“Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe” an exquisite undertaking

Who is Nellie Mae Rowe? Self-taught, visionary, folk artist. A true Georgia treasure known throughout the world. A woman with passion and conviction who chose to spread her message through visual channels. An artist who like so many others, in order to survive, had to wait before she could create, only to realize that the lifeblood of survival was through creativity.

Rowe was one of the first to “be a part of the change” and frequently included this kind of messaging in her work, literally and symbolically. She, along with her great friend, benefactor and gallery dealer (there was no such thing as a gallerist back then) Judith Alexander were absolute precursors to Black Lives Matter in the late 1970s and ‘80s as they forged what may have looked at the time like a “strange and wonderful” relationship.

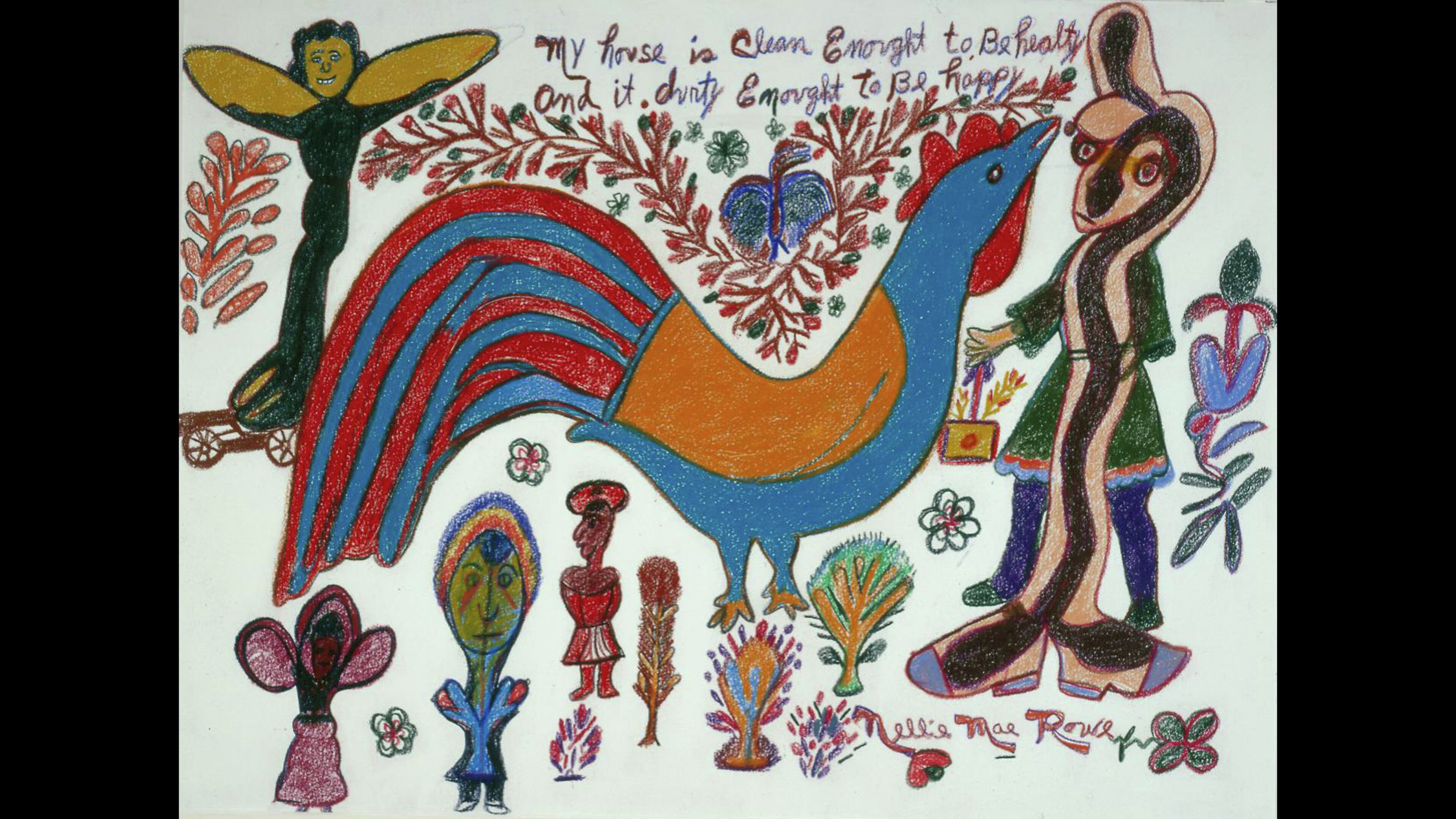

At long last, after a 20-plus-year hiatus, Rowe’s art, her vision, experiments, commentary and masterpieces are in full view at the High Museum of Art through Jan. 9. This show is a discernible labor of love, an exquisite curatorial undertaking by the High Museum’s Merrie and Dan Boone curator of folk and self-taught art, Katherine Jentleson. Included in the four galleries are examples of Rowe’s art in every medium she had a chance to explore: Recycled and found objects. Chewing gum. Ink, paint, pencils, colored pencils, crayons, oil crayons.

Included are representations of her carefully crafted dolls, her chewing-gum sculpture and a recreation of her environmental installations — what Rowe referred to as her “Playhouse” — surrounding the house that she and second husband Henry Rowe built and the one she transformed after his death and her subsequent retirement into an installation of yard art that drew over 800 visitors a year to her door.

In the galleries you will find a scaled-down facsimile of the exterior of her house and yard art environments, along with interior installations of work on the walls of her home, a practice of Rowe’s that originated in childhood.

The exhibition begins as you step off the elevator. What you first see is a huge, freestanding hot-pink wall, with her inimitable blown-up signature, “Nellie Mae Rowe.” The style is in a basic cursive script designed and modified by Rowe over the years.

Her signature appears throughout her work in a variety of iterations, sometimes loaded with versions of invented embellishments and sometimes simplified but always emphasizing the N, the M, the R. If she’d been of another generation, her signature could have functioned as a tag, like Basquiat’s. The story goes that Nellie would make a game of her signature with her nieces and nephews. A contest: Who could come up with the best, the best designed, the prettiest, the most creative, and then the joanin’: See if you can do it as good as I can. You can try, but you can’t do it as good as me.

Beyond the signature wall, we enter a spacious, airy-feeling and carefully organized gallery with an energy that flows throughout the exhibition in its entirety and evokes the spirit of the artist. Wall texts provide a biography of Rowe’s life and commentary on the works divided into sections: “Born on the Fourth of July,” “Experimentation,” “The Playhouse,” “Girlhood,” “At the Peak of Her Career” and “Guests of the Playhouse.” Emphasis is placed on Rowe’s spellbinding two-dimensional work. To refer to them simply as drawings is a disservice. They are a panoply of absolutely riotous explosions of color in tightly arranged and well organized compositional narratives.

In the gallery space you have an opportunity to compare and contrast these works to the scaled models of Rowe’s playhouse and yard art (recreated by Opendox films for the upcoming hybrid documentary on her life, “This World is Not My Own”). The spatial correlations found between the two are intriguing — a strikingly similar vision of utopia, Rowe’s utopia: An environmental theater, a playhouse created by a woman, an artist whose art evolved from a platform of autobiography into a complex, radical body of work that unpacks, discloses and reveals not only a self-taught artist but a self-taught philosopher.

Jentleson’s groundbreaking analysis in the exhibition’s show-stopping catalog unravels two major currents of meaning and significance; first, the inherent and hard-won feminism Rowe references and reveals in her art. Second, a formal connection existing between the three-dimensional constructs in her garden, her yard art — the organized, composed, 3-D space there — and the visual relationships she employs in her two-dimensional compositions. The formal similarities and characteristics are striking.

Throughout this exhibition of radically free expression, you see an artist whose work eclipses social bias and boundaries. The biographical details of Rowe’s life depict one of hardship born of poverty, hard labor and a dearth of educational opportunities due to economic oppression and prejudice. Yet what the artist elects to share in her work includes insights into Black culture and expression in an amazement of cultural escapades and practices most familiar within Black communities.

Notice for example, “Voting,” “Nellie Mae Making It to Church Barefoot,” “Pay House,” “Happy Days,” “Dear God Help Us To Keep Peace.” Rowe reveals a cultural bright side, beautiful, yet once obscured and protected from outside worlds.

Underneath an outside exterior made of systemic racism, discrimination and unconscious bias, Rowe — in her art, in her playhouse and through her interactions with visitors that came by the busloads to see her creations — chose to pull back the curtain to reveal a rich, cultural beauty extant in Black communities despite it all. She shared this culture, her culture, the profound beauty she recognized within it, with all who cared to take the time to stop, look and listen. And they did.

In “Real Girl,” a self-portrait of sorts, there is a photograph of Rowe holding one of her dolls and standing in front of a screened porch door with her name embellished upon it. The photograph of her is glued to the top of a page, surrounded by a hand-drawn heart, ensconced in an octagon, ensconced in a square forming a frame — layer upon layer upon layer.

The wall text by this work quotes her telling a reporter in 1979: “I am Black and I love my blackness.” Black is beautiful. Even when the subject is questionable, coded, foreboding, or mysterious, there is an inherent, brilliant beauty that prevails and transcends in all of Rowe’s work.

Complementing Jentleson’s work in the catalog are three additional texts, well worth the read, that continue to untangle the inherent complexities of Rowe’s life and art.

The first, titled “Really Free,” is a beautiful elegy to Rowe from polymath artist Vanessa German; next, “This World is Not My Own, A Creative Testament of Actuality” by Ruchi Mital, producer of the aforementioned hybrid documentary; and finally Destinee Filmore’s (2019-2021 Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow at the High Museum of Art) profound and instructive musings on the chair in Rowe’s work, a device used in several different capacities, subject to a variety of intriguing interpretations, underscoring the complete enthrallment that viewers shared over her work since its discovery.

Along with the research and testaments and a plethora of color reproductions, the catalog is a touchstone for the radical art of the really free Nellie Mae Rowe. As Catherine Fox, then visual arts writer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (and later co-founder of ArtsATL) described it in 1983: " . . . her art is a Valentine to humanity.”

“The world would be so much better, if we would love one another, treat one another right.” — Nellie Mae Rowe

Xenia Zed is a board member of the Judith Alexander Foundation, whose mission is to extend Alexander’s lifelong support of artists, assist the personal, financial and artistic concerns of Georgia artists and preserve the legacy of the late Nellie Mae Rowe.

Working closely with the American Press Institute, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is embarking on an experiment to identify, nurture and expand a network of news partnerships across metro Atlanta and the state.

Our newest partner, ArtsATL (www.artsatl.org), is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. Founded in 2009, ArtsATL’s goal is to help build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

Over the next several weeks, we’ll be introducing more partners, and we’d love to hear your feedback.

You can reach Managing Editor Mark A. Waligore via email at mark.waligore@ajc.com.