DeKalb CEO explores Oglethorpe’s anti-slavery stance in new biography

When Michael L. Thurmond, CEO of DeKalb County, served on the Georgia’s James Oglethorpe Tercentenary Commission in 1996, he was part of a delegation that visited Oglethorpe’s grave in Cranham, England. A large white marble plaque was inscribed, in part, “He was the Friend of the oppressed Negro.”

This surprised Thurmond; even though he knew some about Georgia’s founder, he had never heard him described in such terms, and his new biography, “James Oglethorpe, Father of Georgia,” sprang from his resulting curiosity. Was the founder of one of the Confederate states “woke?” (A term Thurmond never uses.)

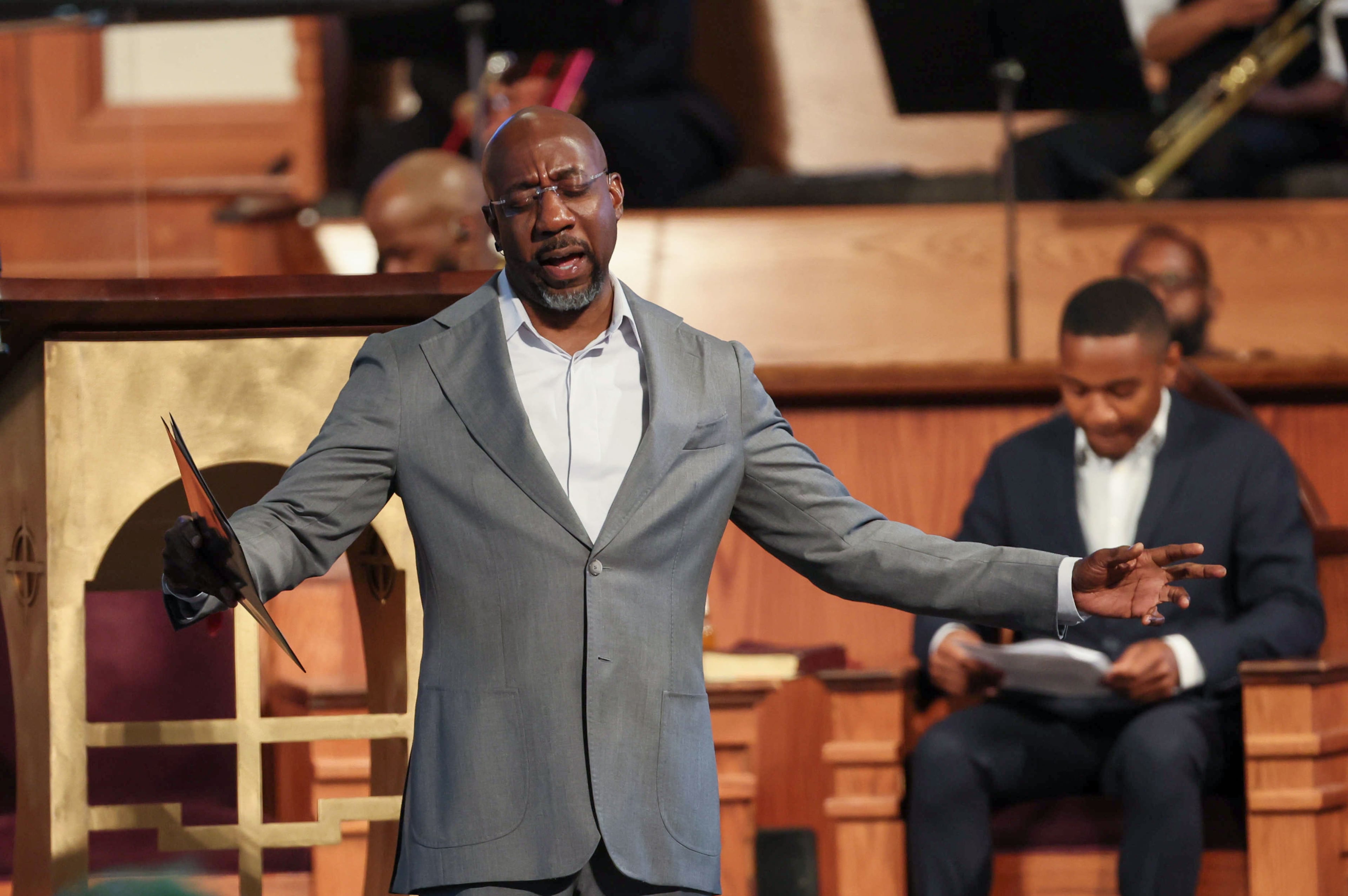

Thurmond isn’t just a politician but a true student of history. He is a lecturer at the University of Georgia’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government and is the author of two previous books of local history, one of which, “Freedom,” was listed in 2004 as one of the “25 Books All Georgians Should Read” by The Georgia Center for the Book. He is also the great-grandson of Harris Thurmond, who was enslaved on a plantation in Oconee County.

Although other historians have written about Oglethorpe’s anti-slavery leanings, Thurmond wants to establish the state founder as enlightened for his time and someone we can look to today “to chart a more inclusive and progressive course.”

Oglethorpe was born in 1696 to a wealthy and influential family in Surrey. He attended Eton and Oxford and was elected to the House of Commons at age 26. There he met Thomas Bray, a clergyman with enlightened (for the time) racial views.

The two men envisioned a debtor’s colony in the New World, where Brits in debtor prisons could start over as farmers and tradesmen. But competing against enslaved people who work without compensation would make it economically difficult for the whites to establish themselves.

Thus did the colony of Georgia forbid slavery, but mainly out of expediency and only a little bit out of morality.

Oglethorpe at the time was not so much anti-slavery as we would frame it, but more willing to think differently from nearly everyone else in the power structure, and Thurmond gives him credit, calling the plan a “radical departure” from the norm. He points out that during this period, freedom was the true “peculiar institution” and various forms of chattel slavery, serfdom and indentured servitude more the standard.

Oglethorpe sometimes referred to his swampy outpost in the New World as “American Zion,” not in any official sense but in the Old Testament sense of a kingdom of heaven on earth.

In 1732 King George II granted Oglethorpe and other trustees a charter for what would become the state of Georgia. That same year, Oglethorpe severed his ties with the Royal African Company, a notorious British slaving enterprise from which he had profited. Thurmond frames that inflection point as an early and crucial step on his journey from slave trader to abolitionist.

From the beginning, however, enslaved Blacks were put to work in Georgia, and never mind the law. Oglethorpe himself looked the other way, especially when there was hard work to be done.

Then, in just a few short years, some of the white settlers decided that they would like to own enslaved Africans after all, touching off a period of political jockeying between pro- and anti-slavery forces.

Oglethorpe left Georgia to return to England in 1743, facing a court martial on trumped up charges (he was acquitted), never to return. By 1751, slavery had been legalized in Georgia and the number of enslaved Blacks began to increase. Oglethorpe’s dream of Zion had lasted less than 20 years, and Georgia would stay a state that allowed slavery until 1865.

We tend to think of abolitionists mainly as 19th century New Englanders, but England had a strong abolitionist movement that was notching successes in the fight against slavery decades earlier.

Oglethorpe came to deplore slavery gradually over his lifetime, similar to Abraham Lincoln’s journey more than a century later. He was aided by friendships with two formerly enslaved Black men: Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, a Muslim African who wrote and spoke eloquently against slavery in 18th century England, and Olaudah Equiano, an emancipated African slave who wrote an early account of the Middle Passage.

By midway in the book, Oglethorpe is dead and the story of Georgia’s founding is over, but Thurmond continues to tell Georgia’s story up to 1865 through the prism of slavery. These latter chapters can get tedious, although the section on Sherman’s March to the Sea is quite strong, told mainly from the point of view of exuberant Blacks rather than aggrieved whites, as is more often the case.

In many best-selling popular histories (think Doris Kearns Goodwin, David McCullough or Stephen Ambrose), the authors recreate detailed scenes that transport the reader back, and their books as a result are frequently more enjoyable. Thurmond, with limited source material, mostly puts his head down and presses on, and the result is a book to admire even if it is not always a book to savor.

But it is nonetheless a welcome addition to the bookshelf of any serious student of Georgia history, or even as an eye-opener to anyone who drives past his namesake university in northeast Atlanta and has any curiosity about the man who started the road to the city we now call home.

NONFICTION

“James Oglethorpe, Father of Georgia”

By Michael L. Thurmond

University of Georgia Press

241 pages, $29.95