Clark University professor Daniel Black’s latest novel is a tender coming-of-age story about growing up Black and queer and ultimately wringing some grace from a harsh upbringing. “Isaac’s Song” will speak to anyone who ever chafed under a strict disciplinarian.

Isaac Swinton is expressive and artistic — a fabulous and ingratiating scamp — but his father Jacob is an old-school patriarch from backwoods Arkansas who metes out blow after blow, literal and figurative, in a futile effort to mold a more conventional man out of a son who “runs like a girl.”

At one point, Isaac tries on his mother’s clothes and jewelry: “He grabbed my fragile little shoulders and shook me until the earrings tumbled to the floor,” Black writes. “‘Is you done lost yo mind, boy!’ he yelled. … Suddenly my left cheek burned and trembled. I didn’t realize, for several seconds, I’d been slapped. … I wanted him to love me, and I thought that if I were beautiful maybe he would.”

With every confrontation, your heart aches for Isaac, but Black’s magnanimous writing ultimately fosters sympathy for Jacob, too, and anyone miserably caught up in a prescribed societal role. With great gentleness, Black reveals the macrocosmic levers behind the fraught dynamics at this family’s dinner table.

“His father is trying to prepare him for the world by toughening him up,” Black says, “but that can be hard to recognize as love. There are many forms of love, and sometimes it takes a form a child might miss.”

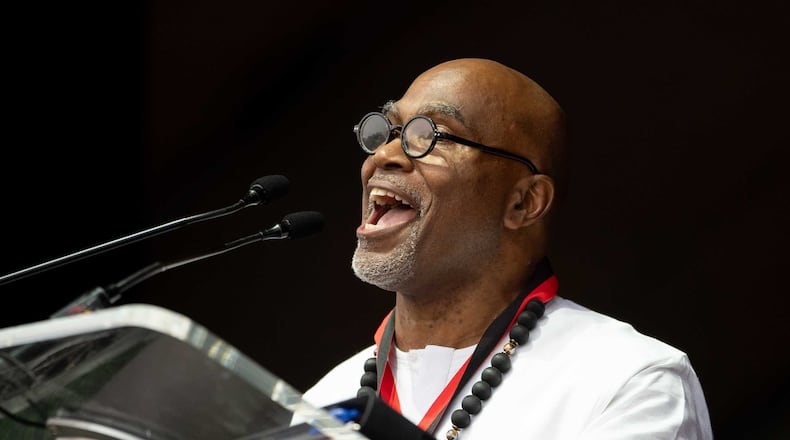

Black, 59, is a popular professor of African American studies. This novel is his eighth book exploring themes of racial tensions and sexuality. His other volumes include “The Coming,” “They Tell Me of a Home” and “Don’t Cry for Me.” He won a Georgia Author of the Year award last year for the essay collection “Black on Black,” and “Perfect Peace” was chosen as the 2014 selection for “If All Arkansas Read the Same Book” by the Arkansas Center for the Book.

Alice Walker said of his oeuvre that it is “flawlessly faithful to the language of ancestors who grappled as best they could with more than they could ever understand.”

“Children are central to my work,” Black says. “I write about the traumas of Black children. And I’ve been a church musician since I was 5, so there is always music in my texts.”

“Isaac’s Song” originally was developed as an epistolary novel told through letters exchanged between Jacob and Isaac. “But Isaac’s voice was getting lost, so after I finished it, I started over and completely rewrote it,” says Black.

“Don’t Cry for Me” retains the letter-writing format and tells Jacob’s story; his son’s story is told in “Isaac’s Song.”

Calling it Black’s “most healing and cathartic novel to date,” his editor at HarperCollins, John Glynn, describes “Isaac’s Song” as “a piercing, resonant and hopeful novel about a young man on a universal quest to make peace with his past and find his way back to himself,”

Black, who has an outsize personality and went viral last year on YouTube for his rousing commencement speech at Clark Atlanta University, concedes the novel is about “30% autobiographical.”

He grew up in Blackwell, Arkansas. His father was a farmer and mechanic with a “third- or fourth-grade reading level,” and his mother was a homemaker.

“It was extraordinarily rural — we’re talking wells and outhouses into the 1970s,” he says, “Yes, there was some discrimination, but it was not a bastion of oppression as you might think. I was very outgoing, and my white teachers were kind to me, particularly Ms. Crowfoot, who critiqued my writing hard and got me prepared for college.”

Black was close to his great-grandmother, a teacher. “She went blind, so I would read the Bible and Reader’s Digest to her. I became her eyes. That’s where I got my love for the written word.”

He enrolled at Clark University and became an enthusiastic proponent of the HBCU experience, which he extols in “Isaac’s Song.”

“It opened me up to books and ideas, stretched and expanded me, introduced me to other ways of knowing God, other ways of loving,” he says. “The world is so much bigger than rural Arkansas. Whatever you think of God and the world, it’s 10 times bigger!”

Black graduated in 1988 and left for a yearlong program of British literature at the University of Oxford, then returned to Temple University, where he earned a Ph.D. in American literature studying under Sonia Sanchez. In 1993, he joined the faculty of Clark, where he established Ndugu Nzinga — it means brotherhood and sisterhood in Swahili — an organization that uses African culture and traditions to guide character development. He is as interested in the soul as he is the mind.

“Atlanta lives up to its hype as the so-called Black mecca,” the author says. “It’s that rare place where you can experience high Black culture but also taste the Southern experience.”

La’Neice Littleton was a student who became a protégé. She now works as a public historian at the Atlanta History Center. “Dr. Black is a humble, generous, magical man who I consider my primary spiritual adviser,” she says. “One thing he taught me was that we all get our lessons, sooner or later. Whether I was facing a challenge or a triumph, he would always say, ‘What’s the lesson here?’ He also taught me that it’s never too late to begin the healing process.”

Another mentee, minister Brian Long, says, “You don’t have to be an African American male to relate to Dr. Black’s work. I am Isaac. If people look deep within themselves, they’ll see that they are Isaac, too. This book is a very accessible, very American story. It’s a healing book. In these divisive times, if people will just read this book, it will restore something in them.”

The young protagonist of “Isaac’s Song” rebounds from his bruises by putting pen to paper and finds his voice.

“Another of my themes is freedom, liberation,” Black says. “When one gets to a place of being unconcerned with others’ reactions to his truth, that is freedom. Art is a medium with which freedom can be achieved. It forces people to imagine what the truth would look like if it weren’t worried about. Isaac finds his voice as a writer, and that is his liberation, discovering what freedom looks like, what it tastes like. It will free others around you, too, including your father, if you’re bold enough to write your truth.”

Even an iron fist, in Black’s fiction, can open for an olive branch.

AUTHOR EVENT

Daniel Black. The author discusses and signs copies of “Isaac’s Song.” 7 p.m. Jan. 16. Book purchase required for admission. Eagle Eye Book Shop, 2076 N. Decatur Road, Decatur. 404-486-0307, eagleeyebooks.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured