Some say Lake Lanier is cursed. Atlanta podcast explores truth behind the myth

For decades, it has been rumored that Lake Lanier is haunted by the dead Black residents of a town called Oscarville that was supposedly flooded when the lake was being developed in 1955. The story usually goes one of two ways: either the all-Black town was purposely obliterated by floodwaters, or that the flooded graveyard of a once Black town created vengeful spirits.

TikTok rappers have spit rhymes about the cursed lake; Instagram influencers have spread the legend; even Georgia ghost tours have told the tall tale.

“Swimmers have reported feeling unseen hands grabbing at their legs, pulling them under. These unexplained phenomena have contributed to the belief that Lake Lanier is haunted by the spirits of those who perished in its waters or whose graves were submerged during its creation,” reads a blog for a ghost tour company, Atlanta Ghosts.

Like a game of telephone, the stories have unraveled into many false narratives. If one follows the rumors backward, however, they do connect, albeit loosely, to a thread of truth. That truth is the subject of a new podcast, “1912: The Forsyth County Expulsion and its Aftermath.”

The five-part series is produced by Atlanta History Center, distributed by WABE (metro Atlanta’s NPR and PBS affiliate station), and cohosted by journalist Rose Scott and Atlanta History Center researcher Sophia Dodd.

“We’ve created something really extraordinary,” said Kristian Weatherspoon, vice president of digital storytelling at Atlanta History Center. “It is a work that bridges the past and present with insight, rigor and heart. The story is about so much more than history. It’s about recognition — recognition of truths too often hidden behind myths.”

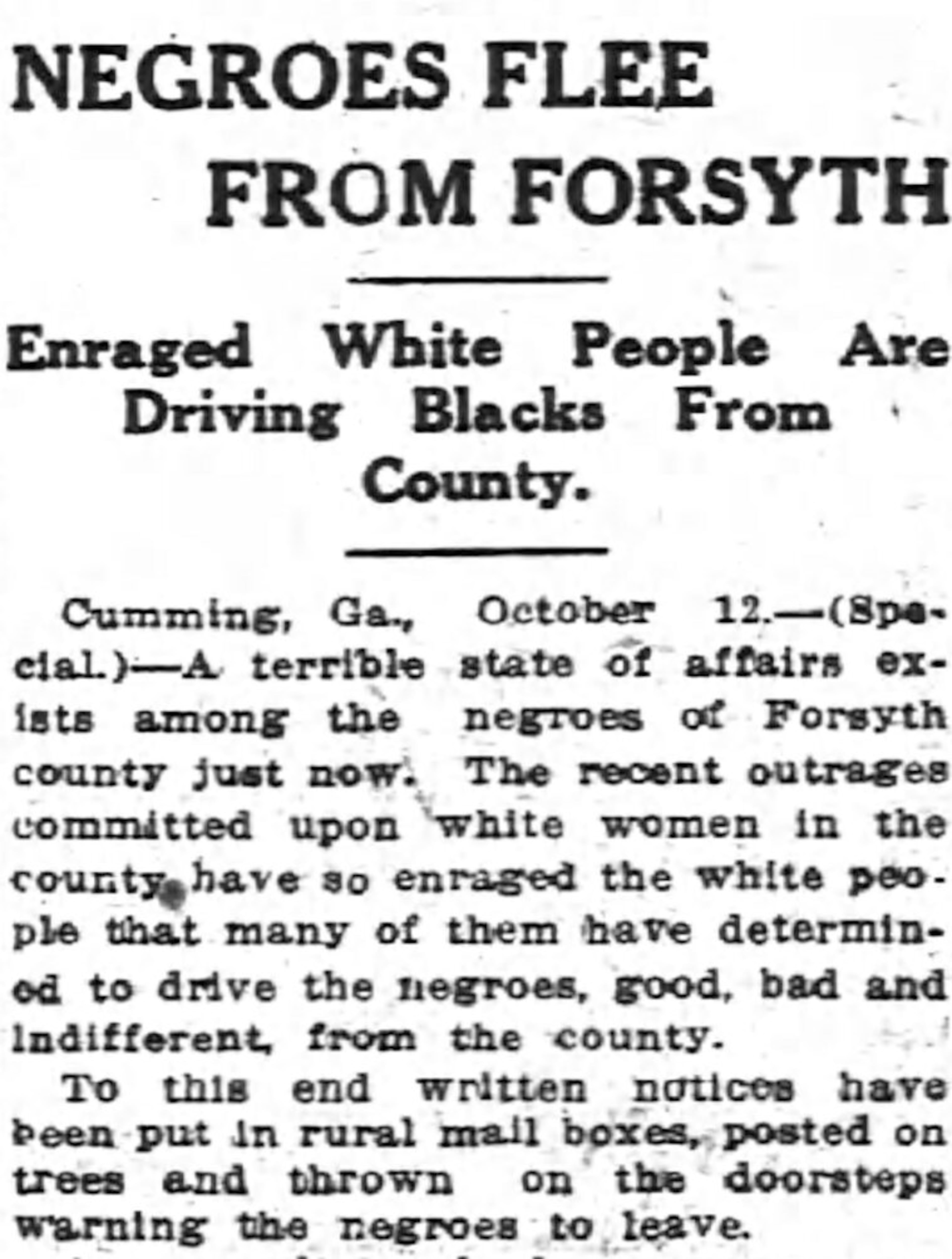

The podcast unfolds the backstory of Forsyth County in the early 1900s, which saw simmering racial tensions boil over into violence, including public lynchings, ransacked homes and eventually, the expulsion of an entire Black community by angry white vigilantes known as the “night riders” who set aflame some Black-owned homes, threatened others and posted written notices.

The events that proceeded the expulsion included one young white woman claiming a Black man sexually assaulted her, followed just four days later by a group of locals discovering a white 18-year-old Oscarville resident savagely beaten in the woods.

In the game of telephone, Oscarville was storied to have been the Black town flooded by Lake Lanier. In reality, Oscarville was the white town where a resident being found beaten was the catalyst to set off the 1912 expulsion of every Black person in the county decades before the creation of Lake Lanier. All these truths, and more, are explained through Dodd’s extensive research and interviews with some of the descendants of the roughly 1,000 Black residents who were run out of Forsyth County.

Atlanta History Center has also created a museum exhibition, digital exhibit and interactive maps to supplement the podcast’s storytelling.

On Nov. 18, descendants and the general public were invited to Atlanta History Center to unveil the exhibition and attend a panel discussion with Scott, Dodd, a graduate student researcher from Clark Atlanta University, Monica Goings, and three descendants of the expelled Black residents, including Elon Osby, a descendant of William and Ida Bagley; Charles Grogan, a descendant of Russell and Rosalee Strickland; and Chase Evans, a descendant of Jim and Rosanna Strickland.

In the audience were roughly another 40 descendants, as estimated by the organizers. Among them were Charlie Lee Wiley, Edith Lester, Bridget Evans and Mattie Conley, whose relative Leola Strickland Evans was pictured in the exhibition. Leola was only three when her family was forced out of Forsyth.

“My mother was one of them,” said Conley. “She shared with me that ‘They run us out and all I had was my little doll.’ Every year she saw to it that her girls had a doll. She had a bed full of dolls when she died.”

“I guess that’s why she loved dolls,” added Wiley, Leola Strickland Evans’ grandson. “I used to sit at the feet of my grandparents, Matthew Evans and Leola Strickland Evans … she talked about it [her home in Forsyth] and she would call it the old homestead … it is almost like she would get lost in the memory wishing that she could go back and see it.”

While Leola Strickland Evans never did go back to see her childhood home in Forsyth, Wiley did. Thanks to some research done by Marco Williams, a documentarian who produced a film called “Banished” that also featured the Forsyth story, Wiley was able to locate the plot of land that was once his grandmother’s. Together Wiley, his mother and some of his cousins, aunts and uncles stood emotional on the land.

“I’m just loving that they’ve done the research and have it all documented now,” said Wiley of Atlanta History Center. “You often say that there’s a thread, you pull on the thread and things unravel, but this [project] is kind of in reverse. You bring all the threads together and make this tapestry so you’re actually creating something … it is coming together … I’m learning things here myself that I didn’t know.”

The “1912: The Forsyth County Expulsion and its Aftermath” podcast premiered with two episodes on Nov. 19. A new episode will be released weekly. Listeners can find the podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and on WABE. The digital components and interactive maps can be found on AtlantaHistoryCenter.com. The in-person exhibition is now on display in the lobby of Atlanta History Center and can be viewed for the next year.