Quilting program provides comfort and new skills to local prisoners

In a classroom in South DeKalb County six women piece together blocks of cloth for quilts as they attempt to piece together their lives. After being imprisoned on a variety of serious offenses, they have earned transfers to the Metro Transitional Center, a minimum security facility designed to help them re-enter society.

Shannon Waters, 46, carefully places black and red strips of fabric together to make a log cabin pattern for a baby. She’s read that red is the first color infants can distinguish. “I love it,” she says of the stack of blocks on her machine. “I want to keep it for myself.”

An airplane mechanic in her pre-prison life, she’s never sewn before and at first found the idea of a quilt intimidating. “If you break the quilt down to squares, it’s easier,” she says.

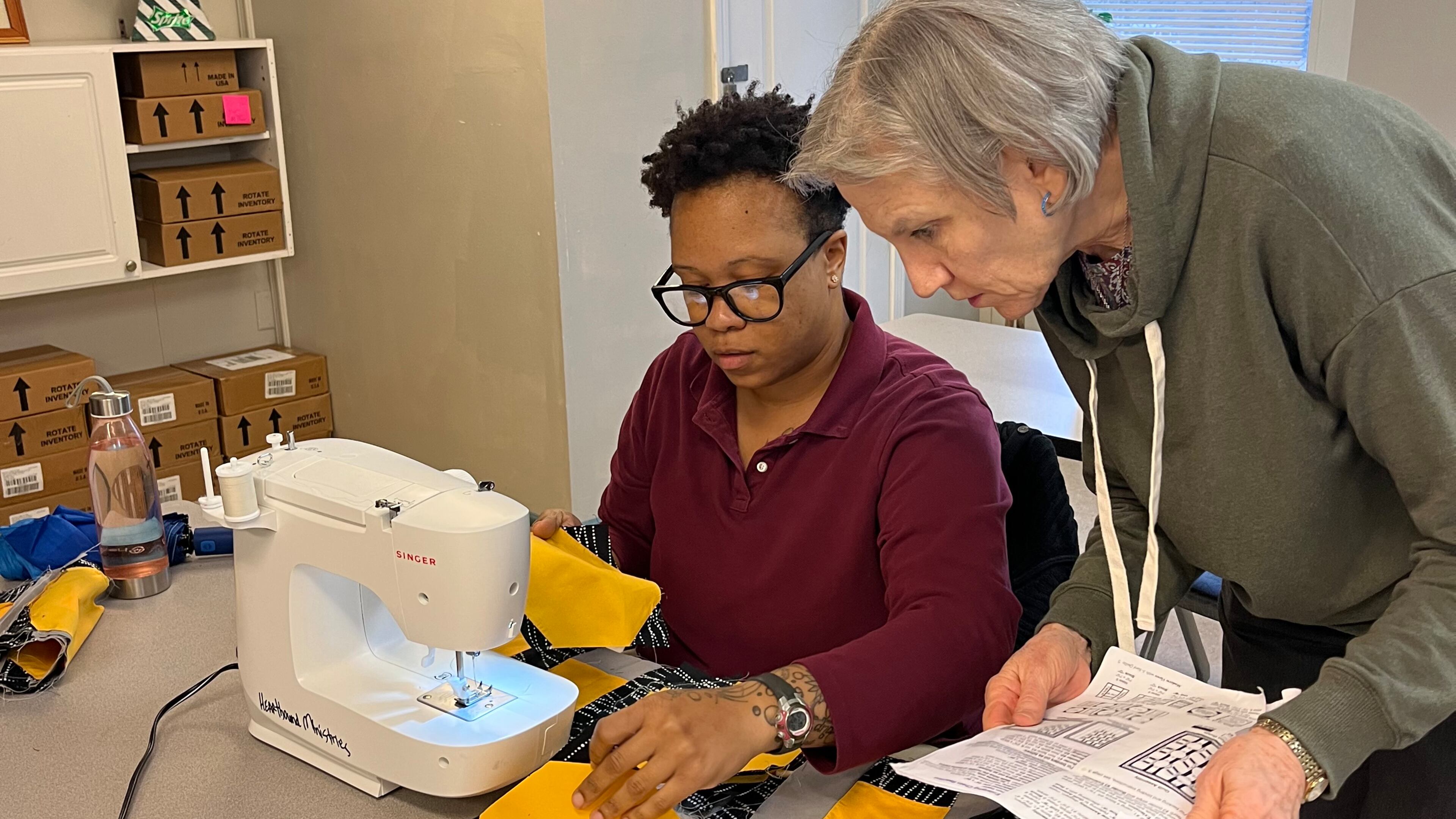

At the sewing machine in front of her Candice Boles, 37, is stitching together blocks of gold, black and gray in the Chain Reaction, from a book by quilter Donna Robertson, pattern for her 15-year-old daughter. Unlike Waters, she has sewn — but only men’s prison uniform pants while in a higher security facility. These Wednesday afternoon classes offer a mental escape, she says. “It’s you expressing your creativity. You’re piecing things together to make something beautiful. It’s a zone you enter into.”

“Some things get very stressful in here,” says Amy Lynn King, 31. “I needed a get-away space.” She’s put her blocks together — a sports theme with blue borders for the three sons she hasn’t seen in seven years — and is learning to do the actual quilting.

The class is taught by volunteers led by Elizabeth Beck and Fonde Werts. Werts is a retired English for speakers of other languages teacher who has also taught quilting to children and adults. “I saw what learning to quilt did for little girls whose families can afford to pay,” she says. “I knew that it would do the same for these women.”

Teachers regard the beginning quilters as students, not prisoners, she says. They never ask about the offenses behind the incarcerations.

A major aspect of the class is allowing the women to choose their own patterns and colors. “They don’t have a lot of choice in their lives,” she says.

The quilting class is a facet of Art From the Inside, a program that gives incarcerated men and women an opportunity to express themselves through various forms of art. Its founder, Lucy Fugate, is following in the steps of her grandmother, Pauline K. Wiggins. While going through a bin of old family material, Fugate found a drawing of her grandmother which, it turned out, had been done by a prisoner at Mississippi’s Parchman Prison Farm where her grandfather, Marvin Wiggins, was superintendent. Fugate learned that in the early 1950s her grandmother had begun sponsoring an annual “hobby show” for Parchman inmates that eventually was drawing more than 600 entries.

Fugate approached HeartBound Ministries and the Georgia Department of Corrections and the first Art From the Inside show took place in 2017. The quilting class came about in July 2023. It has a waiting list.

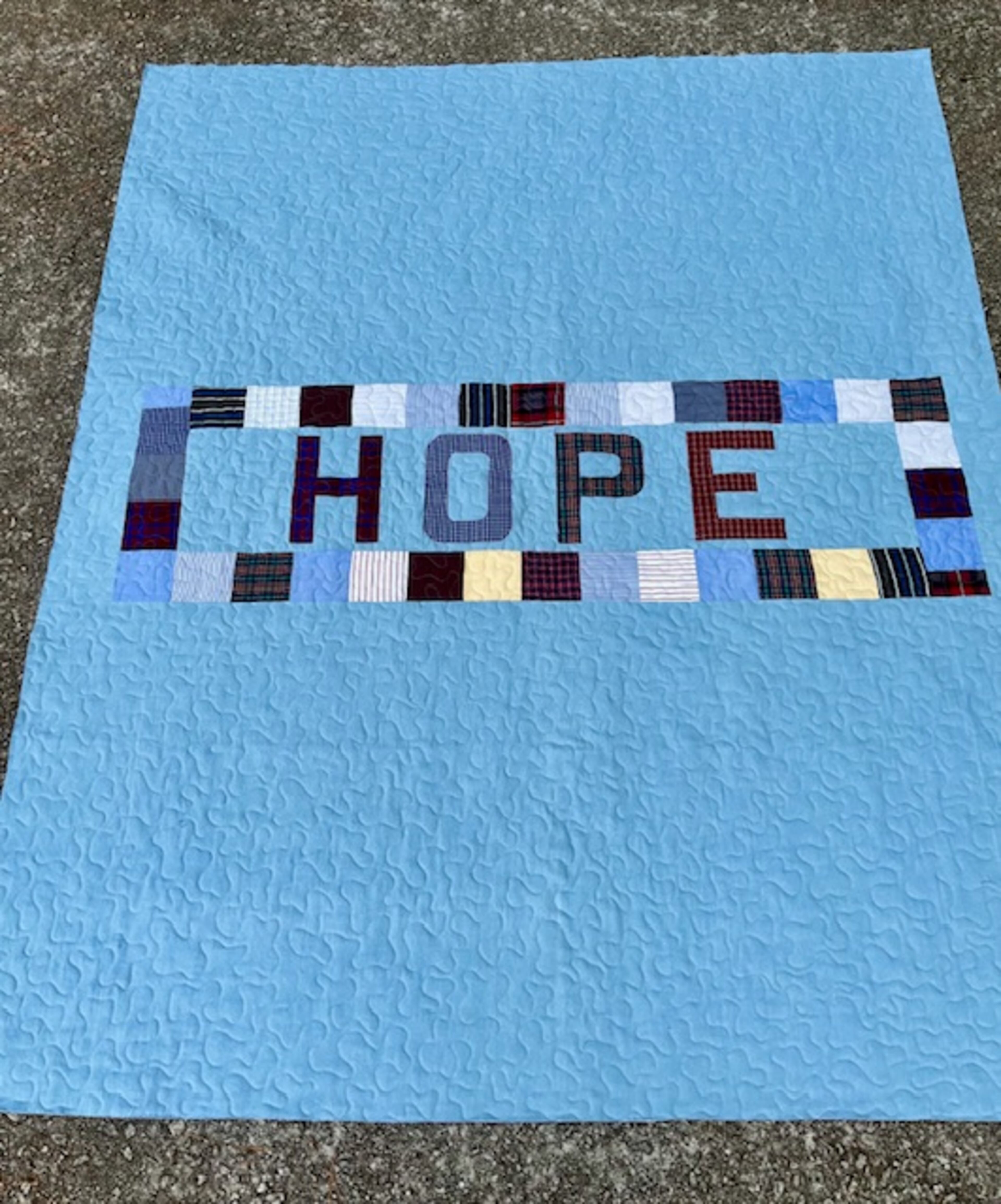

Superintendent Wendy Jackson of the transitional center says she is happy to have the quilting class on site. “I found comfort in a quilt I got from my grandmother,” she says. “We wanted the inmates to have that same comfort.”

To walk inside the quilting class, she says, “is a feel-good experience.”

Art From the Inside, in turn, operates under the umbrella of HeartBound Ministries, a nonprofit organization that provides programs and resources to support prisoners, their families, and corrections employees.

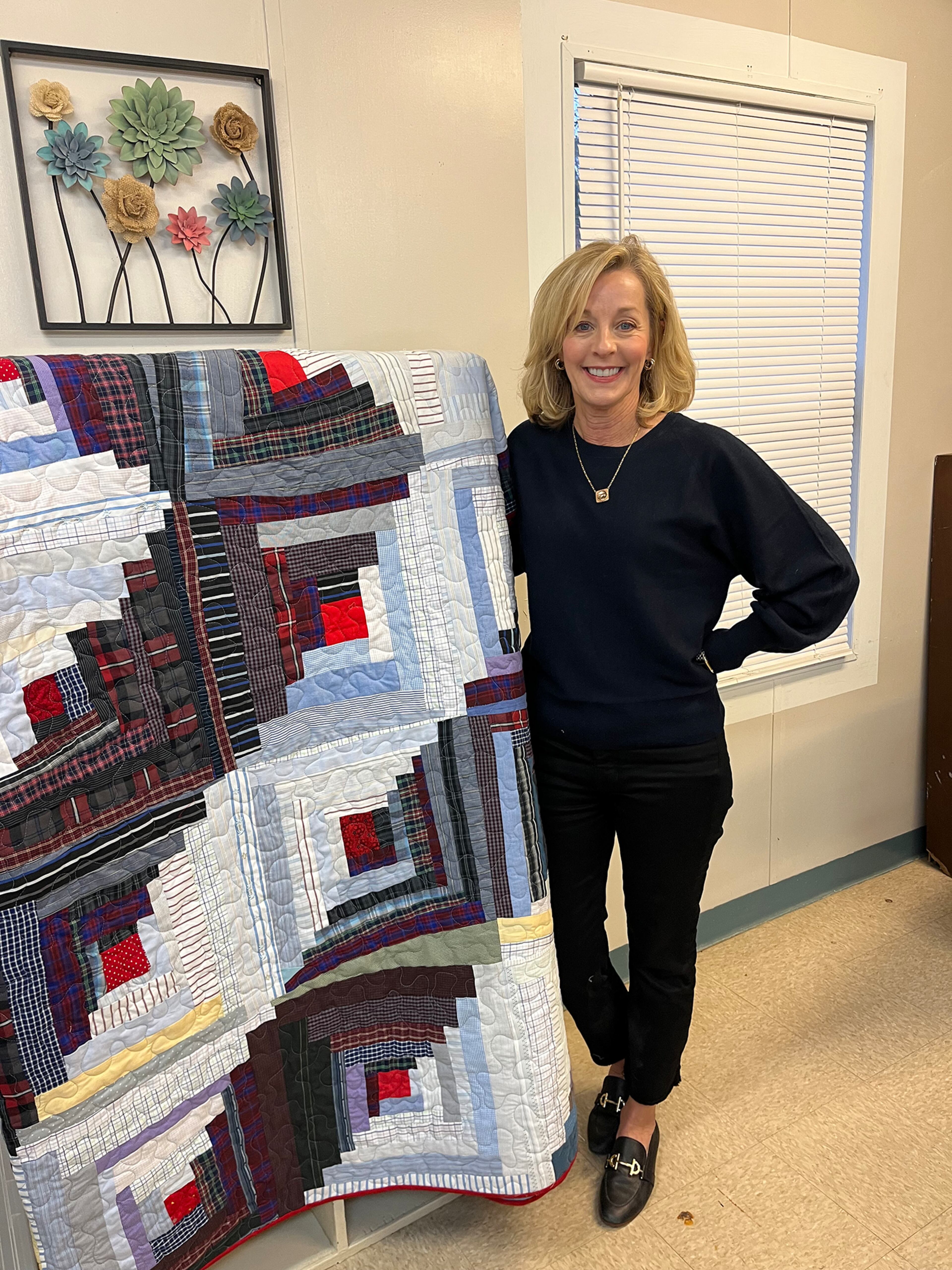

While not working on their own projects, the transitional center quilting classmates are making a communal quilt to be auctioned at a fundraising gala for HeartBound Ministries on Nov. 30. Their first collaborative effort was on display at Oglethorpe University Museum of Art this fall. The women were allowed to take a field trip to the exhibit.

Seeing their work alongside the work of other inmate artists was enlightening, says Shannon Waters. “The perception of people in prison is of not having a lot of skills. We do have skills that we can utilize outside of here.”

“It was amazing,” Boles says of seeing their quilt at the museum. “We’re all so different and we came together to put together one quilt that represents all of us. It’s beautiful.”

She says learning to quilt has given her confidence that she can learn other skills. After doing a series of service jobs before her conviction, she’d like to earn credentials to teach African studies and culture after her release, scheduled for 2026. “I went outside my comfort zone to do this,” she says of the quilting. “You don’t think you’re capable of it, and then you see the final product. I can quilt! If I can do this, there’s nothing I can’t do.”