Commerce and radical politics find a common ally in the Modernist poster in “Disrupting Design: Modern Posters, 1900-1940,” on view at the High Museum of Art through April 24. The exhibition brings together just under 50 posters and includes a lot of heavy hitters from design history from the collection of Merrill C. Berman.

Clean, sans serif title text curves across the gallery floor, echoing a grid-breaking poster from 1928 by Max Burchartz later in the show. It’s a smart curatorial gesture that echoes the New Typography, an ideology that emerged out of the German Bauhaus School. It was codified in German designer Jan Tschichold’s 1928 book “Die Neue Typographie” (”The New Typography”), which advocated for clear, asymmetrical and dynamic design. In the context of a museum exhibition, floor text defies the expectation that titles belong on the wall, and, perhaps, suggests the humble, oft-ignored place of the poster in visual culture.

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

Entering the galleries, viewers see the roots of later Modernist designs: on the left, Art Nouveau and its kindred movements Jugendstil and the Vienna Secession; on the right, the radically simple designs of Sachplakat (which translates from German to “object poster”).

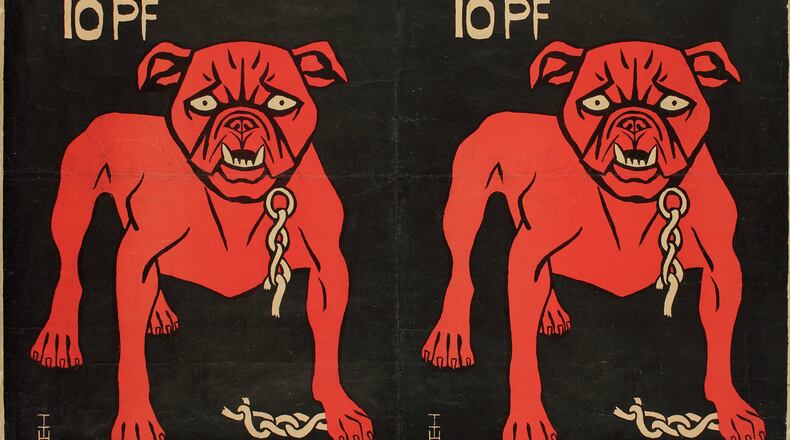

On the Art Nouveau side, Thomas Theodor Heine’s bristling red bulldog for German leftist magazine Simplicissimus stands out amongst its more ornate and flowery peers.

The poster is funny and raw, with woodcut-inspired lines and a stark palette of red, white and black. The expressionism-meets-Jugendstil mascot represents the dissenting voice of the people opposed to Kaiser Wilhelm II. He looks ready to fight, and is, quite literally, off the chain (he prominently sports broken shackles).

Simplicissimus is a prime example of the impact of a single design. As design professor and writer Steven Heller points out, Heine’s tactics have wide-ranging influences — though some of the more notorious miss its radical wit.

For example, Heine’s overtly leftist image inspired an early poster showing Hitler, and the now-obsolete Red Dog beer revives its eponymous character in neutered, commercialized form. Native Georgians might think of the bulldawg, and it’s easy to imagine Heine’s effect even here.

On the opposite wall, Simplicissimus gives way to gentler advertisements by Lucian Bernhard and Hans Rudi Erdt. Though resoundingly apolitical, they carry forward the blunt simplicity of Heine’s design. Each combines a single word and product image — the basic formula of Sachplakat. The cleverest of the four, Erdt’s “Opel,” 1911, conflates a car’s steering wheel with the letter “O.”

Selections from Futurism, Dada and Modernist Soviet propaganda follow, before a thorough examination of a generation shaped by the New Typography. Posters by one of the exhibition’s lynchpin figures, Jan Tschichold, include his well-known, off-kilter “Die Hose” (“The Trousers”), 1927.

The dynamically set sans serif type is elegantly crisp and effective – striking even in a room of Modernist design. Tschichold’s posters are the first in the exhibition to include photography, implementing a technique dubbed “typophoto” by Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy. Though none of his designs are present, Moholy-Nagy’s influence runs throughout the show. The merging of type and photography approaches an uncomfortable zenith in Russian Constructivist El Lissitzky’s iconic, if disconcerting, 1929 poster for the USSR Russische Ausstellung (USSR Russian Exhibition) that shows the faces of two young people merged, the letters “USSR” printed across their conjoined visages.

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

Nearby, Swiss designers Max Bill and Théo Ballmer offer up quieter designs that push Bauhaus and the New Typography to a state of elegant Modernist distillation. They set the stage for the International Typographic Style of the mid-20th century, which most famously produces the ubiquitous typeface Helvetica.

A selection of works by Latvian designer Gustav Klutsis, a peer of the better-known El Lissitzky, encapsulates the tensions underlying Modernism.

A large poster, “The USSR Is the Shock Brigade of the World’s Proletariat,” 1931, shows an optimistic, heroic figure standing atop a stylized globe in the typophoto tradition. Asymmetrical text echoes his implied forward movement. Tragically, and despite his contribution to Soviet propaganda, Klutsis was executed in 1938 due to his ethnicity during Stalin’s horrific “Great Purge.”

Disrupting Design shifts its tone, reaching a closer-to-home finale with a section dedicated to “Selling Ideologies.” It prominently features American WPA artist Lester Beall’s iconic posters for the Rural Electrification Administration of the 1930s. The lessons of Heine and Sachplakat again play out in Beall’s minimal text and pared-down, colorful imagery. They seem fresh and easy after the more complex photomontages that precede them.

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

Credit: Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection

In “Light,” 1937, Beall places an oversized lightbulb next to a silhouetted house. Slanting lines connect the two against a patriotic, red-and-blue background, making evident the practical benefits of bringing electricity into homes. Nearby, British E. McKnight’s Kauffer’s “Power, the Nerve Centre of London’s Underground,” 1930, displays a similar spirit: The subway is presented as an empowering force of progress symbolized by a bold fist. Zigzagging bolts of electricity connect the hand to the text below. Here, the Modernist spirit emerges again as utopian, though Klutsis’ fate haunts me as I approach the exhibition’s end.

“Disrupting Design: Modern Posters, 1900-1940″ is a bit like walking through a few chapters of a canonical graphic design textbook. The show is a resource for those hoping to expand the scope of their understanding of Modernism beyond the more privileged stories of painting, sculpture, and architecture.

Yet, it’s essential to note that it shares the same problems with traditional design histories. It focuses on men, most of whom are white — an issue recent scholars aim to complicate with more inclusive narratives and resources. And, needless to say, these posters reveal the sexism, racism and xenophobia of their era — all of which persist today — as stories like that of Klutsis so painfully evidence.

VISUAL ARTS REVIEW

“Disrupting Design: Modern Posters, 1900-1940″

Through April 24. $16.50. High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St. NE, Atlanta. 404-733-4400, high.org.

Credit: ArtsATL

Credit: ArtsATL

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (www.artsatl.org), is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. Founded in 2009, ArtsATL’s goal is to help build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured