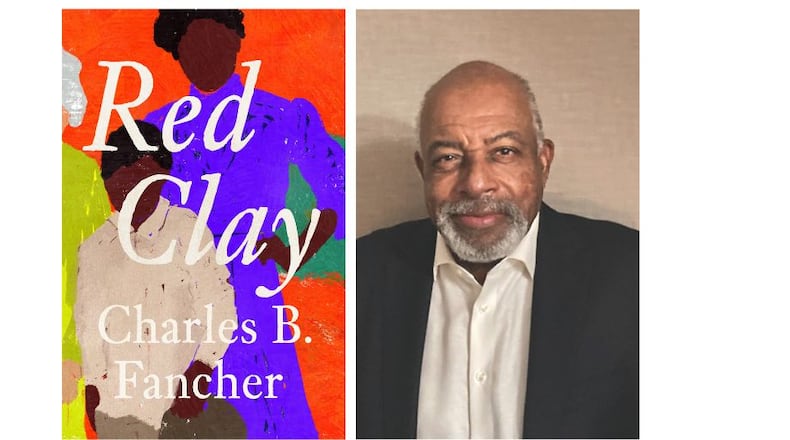

Pennsylvania journalist Charles B. Fancher was born six years after his great-grandfather died and didn’t know much about his ancestor until a few years ago. While visiting his “decorous” 92-year-old mother, Fancher was caught off guard when she started regaling him with wild stories about her grandfather with a “roguish streak” who was born into slavery on an Alabama plantation and proceeded to build a good life for his family in post-Reconstruction South.

Intrigued and encouraged by his mother to write about his grandfather’s life, Fancher consulted with regional historians and dug through online archives. He eventually returned to his family’s ancestral hometown, a place he hadn’t visited since childhood, to interview residents and reconnect with Alabama’s iconic red clay. Fancher details this journey in the afterword of his debut novel “Red Clay,” a powerful and evocative historical family saga that brings the stark reality of transitioning from enslavement to independence in the late 19th century to palpable, vibrant life.

“Red Clay” opens in 1943 with a young woman named Eileen Epps who is home from college for her grandfather Felix Parker’s funeral. She ponders what the lively cast of congregants gathered for his homegoing must have meant to her grandfather. Her grandmother has already died, so Eileen figures her curiosity will go unanswered. But the following day, an elderly white woman who piqued Eileen’s interest at the funeral appears in a fancy car with a request to talk.

The woman introduces herself as Adelaide “Addie” Parker and informs Eileen that “a lifetime ago, my family owned yours.” Eileen is familiar with Addie’s name; the entire family is. As children, Addie would make the enslaved Felix sit behind her every morning at the breakfast table and force him to “eat out of her hand like a dog.” He remained embittered by the humiliation until his dying day.

Eileen is apprehensive but agrees to hear what Addie has to say. As the women converse, Addie fills in some of the gaps in Felix’s story that he never shared with his family and reveals herself to be a complicated, analytical person with a surprising past.

With Eileen and the elderly Addie serving as the novel’s framing device, their storyline recedes into the background and the time frame shifts to the 1860s. Felix and Addie are in their formative years when the South is decimated by the Civil War and Reconstruction begins.

Felix is the only remaining child of Plessant and Elmira, a valet and cook enslaved at Road’s End Plantation on the outskirts of the fictional town of Red Clay, Alabama. Felix’s older siblings were sold by plantation owner John Robert Parker, a man whose conscience tugs him toward the right side of history, even if he lacks the backbone to follow through.

John Robert predicts the South is going to eventually lose the war and concocts a hoax to shield his family from financial ruin when it does. He involves 8-year-old Felix in his deception, much to Plessant and Elmira’s chagrin, but he is ultimately successful and his family maintains control of Road’s End.

John Robert means well and isn’t the worst of his kind. Even Plessant agrees, despite his hostility toward John Robert for selling his older children. At the very least, the Parkers don’t allow their overseers to physically abuse their field workers — most of the time.

But Fancher hardly lets John Robert, or any of his other characters, off the hook. Instead, the author weaves together a cast of complex personalities, each possessing both good and bad qualities, and does a deep dive into how they react to the changing social order spurred by the abolition of slavery. The result is as nuanced as it is engrossing.

In the war’s aftermath, Addie’s egalitarian older brother Claude strings together a calculated system of sharecroppers and land leases, and most of his emancipated slaves stick around. But for a character who starts out promoting fair treatment when his power is absolute, Claude’s loss of authority during Reconstruction reveals more about his moral compass than his privilege ever does. Conversely, while Addie treats Felix poorly as a child, she makes a personal sacrifice in their later years to ensure his safety, which has a tremendous impact on his future.

“Red Clay’s” plot twists and turns as Felix and Addie come of age while Reconstruction transitions into the Jim Crow era. Felix grows into a proud and accomplished man who overcomes a plethora of tribulations on his way to becoming Eileen’s grandfather. Staying alive as a secret band of masked white supremacists known as the “night riders” use whips, guns and bombs to thwart Reconstruction proves a challenge for Felix.

And Addie goes through her own trials as she travels and is exposed to other cultures and ideas that force her to examine her own. Along the way, she develops into a worldly and compassionate woman as the two branches of the Parker family intertwine, grow apart and come back together again many times over the years.

Fancher concludes in the novel’s afterword that at the end of all his research about his great-grandfather, he realized “the forebear in my mind had become something more than just my ancestor. He had become the embodiment of all the Black men, and the women who stood beside them, who clawed their way out of the wretchedness of slavery, who rode the exhilarating wave of Reconstruction, and who navigated the dangers and uncertainty of Jim Crow.”

Full of passion and heart, “Red Clay” brings the best of them to life.

FICTION

“Red Clay”

by Charles B. Fancher

Blackstone

336 pages, $28.99

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured