OPINION: The historic churches that saved Black America need saving

In the beginning, a group of enslaved Georgians came together to form what would become Big Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

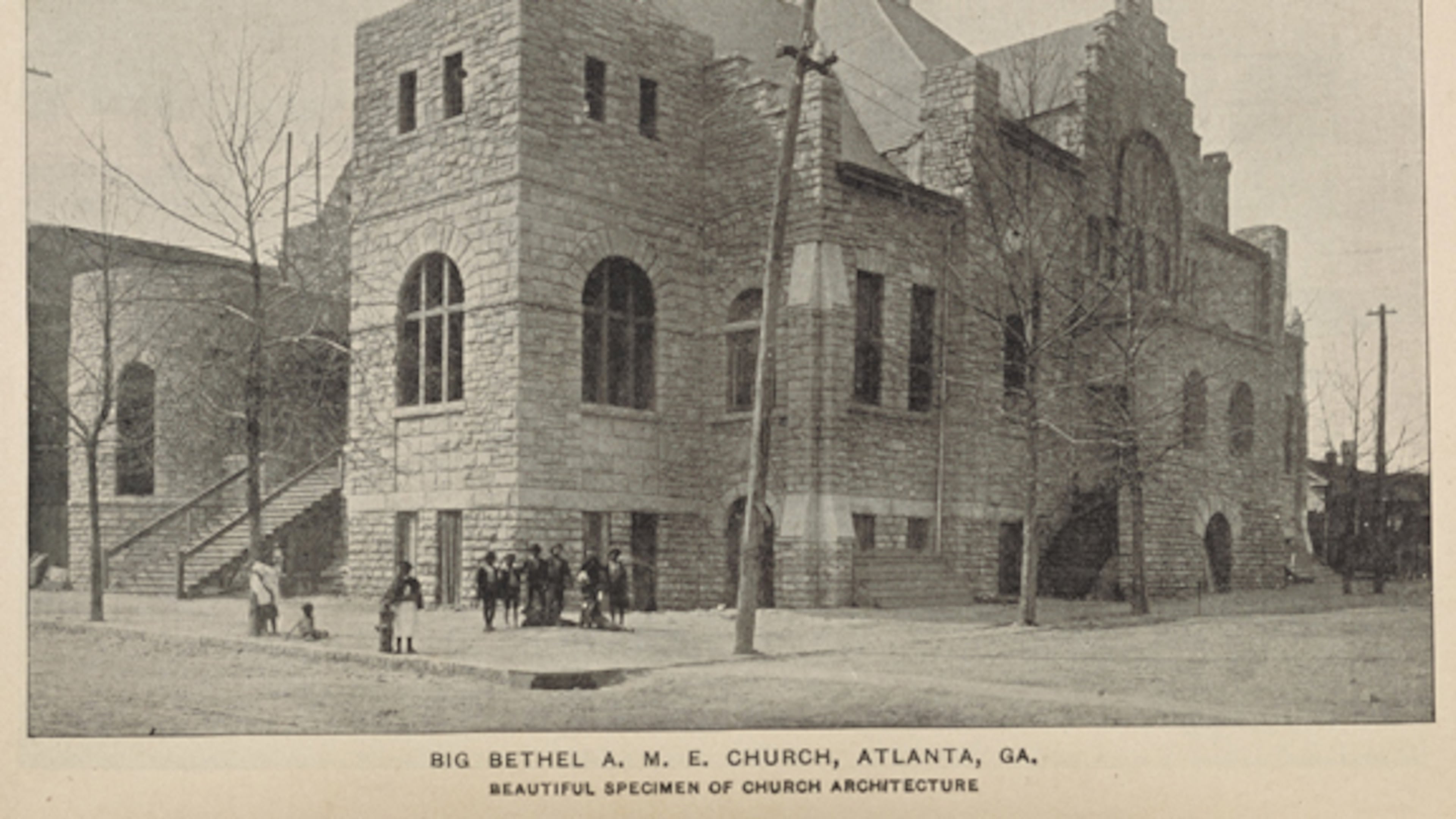

The original building where congregation members began meeting in 1847, where they came to pour out their sorrows and find solace, no longer exists. Neither does the Bethel church that made its Auburn Avenue debut in 1891 only to be later destroyed by fire.

The Big Bethel AME Church that stands today was restored in the 1920s by the Black architect J.A. Lankford and a Black builder, Alexander Hamilton. For a century, it has traversed the ups and downs of its urban placement while continuing to play a prominent role in the development and promotion of Black culture.

It’s fitting to start Black History Month by recognizing the integral role the Black church has played in shaping that history.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Black church saved Black culture when it was most in peril.

“The Black church was the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designed to crush their spirit,” wrote Harvard University scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. in his 2021 book, “The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song.”

These were the places that bolstered an oppressed people and steeled them for the outside world. These were the places that allowed for freedom of expression in music, dance, philosophy and more. These were the places that prepared Black people for leadership roles.

I was raised in a Lutheran Church. And, while our congregation was predominantly Black, I would stop short of calling it a Black church.

But, on some Sundays, we’d go with my great-aunt and her husband to services at Olivet Baptist, one of the oldest Black churches in Chicago, founded in 1850, which once served as a station on the Underground Railroad. At Olivet, the spirit was different. Tears would well up in my eyes when I heard the choir sing a stirring gospel or when I felt the emotion of the congregation as the pastor gave his sermon.

Even as a child, I knew those moments at Olivet were connecting me to something much greater. The service always ended with a joyful celebration of food and fellowship during which ladies whom I had just met kissed my cheeks and slid crumpled dollar bills into my palm as my aunt and uncle bragged about my accomplishments.

In Atlanta, Big Bethel is believed to be the oldest Black congregation. It was the home of the Gate City Colored School, the city’s first public school for African Americans, and was the birthplace of Morris Brown College.

Big Bethel, with its iconic “Jesus Saves” on the steeple, is among the more than 75 Black churches nationwide that are at least a century old and continue to operate today.

It’s also one of the ones in need of rescue.

I’m happy to report that some of them are receiving that help. The Lilly Endowment and the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund are investing in an initiative to “help historic Black churches and congregations reimagine, redesign, and redeploy historic preservation to address the institutions’ needs.”

Black churches around the country were collectively granted $4 million in January during a second round of funding designed to save the declining structures.

In addition to Big Bethel in Atlanta, the Georgia churches that received funding include First Missionary Baptist Church in Thomasville and St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Fort Valley.

St. Luke’s was designed circa 1940 by Stanislaw J. Makielski, the official architect for the American Church Institution for Negros. The church was part of the effort to develop education facilities for Black people in the rural South.

First Missionary Baptist was constructed between 1890 and 1900 by formerly enslaved congregants. The Queen Anne-style church has hosted Black luminaries throughout the years, including Jesse Jackson and Shirley Chisholm.

It’s interesting that, at a moment when we are striving to save churches, we as a nation are becoming increasingly nonreligious. Among American adults, 28% have no religious affiliation as compared to 16% in 2007.

The trend however is largely driven by white Americans, who account for 63% of the nonreligious (that includes atheists, agnostics and nothing in particular) compared to 9% of African Americans, 17% of Hispanics and 7% of Asian Americans.

For Black people, even those who no longer attend church on a regular basis, there’s a recognition that our fate on earth is intertwined with our faith.

In a 2021 focus group on how Black Americans talk about Black churches, participants concentrated on the many ways in which historic Black churches have served the community. In that study, conducted by Pew Research Center, people spoke glowingly of Black houses of worship because they believe that kind of action must continue.

“These places of worship, these sacred cultural centers must exist for future generations to understand who we are as a people,” said Gates, who serves as adviser to the Action Fund.

The church remains a place of comfort for many Black Americans, a force for change. And that’s what’s being preserved, not just the buildings.

Read more on the Real Life blog (www.ajc.com/opinion/real-life-blog/) and find Nedra on Facebook (www.facebook.com/AJCRealLifeColumn) and Twitter (@nrhoneajc) or email her at nedra.rhone@ajc.com.