditches, still as golfers crouching over a money putt.” Under the sea near ScubaRave, an outsize elephant ear floats into view, “a billowing membrane situated at the edge of a shelf, swaying like a choir singing a slow and mournful dirge.”

Ben Fountain is a Texas-based writer who grew up in North Carolina. He has a loving commitment to Haiti, having visited many times. His debut novel, “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” about a reluctant Iraq war hero, became a 2012 National Book Award finalist, subsequently adapted for film by director Ang Lee.

A dogged literary journalist, Fountain covered the Clinton-Trump presidential campaign in “Beautiful Country Burn Again” (2018), so he’s no stranger to confronting volatile situations and evaluating political issues from opposing sides.

The author has done both here. Though “Devil Makes Three” attains a new level: a 500-plus-page book, it is not a work of modest ambition; its only flaw may be that it’s not longer.

Yes, we’d like to know what might happen to Matt Amaker and the Variel family during, say, the cataclysmic 2010 earthquake or in the terrifying gangland takeover of recent years. (Just this month, the U.N. Security Council has voted to deploy an armed multinational force to Haiti.)

Further, “Devil Makes Three” leaves us pondering the possibilities of an alternate Haitian future, when France lives up to its claims of “civilization” and finally pays the tens of billions in reparations that it owes to this poor and mystical land.

FICTION

“Devil Makes Three”

by Ben Fountain

Flatiron Books

544 pages, $30.99