Review: Brandywine Workshop channels the Black diaspora at Hammonds House

Select works from the Brandywine Workshop and Archive in Philadelphia are on display at Hammonds House Museum through June 22 in the exhibition “Sacred Space: Brandywine Workshop and Archives/Espacio sagrado: taller y archivos Brandywine.” It’s a show not to be missed.

Allan L. Edmunds founded the Brandywine Workshop in 1972, inspired by master printmaker Robert Blackburn’s printmaking studio founded in 1948 and Taller Experimental de Gráfica de la Habana in Havana, Cuba. BWA was founded as an artist-run art space committed to global diversity and as a space to make thought-provoking and high-quality work regardless of ethnicity, culture, age or gender. The exhibition at Hammonds House is composed of works primarily made by African American, Indigenous and Afro-Latinx artists.

BWA has collaborated with major artists such as Romare Bearden and Melvin Edwards, as well as a younger generation of artists such as the late Belkis Ayon, Rashid Johnson and more. Now considered one of the country’s most important art institutions, BWA has an international visiting artist residency program, an expanding permanent collection and several satellite collections nationwide, including at the Harvard Art Museum, the Clark Atlanta University Museum and the Wilfredo Lam Contemporary Art Center in Havana.

Abstract expressionist works produced by male artists dominate the first gallery, such as Sam Gilliam’s “(Untitled) Philadelphia” (1987). Yet Ester Hernandez’s lithograph “Indigena” (1996) is an impressive outlier.

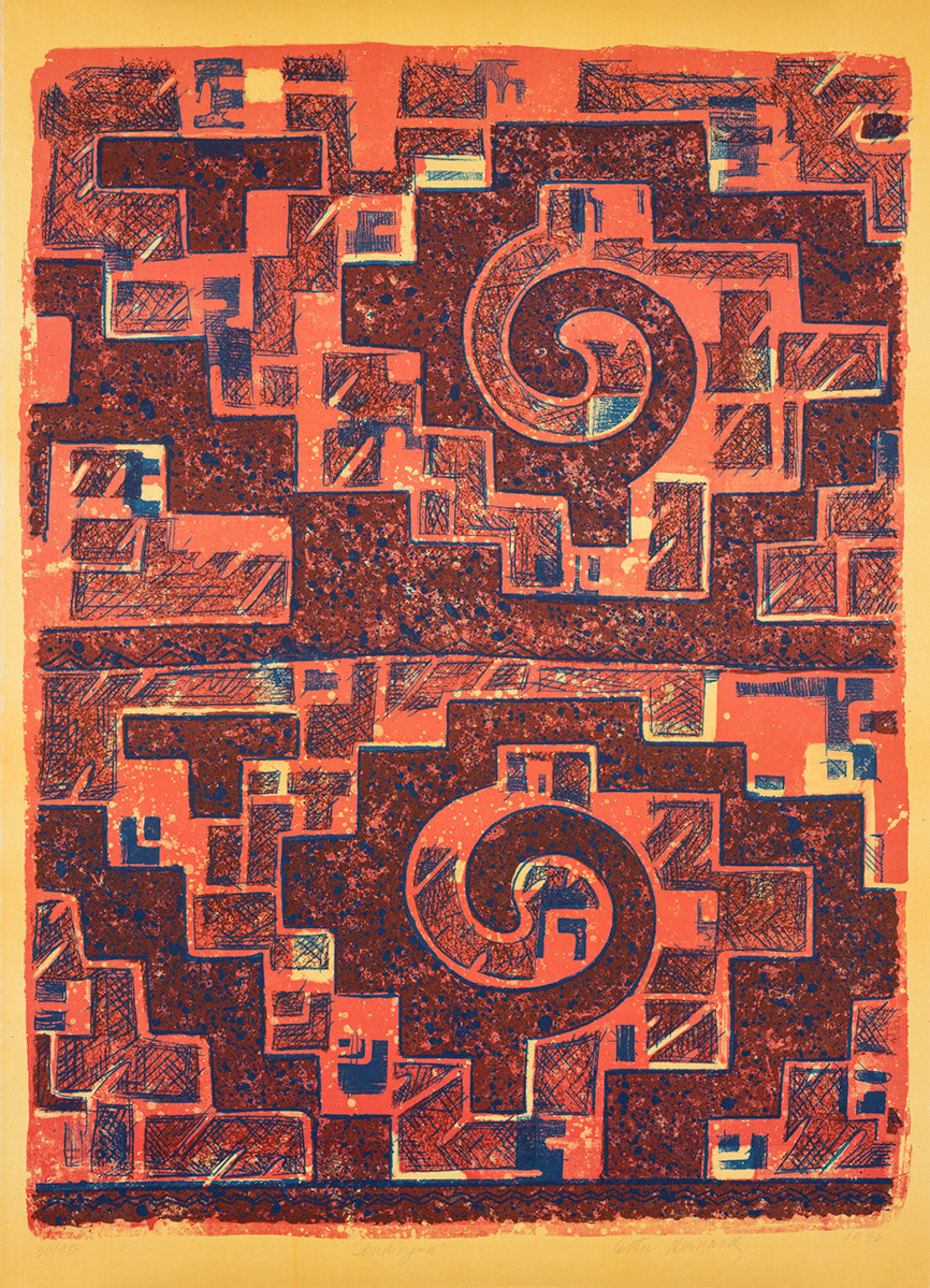

Akin to a modernist grid aesthetic yet reminiscent of intricately woven embroidered textiles, “Indigena” features a monochromatic red motif with irregular geometric forms enhanced by splashes and outlines of cobalt blue. The crosshatched shapes appear etched into and floating against a crimson background. Hernandez’s richly hued palette recalls traditional Aztec textiles that incorporated the red cochineal dye. Hernandez links Indigenous heritage and aesthetics with contemporary printmaking processes and techniques.

Danny Alvarez’s “Untitled (Color)” (2006) immediately drew me in. The multicolored lithograph features a central nude female figure stepping onto an oversized patterned chair, flanked by clawed skeletons that hearken to Dia de los Muertos. Alvarez alludes to her divinity by rendering her orb-like aura expanded with her crown on top. That crown led my vision to a mysterious figure in the background whose crystallized face appeared looming and watching. The figure, according to Alvarez, is the Aztec Earth goddess Tonantzin, whose significance was changed to the Virgin of Guadalupe, then the Virgin Mary. The work is a fascinating graphic narrative, rich in the cultural history of a people and imbued with Mexican cultural and religious iconography.

Several works throughout the show explore personhood, our relationship with nature and how one maintains ancestral spiritual and religious identity.

For example, I fixated on a series of enigmatic works titled “Children of Middle Passage.” Afro-Panamanian artist and scholar Arturo Lindsay memorialized the unknown children who perished at sea during the trans-Atlantic slave trade as intimate scenes of veneration in this series.

In one, titled “Umar of Segou” (2001), Lindsay illustrated an anonymous yet haloed young boy with facial features rendered in thin, symmetric lines with a brilliant, yet vacant gaze that looks out toward the viewer. Lindsay modeled the boy’s body in wide swathes of matte black ink while the curvature of his silhouette, full and voluminous, made the boy appear cloaked in the richest of black velvet, which breaks sharply, lending to the appearance of wings. Below him lies the skeleton of a small maritime vessel.

Yoruba aesthetics and Santeria religious iconography surrounds the boy within an arched frame. This frame alludes to the figure’s sacredness. Here, Lindsay poetically depicts the child’s life force ascending from a velvet chrysalis from the earthly plane to the angelic realm of the spiritual. The work’s visual presence is astonishing. It is resonant of tenderness and innocence and what Lindsay (as someone knowledgeable about Santeria) might call “aṣẹ,” or life force.

“Umar of Segou” and other compelling works such as Janet Taylor Pickett’s color-block print, “Hagar’s Dress,” and Orisegun Bennett-Olomidun’s expressionist work, “Quest: We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest” (1993), feature imagery of the Middle Passage.

Sitting within a niche looking out among several gorgeous prints with flashes of color and light before me, I wondered what a daunting task it must have been to select from Brandywine’s collection. The exhibition’s curator, Halima Taha, undertook a heavy lift, creating a coherent story from so much varied work. “Sacred Space” will spark spirited dialogue and vivid interpretations for many different audiences.

ART REVIEW

“Sacred Space: Brandywine Workshop and Archives/Espacio sagrado: taller y archivos Brandywine”

Through June 22 at Hammonds House Museum. Noon-5 p.m. Thursdays and Sundays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Fridays-Saturdays. Adults, $10; seniors (62 and up), $7; students, $5; free for 12 and under. 503 Peeples St. SW, Atlanta. hammondshouse.org.

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (artsatl.org) is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. ArtsATL, founded in 2009, helps build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.