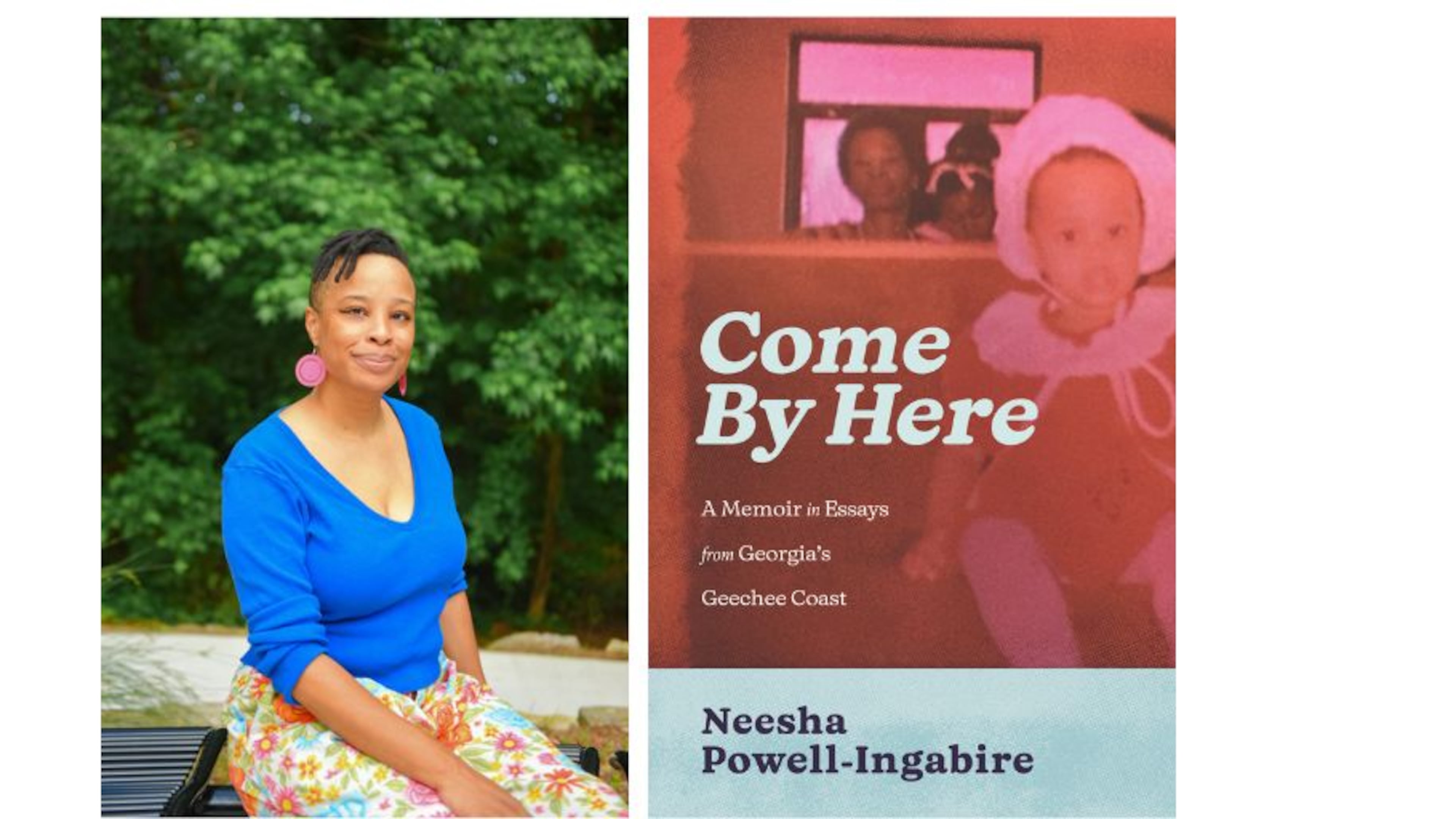

Journalist explores Geechee Gullah roots in ‘Come By Here’

In “Come By Here: A Memoir in Essays from Georgia’s Geechee Coast,” a collection of 20 poignant and searching essays and photos, journalist Neesha Powell-Ingabire combines her coming-of-age journey growing up on the Georgia coast with her adult exploration of her Gullah Geechee lineage — which her family historically shunned. Through the process of connecting with her ancestry, she becomes an advocate for reclaiming African traditions as a path toward healing for Black Americans living in a society plagued with racial injustice.

“I am part of a generation of Black creators who seek to remove the stigma of descending from enslaved Africans,” Powell-Ingabire writes.

After living elsewhere for a decade, the author returned to her hometown to report on the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery, the 25-year-old Black man killed by vigilantes while jogging in Glynn County. The author was horrified, but not surprised, that Arbery’s murderer was a white man she recognized from her high-school Spanish class.

Reporting about life in Brunswick was enlightening and introduced her to the Gullah Geechee community. The descendants of enslaved West Africans living off the coast of the Southern states, the Gullah Geechee “blended practices from their native land and their new home to create their own distinct arts, language, food and spirituality.” They retain a strong connection to the water through fishing, the land through farming and the traditional customs that have ensured their survival and set them apart.

But their way of life is being threatened. The popular tourist destination St. Simons Island once boasted a thriving community that is declining because of water pollution and gentrification. In her essay “Water is Life,” the author reports that “African Americans once owned 86% of the island. The 2020 U.S. census reported the island’s Black population as 2%.” Hog Hammock used to be one of many Saltwater Geechee (island-dwelling) communities on Sapelo Island in McIntosh County. It is now one of the last in existence.

While researching a story on how water pollution impacts fishing and food security on the Georgia coast, Powell-Ingabire recognized how her own genealogy fit in with Geechee history. Because it wasn’t perceived as beneficial to claim Geechee heritage, the author believes her family rejected this identity in the past.

In “Water is Life,” the author encounters author and activist Marquetta L. Goodwine, known as Queen Quet, Chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation, who tells Powell-Ingabire “you may not claim us, but we’re still going to claim you.” She encourages the author to inspire her family to recover their lost roots.

Identity is a dominant theme throughout the collection and a concept Powell-Ingabire examines from multiple angles. “For centuries, either others have dictated to us who we are, or we’ve been told we have no culture at all,” Powell-Ingabire writes in “Reclamation,” a piece that advocates for a return to farming to heal the African diaspora.

“Our ancestors were stolen precisely for our agricultural prowess,” she says about her visit to Gilliard Farms in Brunswick getting to know the seventh Gullah Geechee generation to farm their ancestral land. “What if Gilliard Farms is a glimpse of an Afrofuture where Black people’s relationship to food and land is regenerative instead of fraught?” She notes that 100 years ago, Black Americans made up 14% of the nation’s farmers; today they comprise 1.4%.

Loss is something Powell-Ingabire grapples with how to portray in more than a few essays. She is, self-admittedly, an outsider who doesn’t want to be “one more intruder” exploiting Geechee stories for gain and aims to focus on the preservation, not the disappearance, of this culture.

In a piece titled “Stealing Sheetrock,” the author takes umbrage with Melissa Fay Green’s 1991 National Book Award finalist “Praying for Sheetrock,” a narrative about civil rights in the 1970s. Powell-Ingabire feels Greene portrays the Black residents of McIntosh County as “sleepy and subservient,” and Harvard history professor James E. Goodman agrees. Powell-Ingabire cites his review of Greene’s book, in which he takes issue with the author’s omission of Black people’s post-emancipation struggle from her story.

Powell-Ingabire asserts Greene “commits historical erasure” by depicting her subjects as helpless and glosses over important history like the complexity of the Gullah Geechee language in favor of highlighting the Scottish history of McIntosh. Powell-Ingabire believes Greene missed the plot of her own story by arguing the reason McIntosh remained segregated well into the ‘70s was because of white suppression.

“She assumes Black people in McIntosh wanted integration,” Powell-Ingabire writes, noting that groups that have been historically exploited or marginalized may prefer to live separate for their own safety. Powell-Ingabire vows to do better than Greene did for a community she deeply respects and who may indeed be kin.

Returning to the concept of ancestry, one of the most moving pieces in the collection is “A Treatise on Black Women’s Tears.” The author combs through her experience receiving mental health treatment and how it opened her up to the concept of healing through weeping. Researching “the long-standing and well-documented relationship” women have with public wailing, Powell-Ingabire reflects on her ancestors enduring one of the largest Georgia slave auctions in U.S. history known as the “Weeping Time.” Her ruminations are deep and profound as she explores these intergenerational bonds with sensitivity and deference.

Neesha Powell-Ingabire has a lot to say about the world she lives in and how it can improve. Part memoir, part family history, part action plan, “Come By Here” is a rousing work that delivers a compelling treatise on how reclaiming African traditions can move the lives of Black Americans forward.

NONFICTION

“Come By Here”

by Neesha Powell-Ingabire

Hub City Press

272 pages, $17.95