The fight to keep jazz alive in Atlanta

Joe Gransden’s band takes the stage for its weekly jam session one Wednesday night at Venkman’s in Old Fourth Ward. The crowd fills up as musicians improv over Thelonious Monk and Duke Ellington standards. The audience roars after each solo, trumpets wailing and drums keeping the beat, all seamlessly transitioning into the next melodic line. Jamison Chandler, a trumpeter and jazz educator visiting from New York, plays just like the old days when he was first learning his craft in Atlanta decades ago.

For many of these musicians, this is one of just a handful of venues left in Atlanta to play jazz for large audiences. Populated with dozens of jazz clubs and venues in the 1950s and 1960s, Atlanta’s jazz scene has dwindled in recent years as interest in the musical genre has waned. Some of the remaining jazz-specific venues closed shortly before and during the pandemic.

Among the audience at Venkman’s are Edwin and Janice Williams of Conyers. He’s a Berklee College of Music graduate who played upright bass with the John Robertson Trio for decades at Dante’s Down the Hatch. She’s a former jazz singer. They believe the jazz scene in Atlanta is primed for resuscitation. To that end, the Williams founded the nonprofit Jazz Matters to celebrate the history and promote the future of the genre.

For seven years, Jazz Matters has hosted an outdoor concert series at The Wren’s Nest. This year features performances by Barry Richman, Louahn Lowe and Marla Feeney on Aug. 19; Dan Wilson, Marcus Williams and Jennifer Farnsworth perform Sept. 16.

The organization also promotes jazz through community events and outreach programs for seniors. And it mentors up-and-coming artists and educates them on different eras and forms of jazz like the Harlem Renaissance and Afro-Cuban jazz.

“There’s a lot of learning that happens with (young artists) just being in the presence of seasoned artists, and also seasoned artists learn from younger artists. That interchange of wisdom, it’s all happening over conversations about something they all love,” said Janice before the jam session at Venkman’s.

The education component of Jazz Matters is just as vital as the concerts because school systems have eliminated music programs, “which was an excellent feeder for jazz,” said Janice. “We can’t keep the art form alive unless there’s some young people in the pipeline coming through.”

Chandler echoes that sentiment. Back in the day, he said, “you had older musicians taking you under your wing like an apprenticeship, and that doesn’t really exist today.”

Preserving the genre’s history is also essential. There was a time when jazz clubs in Atlanta were open into the late hours of the night and musicians could jam any day of the week, said Edwin. He believes keeping that history alive is the key to making jazz matter more in Atlanta.

Atlanta’s rich jazz history

Ticket stubs to a 1947 Duke Ellington and Earl Hines concert and a 1937 show with Ella Fitzgerald and Chick Webb are among the thousands of mementos from Atlanta’s jazz past that James Patterson, 86, has collected in his lifetime.

Associate professor of music and director of jazz studies at Clark Atlanta University, Patterson is one of the few remaining jazz greats who can still remember the Atlanta jazz scene from the 1950s and ‘60s. The jazz flutist studied at Clark with Wayman Carver and since 1968 has led the university’s jazz orchestra, which has played with greats such as Dizzy Gillespie, Jimmy Heath, James Moody, Wynton Marsalis and Ellis Marsalis.

“Jazz was so connected to Atlanta’s growth and the civil rights movement,” said Patterson. “The scene was as rich as New York or Chicago.”

Among the early jazz greats who got their start in Atlanta was Fletcher Henderson. The pianist, composer and bandleader was one of the most prolific jazz arrangers who helped pioneer big band and swing jazz.

Many of those who shaped the genre trained at Clark College, including pianist Duke Pearson, who recorded with hard bop saxophonist Cannonball Adderley and trumpeter Donald Byrd, and would later influence pianist Herbie Hancock. Pearson composed standards like “Jeannine” and worked with jazz record label Blue Note while collaborating with Atlanta’s jazz pioneers.

Musicians played venues such as the Magnolia Ballroom, the Waluhaje and the Top Hat Club, where Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong performed. When the latter club closed in 1949, it reopened as The Royal Peacock, hosting performances by Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and James Brown.

The Royal Peacock also served as a meeting place for civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King, Jr., Andrew Young and Hosea Williams. As did Paschal’s La Carousel, which was the only nightclub in Atlanta that welcomed Black, white and LGBTQ musicians when it opened in 1960.

Saxophonist Joseph Jennings, former director of the Spelman College Jazz Ensemble, said the Atlanta jazz community helped integrate the city by bringing together white and Black musicians. He recalled that when he arrived from Illinois in 1970, some clubs in Buckhead didn’t allow a Black musician to perform without a white musician present.

“The clubs broke that down eventually, but that was the way it was,” Jennings said.

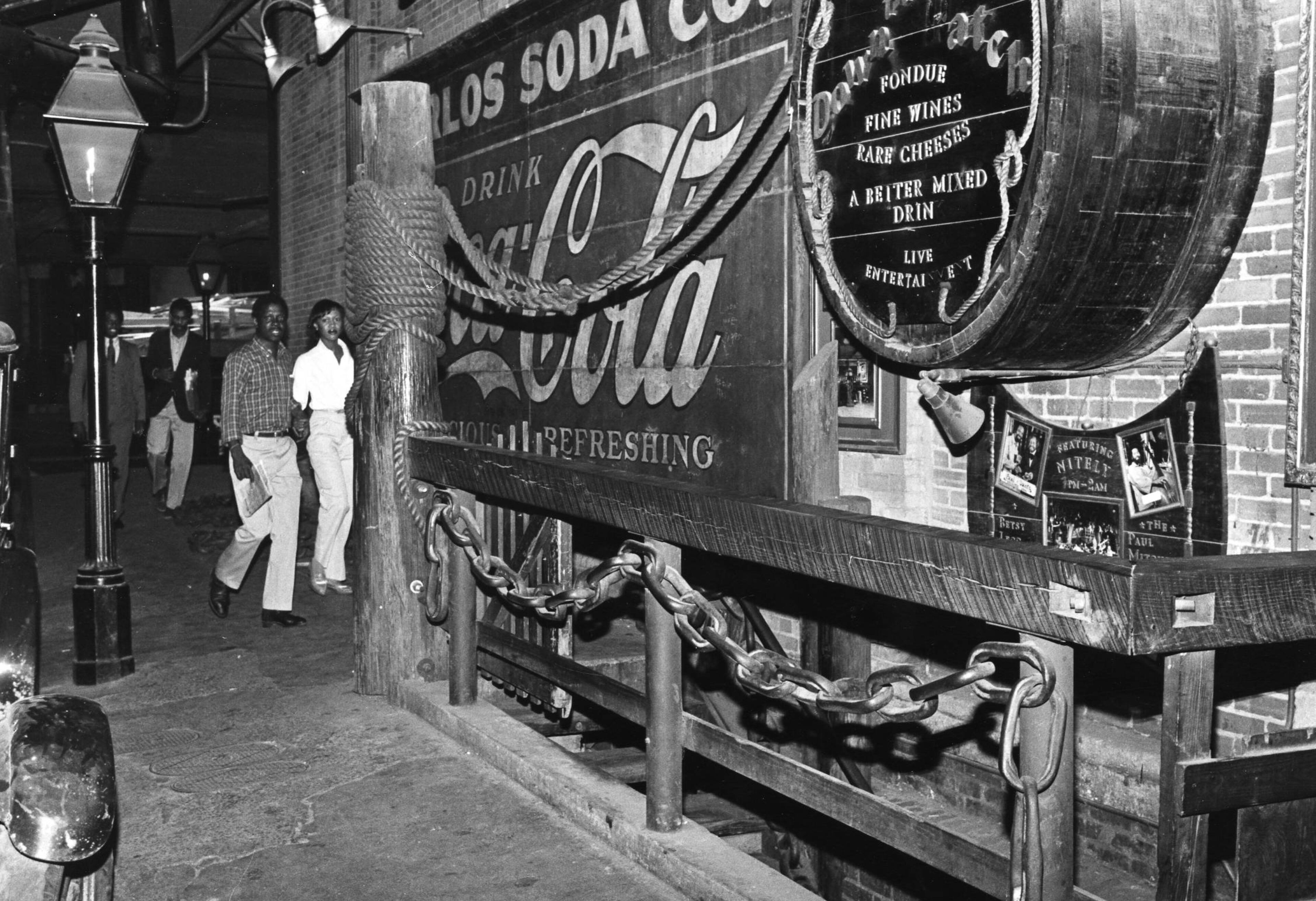

Musicians of all races, though, played in Underground Atlanta, which, beginning in 1969, became a hot spot for jazz in the city thanks to clubs like The 12th Gate and Dante’s Down the Hatch before it moved to Buckhead in 1981.

“Dante’s for me was like a laboratory,” said Edwin Williams, who played there for 23 years. “It was a refining station where you could sharpen yourself up. Six nights a week, five sets a night for that length of time, you got chops, that’s all there is to it.”

In addition to the clubs, Atlanta has a rich history in jazz festivals. Jennings, who formed the jazz ensemble Life Force with fellow saxophonist Howard Nicholson and taught saxophonist Sherman Irby, helped assemble a festival at Mozley Park in the 1970s. He said it was a precursor to the Atlanta Jazz Festival, which began in 1978 and continues to this day. Among the artists who have performed are Lionel Hampton, Wynton Marsalis, Nina Simone and Herbie Hancock.

During the 1980s and 1990s, a variety of factors including rapid construction and changes in musical taste led many long-time clubs to close, including nearly all of Atlanta’s ‘60s-era jazz clubs.

But then a ray of hope appeared. Churchill Grounds opened in 1997 next to the Fox Theater featuring jam sessions led by trumpeter Danny Harper and his wife, vocalist Terry Harper. With its location on Peachtree Street in the heart of Midtown, the club became the city’s premier jazz spot.

Joe Gransden, the trumpeter, vocalist and big band leader who is one of Atlanta’s most prominent contemporary jazz musicians, developed his chops at Churchill Grounds. When the club closed in 2016, the community was shook.

“When that ended, we were all standing around and asking, ‘What are we supposed to do? Where were we going to see each other? Where we were going to hang?’” Gransden recalled.

It was a struggle for musicians to find a place to play. Some played jazz with Atlanta’s African American Philharmonic Orchestra. Gransden found venues across the metro area to play one night here, one night there.

Cafe 290 in Sandy Springs was still going, but the pandemic finally shut it down.

Things looked grim for jazz in Atlanta.

Atlanta jazz today

Laura Heery, an Atlanta architect, moves to the music of the Wednesday night jazz jam at Venkman’s. Her grandfather played stride piano, she said, and she has fond memories of her mother taking her to see guitarist Wes Montgomery at the Atlanta Jazz Festival when she was a child. What she calls “common denominator music” floods her with decades of memories.

“There’s something about the history and the way jazz touches me that affects a lot of us, so when everything’s so new, it lets us touch back to a different era,” she said.

Gransden said Venkman’s has been instrumental in keeping jazz alive in Atlanta. Trumpeter Terence Harper, whose parents were the house band at Churchill Grounds, agrees.

“Venues like this mean the world to the music scene, giving us a place to continue to play and grow as musicians and get a chance to not only hone in on our skills and our craft but also get a chance to meet other musicians and collaborate with other people,” said Harper.

And Venkman’s isn’t alone. Jazz jams also occur at TEN ATL in East Atlanta Village, Red Light Cafe in Midtown and St. James Live in south Fulton.

The jazz scene has a long way to go to recover some of its past glory, but Gransden is hopeful. All it takes is a few more clubs opening and a little more programming.

Michael Cruse, an Atlanta-based trumpeter who trained in New York and Chicago, agrees. Cruse teaches at Emory University, does outreach to Atlanta Public Schools and plays with different ensembles across Atlanta.

“We’re going to make it happen anyways, no matter what obstacles are set in front of us,” he said. “It’s really a testament to how focused and driven the scene is about the community. Just because we don’t have one place that’s the home, it’s spread out throughout the city and it’s giving more opportunities to everybody, not just a few people.”

It all comes back to Edwin Williams’ mission with Jazz Matters to embrace the history of the genre and to share knowledge with the next generation.

“The greatest legacy that you can leave behind is the knowledge that you impart on somebody else, and this music will be alive forever because of one’s ability to teach,” Harper said.

“Hopefully that person becomes an incredible musician and performer but also teaches to preserve the history of the music.”

EVENT PREVIEW

Jazz Matters concert series. 7:30 p.m. Aug. 19 and Sept. 16. $30 lawn, $400 table for 10. The Wren’s Nest, 1050 Ralph David Abernathy Blvd. 404-474-1211. yesjazzmatters.org

Joe Gransden’s Jazz Jam. 7 p.m. Wednesdays. Free. Venkman’s, 740 Ralph McGill Blvd. NE, Atlanta. venkmans.com