“Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-taught Artist in America” at the High Museum of Art is centered on an extremely interesting premise that may surprise even fans of self-taught art.

After World War I, self-taught artists were able to infiltrate the rarefied world of museum culture in surprising ways, often more successfully than their educated artist peers. They were able in that way, the exhibition proposes, to expand the definition of what an American artist was.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

High curator of folk and self-taught art Katherine Jentleson notes that the first black artist (William Edmondson) and the first female painter (Josephine Joy) to have solo shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York were both self-taught. In the 1920s and ‘30s, institutions like MoMA, but also art critics and collectors, were remarkably receptive to their work, which bucks common understanding of the gatekeeping and hierarchies that existed at institutions like MoMA.

It’s hard to argue with that sense of boundary-pushing in terms of style and theme when contemplating the work collected in “Gatecrashers.”

A case in point: housepainter John Kane’s mesmerizingly uncanny painting of two Scottish dancers “Scene From the Scottish Highlands” (circa 1927). Two young boys with porcelain doll-like faces and stubby bodies are frozen mid-jig in front of what looks like a theatrical, two-dimensional backdrop of fields and sky. The modernist interest in flattened space that challenged classical painting’s adherence to realism was of great interest to traditional artists at the time who often advocated for the novelty of work like Kane’s. In fact many self-taught artists of the time found their staunchest defenders in traditional artists like painter Andrew Dasburg, who as a juror demanded that Kane’s work be included in Pittsburgh’s 1927 Carnegie International, and Hale Woodruff, who included the self-taught artist Horace Pippin in his “Art of the Negro Muses” mural at Clark Atlanta University.

The work on view can often feel shockingly contemporary, like Lawrence Lebduska’s “Untitled (Horses and Snakes)” (1936), a trippy fantasia of rose, blue and cantaloupe-colored ponies frolicking against a foamy cotton candy sky and hillsides like chunks of red velvet cake.

Far from the ostracized outsiders they are often reduced to, “Gatescrashers” argues that many attended museum and gallery shows and were aware of — and often inspired by — European painting, incorporating its techniques and themes into their own work.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

An admirer of Paul Cezanne, Black artist Horace Pippin returned from World War I to racism at home and managed to paint despite a war injury. Works like his haunting 1933 painting “The Buffalo Hunt” are on view in “Gatecrashers.” In this stark portrait of a lone hunter stalking a pair of buffalo, the buffalo and the hunter become abstractions in the play of white snow and black figures.

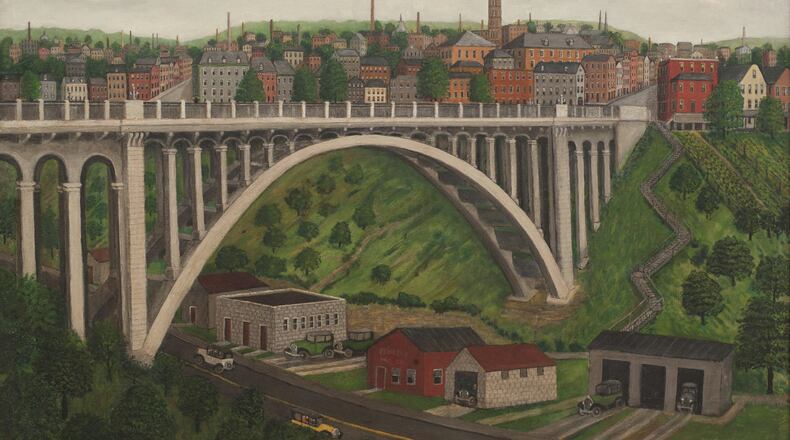

In many ways these artists were representatives of America’s unique melting pot and belief in self-reliance and grit. Ukrainian, Greek, German and Scottish immigrants, featherweight boxers, truck drivers, brickyard workers and house painters, they offered up idealized visions of farm life in work like “Sugaring Off” (1943) from Grandma Moses, or the great spewing factories of Pittsburgh that transfixed John Kane.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

“Gatecrashers” is divided into seven sub-themes and often references related works in the High’s collection not on view here. For that reason the exhibition can sometimes suffer from an overabundance of ideas that can occasionally distract from the subtler gifts of the work itself. But ultimately, it’s hard not to admire the egalitarian spirit of the show. “Gatecrashers” feels like a humanizing gesture, giving these artists agency and a definitive role in art of the time.

ART REVIEW

“Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-taught Artist in America”

Through Dec. 11. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Satudays; noon-5 p.m. Sundays. $16.50 for timed tickets; free for members and children under age 6. High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St., N.E., Atlanta. 404-733-4400, www.high.org.

Bottom line: Rich artist backstories and a new take on art history balance what can feel like an overload of themes and ideas.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured