A few years ago, crime novelist Wanda Morris was absent-mindedly folding laundry with the news on in the background when a story caught her attention

“A woman’s house and property were damaged by Hurricane Florence, but the woman couldn’t get any assistance from FEMA because she couldn’t prove she owned her home,” Morris recalls. “It had been handed down to her from her great-grandparents, and she had always lived there, but there had been no will or deed. That woman haunted me, and that story stuck with me. I wondered how many other people were in a bind like that. It struck me as a travesty of justice.”

Closer to home, she wondered how many in her Geechee-Gullah community might be affected. Morris had practiced corporate law, but estate planning was outside her area of expertise, so she did a little digging on the legal theory of “heirs’ property” — a loophole in the legal system big enough for bulldozers to plow through it.

It refers to houses and land that pass from generation to generation without a legally designated owner, resulting in fractured ownership divided among several living descendants in a family. If a developer can convince just one heir to sell their share of the property, it can force a court-ordered partition sale of the entire property, even if the other fractional owners oppose it — even if a householder gets kicked out on the street. Heirs’ property is a mechanism for the most rapacious form of gentrification, in other words, and you can guess who loses.

“People affected tend to be land-rich but cash-poor, without ready access to tax- and estate-planning services,” says Morris, who lives in Atlanta. “It’s a huge problem for Black and brown communities and poor, white Appalachian communities. In Lowcountry regions of the South, most heirs’ property was acquired by Black Americans after Emancipation. Land that had once been deemed undesirable because of its mosquito-infested marshlands is now in high demand by developers.”

Beloved ancestral homeplaces, with their bottle trees and doors painted “haint blue,” are giving way to luxury beach-side resorts for pennies on the dollar.

“The end result is the loss of generational wealth,” Morris says. “An estimated $30 billion of generational wealth is lost each year in Georgia alone because of heirs’ property laws.”

That’s big money. Land, inheritances — people have been murdered for less. Morris saw a ready-made narrative plot.

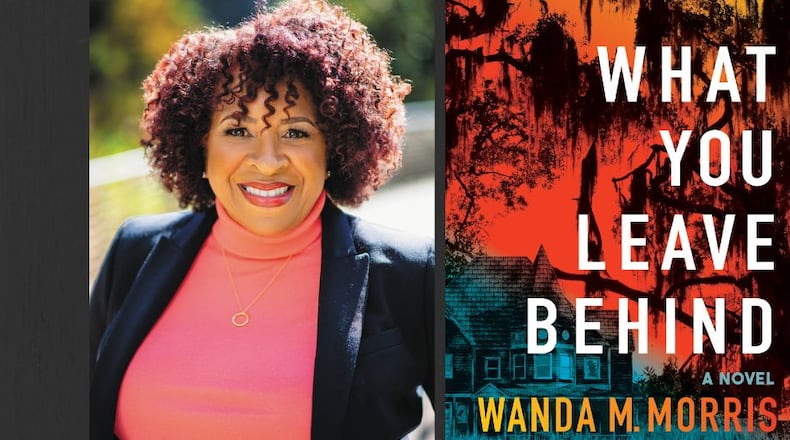

It takes a deft writer to craft a suspenseful page-turner ostensibly about real estate, but she proves up to the task in her third novel, “What You Leave Behind” (HarperCollins, $30), set in Brunswick and rich in lively characterizations. Morris has created her own beguiling form of magical realism as a chorus of Geechee-Gullah ancestors narrates each chapter in their patois to numinous effect, and benevolent haints lend a helping hand in crime-solving. It is a lyrical document of a vibrant culture as well as an exposé of real-life shady business practices. Honor your ancestors, goes the lesson, and they will protect you.

“I needed what the old folks used to call a ‘dayclean.’ A new day. A fresh start,” muses the heroine who leaves her Atlanta law practice to return home to the coast, where trouble awaits.

Morris says, “I wanted to write about a woman just trying to live her life with all of her little secrets, and I wanted it to be entertaining, but I also want to speak to what is going on in the larger world around her. I wanted to lift up the issue of heirs’ property and shine a light on what is essentially a crime in plain sight where the only people who benefit are the unscrupulous people with means.”

“De land we; we de land,” goes the expression of a people deeply rooted in a place draped in Spanish moss.

The author, who writes under the name Wanda M. Morris, was born far away from the coast in Cleveland, Ohio, the youngest of seven. The daughter of a janitor and a nurse, she was the first in her family to attend college. “I was that kid with her nose in a book, curled up in a nook of the library,” she says. “My mother was of Geechee-Gullah descent and was very big on the interpretation of dreams.”

She was conscious of a lack of cultural representation in literature early on. “Dick and Jane didn’t look like me,” she says, “But I stumbled onto Toni Morrison. I must have been in the sixth grade when I read ‘Sula’ and ‘The Bluest Eye,’ and those books changed my life. From there I went on to Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston.” The she “landed” in suspense stories and devoured Dashiell Hammett. “I liked figuring out the puzzle aspect of mysteries.”

She attended Case Western Reserve University and earned a degree in accounting. She crunched numbers for a while before going back to her alma mater for law school. A job at a law firm brought her to Atlanta after she graduated. “My first week on the job, I met a boy, and we’re still going strong 30 years and three kids later,” she says.

She practiced law at several Fortune 500 companies, but the itch to write never left her. “I kept tamping it down and tamping it down, and finally I had to write,” she says. Morris’ debut novel, the legal thriller ‘All Her Little Secrets,’ won instant acclaim. It was the No. 1 Top Pick for “Library Reads” by librarians across the country, and it has been optioned for a limited series, starring and executive produced by three-time Emmy winner Uzo Aduba. (Morris will serve as an executive producer.)

The late-blooming author joined Atlanta’s Sisters in Crime group, where she found helpful mentors.

“I have to admit that at first, I was like, ‘Who is this lady writing about Atlanta? That’s my town,’” says thriller maestra Karin Slaughter. “Then I read her first book, and it was a revelation. Wanda’s not just an excellent storyteller, she’s a very good writer, and you can feel her legal brain at work as she’s crafting the plots because they’re so tightly drawn. There are no holes, which is really hard to do. You’d never guess that she hasn’t been writing for years because she avoids all the rookie mistakes. You know who to root for and who needs to get punished for their dastardly deeds.”

Morris is not limited to thrillers. Her second novel, ‘Anywhere You Run,’ is literary fiction set in the Jim Crow South and follows the peripatetic lives of two sisters after the murder of a white man in Mississippi. Kathy Hogan Trocheck, who writes under the name Mary Kay Andrews, will moderate the book launch for ‘What You Leave Behind’ on June 18 at The Georgia Center for the Book in Decatur.

“Sinking into the latest Wanda Morris thriller is a guilty pleasure,” Trocheck says. “I loved her latest book, not just because this year we both chose to write about the same patch of Coastal Georgia, but because she sees this landscape through an entirely different prism. This is a pulse-pounding thriller with a heart and a social conscience, but then, that’s what makes a Wanda Morris novel so irresistible.”

Morris is already hard at work on a fourth novel. “This time, I’m questioning why we don’t put children front and center in our priorities,” she says. “I don’t want only to entertain with my books. I hope they will somehow help somebody, too, in their real lives.”

AUTHOR EVENTS

Wanda M. Morris. In conversation with Mary Kay Andrews for the book launch of “What You Leave Behind,” presented by the Georgia Center for the Book. 7 p.m. June 18. Free but registration required. Decatur Library, 215 Sycamore St., Decatur. georgiacenterforthebook.org.

Additional events:

1 p.m. June 22. Free. FoxTale Book Shoppe, 105 E. Main St., Woodstock. foxtalebookshoppe.com

7 p.m. June 26. $5. Atlanta History Center, 130 W. Paces Ferry Road, Atlanta. www.atlantahistorycenter.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured