Race, gender and wealth almost let socialite’s husband get away with murder

On the last day of her life, socialite Lita McClinton Sullivan rose earlier than usual in her elegant Buckhead townhouse. Later that day a judge would decide on the division of property in her divorce from her multimillionaire husband, James Sullivan.

The date was Jan. 16, 1987, just a couple days after Lita’s 35th birthday.

At 8:15 a.m. her front doorbell rang. Wearing a white satin dressing gown, she greeted a man holding a long white box of pink roses wrapped in a big red bow. After thrusting the box into her hands, the man forced his way into the foyer, pulled a gun and fired a fatal shot to her head. After she collapsed, he fired a couple more shots into her body and fled.

Atlanta was shaken by the murder. The ‘80s were a violent time in the city, but the elite, white enclave of Buckhead had seemed immune. Knowledge that the victim was Black and in an interracial marriage — rare among that social strata, especially at that time — raised questions. Adding intrigue was the macabre image of a killer bearing roses.

It didn’t take long for all indications to point at James Sullivan as the key suspect in a murder-for-hire scheme, but it would take nearly two decades for him to be brought to justice.

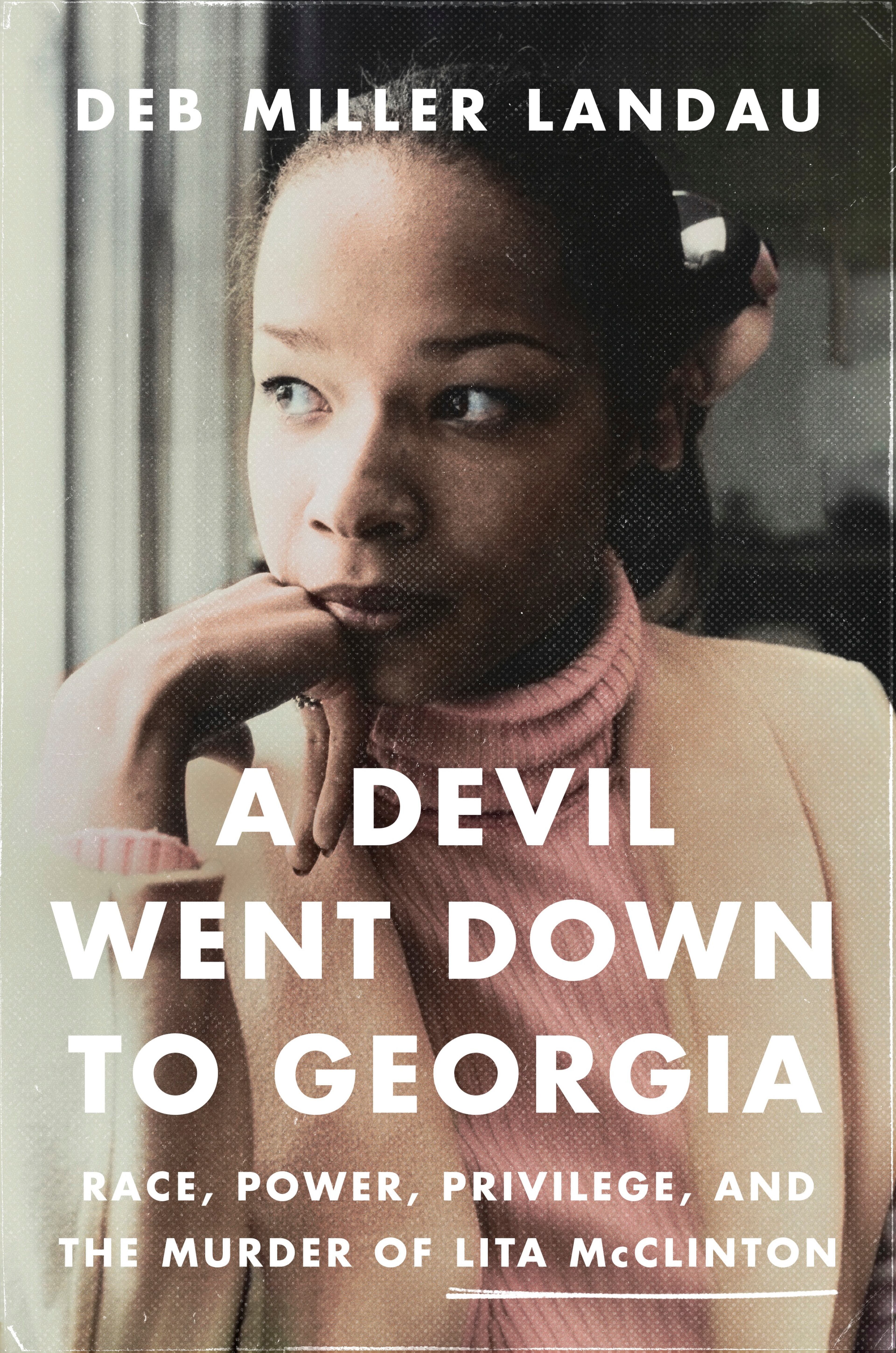

The murder, the investigation and the court case that followed are the subject of the illuminating new book “A Devil Went Down to Georgia” (Pegasus Books, $28.95) by journalist Deb Miller Landau, who first wrote about the case for Atlanta magazine when Sullivan was extradited to the U.S. from Thailand in 2004.

Ever since then, Landau has held onto a bankers box of notes related to the story and was prompted to revisit it from a new perspective to figure out why it took so long to resolve the case.

“I was very, very moved by meeting [Lita’s] parents at the time in 2004,” said Landau, speaking from her home in Portland, Oregon. “When I got my hands on the story the first time, it was already 17 years after the murder, so I was coming at it with some perspective. Having seen what this family had gone through to get justice for their daughter, it just felt so disgraceful. Why did it take so long? I don’t know that I ever understood why it took so long and what really happened.”

Looking at the case through eyes enlightened by the #MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter, Landau concludes that because of his wealth and white privilege, Jim Sullivan nearly escaped punishment for the murder of his wife.

“All the justices were white, all the attorneys were white, all the FBI and GBI guys were white. … I don’t think the police work was inherently racist in its intent, but I think there was a lot of subliminal activity around the case that did have to do with race,” said Landau. “We tend to give rich white guys the benefit of the doubt, and we give them a lot of leeway in terms of values and what they say and what they’re allowed to do.”

That said, James Sullivan came into privilege later in life when he inherited a Macon-based wholesale liquor distribution company from his uncle. But Lita Sullivan was born into privilege. She grew up in Cascade Heights, the Black equivalent of Buckhead. Her mother, JoAnn McClinton, served in the Georgia House of Representatives for more than a decade. A debutante, Lita was among the first Black students to attend St. Pius X Catholic High School. She was a Spelman Woman who studied political science.

“She had learned to navigate white spaces, Black spaces, interracial spaces,” said Landau. “She was extroverted, somebody who liked to have a lot of fun.”

Lita was working at T. Edwards, a high-end clothing boutique in Lenox Square, when she met James Sullivan, a Boston native from a blue-collar family with Irish roots. He was smart, charismatic, wealthy and ambitious. He was also 10 years older than Lita, who was 25 when they met.

To her parents’ dismay, the couple married soon after meeting in 1976. They eventually moved to a mansion in Macon where James tried to buy his way into high society while remaining blind to the racially charged cold shoulder his wife received. They later move to a bigger mansion in Palm Beach, Florida.

Initially in their marriage, Jim showered Lita with expensive jewelry and lavish trips. Then came his infidelities and controlling behavior.

Lita had to “account for every dime she spent, sneak salon visits, beg her husband to let her wear the jewelry he’d supposedly bought for her,” Landau writes.

In her divorce affidavit, Lita wrote that Jim “consistently used money as a weapon against me and would cut off all my financial resources whenever he became angry.”

Meanwhile, he squired his mistress, Suki Rogers, around town in a Rolls-Royce and established a reputation as the kind of man who berated waiters for the slightest mistake and engaged in road rage.

“He was nasty. He was a real sociopath,” John Connolly, a former New York City detective turned journalist who wrote a scathing profile of James Sullivan for Spy magazine, told Landau. “He could be charming, but he could turn on you like a cobra.”

Eventually, Lita had enough. She moved back to Atlanta, taking up residence in their Buckhead townhouse, and filed for divorce.

The ‘80s were a pivotal time in the city’s history. The Atlanta child murders were coming to an end, but the murder rate was on the rise. CNN had just become a 24-hour news channel. Spaghetti Junction was under construction. The Hawks were the team to watch.

“The city’s growing rapidly,” said Landau of that time. “Largely due to the Atlanta University Center, it’s producing a lot of very highly educated, powerful Black folks. It was a time of a lot of real growth for the Black community in terms of power in the South. … It was just a real time of change, and it was for Lita, too. She was getting out of this marriage that really robbed her a lot of her spark, and she was finding herself again when Atlanta was also finding itself in a new way.”

Instead, her life was cut short.

Landau’s deeply reported account of the murder investigation is a stark reminder of how far we’ve come in the realm of forensics. At the time of Lita’s murder, there was no internet, no cellphones or cellphone tower pings, no national fingerprint database.

“It was a lot of boots on the ground investigation,” Landau said. “They didn’t have much to go on. They didn’t have a murder weapon. They didn’t have a murderer. They had very few clues. … There was a lot of just asking around.”

Meanwhile, “Jim was leading the detectives on all kinds of goose chases, suggesting she had been involved in drugs, that she had been unfaithful in their marriage and the fact she was dating multiple people,” she said. “For a time, he even made the suggestion her parents had her killed so they could collect on her insurance policy, which is just so brutal and disgraceful.”

Jim was eventually indicted and went to trial in federal court in 1992, but the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. A civil suit followed, finding Jim guilty and awarding a $4 million settlement to Lita’s parents. Meanwhile, the criminal investigation continued as the five-year statute of limitations for a murder-for-hire charge was drawing to an end.

When authorities finally started to close in on hit man Tony Harwood, Jim fled the country first for Costa Rica and then Thailand, where he was caught and extradited back to the U.S. to stand trial. In 2006, he was found guilty of malice murder and felony murder, among other charges, and sentenced to life without parole. He’s serving time in Macon State Prison.

Justice was a long time coming, and Landau credits Lita’s parents with keeping her case alive, as well as Florida lawyer Brad Moores, who filed the civil suit, and private investigator Patrick McKenna.

“They worked with the family for decades to try to get justice and also to try to keep the GBI involved because it started to go cold pretty quick,” said Landau. “If not for them pushing and pushing and pushing the media, if not for them pushing the authorities using the powers that they had to move the case forward, I think Jim would be living in Thailand today.”

Author events

“A Devil Went Down to Georgia”

Author Deb Miller Landau will be in conversation with Lisa Rayam. 7 p.m. Aug. 12. $10. McElreath Hall at the Atlanta History Center, 130 W. Paces Ferry Road NW, Atlanta. 404-814-4000, www.atlantahistorycenter.com

Georgia Center for the Book presents Landau in conversation with Jill Cox-Cordova. 7 p.m., Aug. 13. Free, registration required. First Baptist Church of Decatur, 308 Clairemont Ave., Decatur. georgiacenterforthebook.org

Landau will be conversation with Winfield Ward Murray, professor of race and law at Morehouse College and a federal immigration judge. 6:30 p.m. Aug. 15. Free, registration required. 44th & 3rd Bookseller, 451 Lee St. SW, Atlanta. 678-692-6519, 44thand3rdbookseller.com