On a small U.S. island there is a young man named Kurt Marsh Jr. He lives with his extended family on land that has been in his family for countless generations. Before that his family worked the land as enslaved people.

Just steps away from Kurt’s generational housing are jewelry stores and luxurious hotels; restaurants too expensive for the average person to eat at more than once or so a year. Because of these touristic amenities, every year, every day sometimes, there is a request for this land to be sold to a developer or bought by a rich mainlander.

The taxes alone, reflective of the luxurious hotels in the area, go so high that islanders are often forced to sell or have their homes repossessed. Even now, at the time of this review’s publication, one of Kurt’s cousins is being sued for his water front property.

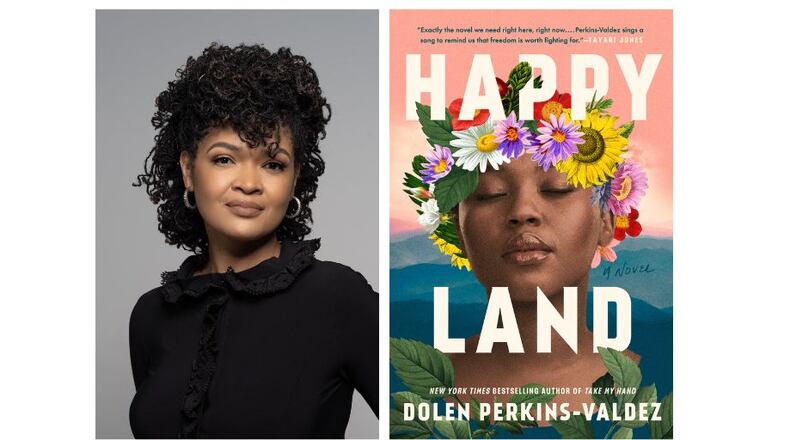

In Dolen Perkins Valdez’s new novel “Happy Land,” she tells us a fairy tale, one of kings and queens and princesses. There is a castle. There is good and there is evil, and there is much in between. As in so many fairy tales, there is also a love story that compels the narrative — it even ends with a wedding.

And yet, “Happy Land” is also based on something entirely true: a real place, with this same perfect name where formerly enslaved people made a kingdom, and the history of land dispossession in the United States post-Reconstruction.

The novel follows two narratives. Nikki, almost 40, has been summoned by her grandmother for reasons unknown. Nikki’s own life, with her adult, underemployed daughter and the real estate job she’s disenchanted by, feels like “a mess.” Though a character in this book, Nikki isn’t a reader. She picks up one of her grandmother’s books “looking for pictures.” (Reticent readers might see themselves in her — after all, the character is them.)

Unbeknownst to Nikki, her journey is a backwards one. She is returning to her grandmother, to her land and to the story of who her people were. The paperwork skills she has as a real estate agent are put to work as she goes deep into the archives of the local library to research the history of her grandmother’s property and Happy Land itself.

As an archivist, Nikki becomes an approximation of the historical novelist, meticulously sifting through archives and asking lots of questions. In this way, Nikki pieces together a story of what was. What Nikki finds is the second narrative.

This one is about Luella. Luella is going forward. She begins her narrative walking away from the place of her enslavement, compelled by the handsome and charismatic man she will marry. They are heading to make a new place — the kingdom of Happy Land.

In this kingdom they will rethink the religion that their enslavement taught them, they will reimagine what governance might look like, they will follow new logics of what marriage and building a family can feel like. The kingdom people are widely progressive, while also being steadfastly traditional by living close to the land and to each other.

Luella’s section is where avid readers find their literary rewards. We see the importance of words themselves. Luella turns language around and tastes it, like fruit from her own garden. “Suggest. What a pretty word,” says Luella, musing on what it means to be able to consider her actions, rather than be forced. Suggest is freedom, she realizes. Freedom means having choices.

the kingdomfolk are kin to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s People of Maconda. As in his “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” family is at the root of community — but it’s not a nuclear family. Here a husband might support his wife’s ex-husband, knowing him as brother. Here a father-in-law loves like a father. Here a woman can live in her own house, by herself, and thrive. The women do work that feels meaningful to them. The men play with the children in ways that also teach.

Both sections are written in first person. Nikki’s voice is matter of fact, focusing on what she sees and knows. She reveals herself to be a bird watcher, at one point longing for binoculars to see better ― a metaphor for coming to see, as in understand.

Luella’s sections lean poetic and focus on what she feels. Emotional attachments drive her section — her romantic love, her motherly love and even her love of her father and best friend. This love of people comes into conflict with her love of the land, driving a number of the book’s conflicts.

As the novel goes on, these two sections collide thematically, contextually, and over language. Luella and Nikki both find themselves falling in love unexpectedly; grappling with the challenges of having a grown daughter; fighting for land, the same exact land, it turns out; and having to face real life sacrifices as they work within the American legal system historically used against them. Nikki, the woman who once read books for the pictures, becomes curious about the power of words. When she hears “intentional communities,” she thinks, “That’s an interesting phrase.”

Nikki comes to understand that land and people are in a messy and necessary relationship of care with each other. While the book has an uplifting message, reading it is an act of grieving.

African Americans lost more than $326 billion in land wealth between 1910 and 1997. If we include the people of African descent native to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where both Kurt Marsh Jr. and I are from, the number rises billions more. I no longer have claim to my family’s historic land. And yet, the land does call me home. I read “Happy Land” in grief, but also, I have to say, with hope.

Tiphanie Yanique is a Townsend Prize nominee for her 2021 novel “Monster in the Middle.”

FICTION

Dolen Perkins-Valdez

Penguin Random House

368 pages, $29

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured