Opening my copy of the new “Lebanese Cuisine” by Madelain Farah and Leila Habib-Kirske (Hatherleigh Press, $25) unleashed a flood of memories. There were recipes for dishes I hadn’t made in many years — triangle meat pies, raw kibbi, rice cooked with vermicelli, stuffed squash and small eggplants, green bean stew with cubes of lamb. So many dishes I watched my second-generation Syrian mother and her sister prepare in one kitchen or another, but recipes never written down and so lost in time. My mother and my Aunt Lily were of a generation that added “a pinch of this” and “a little of that” and cooked until something looked or smelled right, preparing dishes they had watched their own mother make.

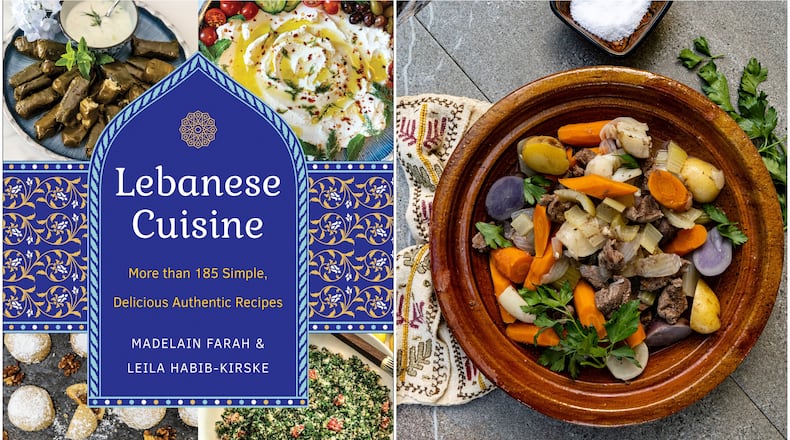

I immediately read the book from one end to the other. Daughter Habib-Kirske wrote the book to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the original publication of her mother Farah’s “Lebanese Cuisine.” The original spiral-bound cookbook published in 1972 resonated with others who needed guidance to cook the dishes of their heritage and sold more than 100,000 copies in its first 30 years.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

Syria and Lebanon share a border and many elements of their cuisine, so the dishes in the book are generally interchangeable with those of my childhood. It’s food that is often vegetable-forward and, like other dishes prepared around the Mediterranean Sea, there’s liberal use of olive oil and plenty of legumes like lentils and chickpeas. Habib-Kirske modified some of her mother’s recipes to reflect today’s farm-to-table and local produce movements by including things that weren’t as available in the ‘70s like purple potatoes, and substituting Swiss chard where my mother might have used frozen spinach.

Happily for me, with the arrival of this book, many dishes are now back in my dinner rotation. I’m planning meals centered around Lahm Miswi (grilled kebabs of lamb or beef) and Shaykh al-Mihshi (rounds of eggplant stuffed with ground lamb and pine nuts). I’ll be making Lifit Makbus (pickled turnips) like the ones my mother loved. Just sounding out the Arabic names takes me back to my childhood, where the only Arabic spoken was the names of the dishes we were eating.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

My mother only made a few Syrian pastries, but my Lebanese godmother would prepare platters of sweets. I have struggled for years to replicate her recipe for Ma’mul, a nut-filled pastry made with farina (farina is sold at the grocery store as Cream of Wheat cereal). The handwritten recipe card disappeared and, after trying every recipe in the dozen Syrian cookbooks in my collection and recipes found online, I think the one from this book finally reproduces the pastries I remember from my childhood.

RECIPES

We’ve adapted three recipes from “Lebanese Cuisine” by Madelain Farah and Leila Habib-Kirske (Hatherleigh Press, $25): a lamb stew that’s very vegetable-forward, leaves of Swiss chard and cabbage stuffed with rice and chickpeas as a vegan alternative to using ground beef or lamb, and nut-filled pastries.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

Yakhnit at Khudar bil-Lahm (Lamb-Vegetable Stew)

This stew is an example of how author Leila Habib-Kirske updated a traditional recipe to reflect new ideas of cooking. Growing up, I never saw a purple potato in our kitchen, but their addition to this recipe results in a colorful stew that’s almost the definition of today’s healthy eating mantra, “eat the rainbow.”

Recipes adapted from “Lebanese Cuisine” © 2023 by Madelain Farah and Leila Habib-Kirske. Reproduced by permission of Hatherleigh Press.

Credit: CHRIS HUNT

Credit: CHRIS HUNT

Mihshi Waraq Silq or Malfuf biz-Zayt (Stuffed Swiss Chard or Cabbage Rolls)

You can make this recipe just with Swiss chard or just with cabbage, but we had both on hand and liked the contrast in textures between the rolls. Chopping the chickpeas is not required, but makes the filling easier to roll.

Grains of rice will escape from the rolls as they are cooking. Taste them to tell if the rice is done.

Credit: CHRIS HUNT

Credit: CHRIS HUNT

Ma’mul (Nut-filled Pastry)

This recipe shapes the pastries by hand, although they are traditionally made using a carved wooden mold, which produces a ridged pattern that holds powdered sugar perfectly.

Sign up for the AJC Food and Dining Newsletter

Read more stories like this by liking Atlanta Restaurant Scene on Facebook, following @ATLDiningNews on Twitter and @ajcdining on Instagram.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured