Cathy Hughes changed Atlanta radio and is still building her own legacy

Cathy Hughes always wanted to “get into the Black people business.” Looking at her career today, it’s clear the Nebraska native not only secured a place in the history of American broadcasting, but also had an outsized impact on the business of Black entertainment in Atlanta.

Her company, Urban One, Inc., is the largest Black-owned broadcast conglomerate in the U.S., distributing content targeting Black audiences. Rebranded from Radio One in 2017, Hughes still serves as chairwoman of the corporation, which has grown to include the cable networks TV One, CLEO TV, media syndication company Reach Media and iOne Digital, which operates a number of popular websites including Bossip, NewsOne and others.

“African Americans have embraced us and our concept for establishing a communications corporation that was going to give their stories and viewpoints correctly,” Hughes said.

In July 1995, Radio One acquired its first radio station in Atlanta: WHTA-FM, a.k.a. Hot 97.5. It was the city’s first hip-hop station, and where entertainers Christopher “Ludacris” Bridges and LaLa Anthony started out as interns before becoming on-air talent, and going on to becoming household names.

Six years later, WHTA-FM became Hot 107.9, retaining its core urban hip-hop and R&B format. Radio One went on to own three more stations in Atlanta: Majic 107.5, Praise 102.5, and Classix 102.9.

“When Hot 97.5 came out, the culture shifted,” said former Hot 107.9 personality and Atlanta native Brian “B-High” Hightower. “The on-air talent on 97.5 and 107.9 sounded like us, and the music they played was amplifying the city. It was the gift that kept on giving.”

Hot 107.9 launched other hip-hop notables like DJ Drama and Ludacris’ manager Chaka Zulu, before they embarked on successful careers in hip-hop.

“It was like a feeder program that gave all of us our chops,” Hightower said.

Born in Omaha, Hughes moved to Washington, D.C., in 1971, where she became a lecturer at Howard University’s school of communications, which had only recently launched when she arrived. She said relocating gave her the confidence and access she needed to pursue opportunities, and to create them.

“I’d grown up in a cultural desert,” Hughes, now 76, said. “I used to write to my mother and tell her I was afraid I needed to go to see an optometrist because my eyes were so tired from staring. I was amazed to be in a city where there were African Americans on television and the radio doing exciting things.”

As Howard’s communications department grew, so did Hughes’ desire to join WHUR, the historically Black college’s station.

She became sales manager in 1973 and was promoted to general manager two years later, becoming the first woman to run a broadcast facility in the nation’s capital. There she began to realize connecting with listeners means offering relevant programming.

In 1976, while at WHUR, she said she came up with the idea for “the Quiet Storm,” a weekend show that played a rotation of ballads and love songs by Black recording artists. The new format’s late airtime became a staple at Black radio stations nationwide.

Hughes credits the Black LGBTQ community for embracing it early on, and said she created the show to provide entertainment for students who did not have dates or preferred to stay home as opposed to going to hang out. “It was basically Black elevator music that is relationship-focused, and the popularity started to blossom,” she said.

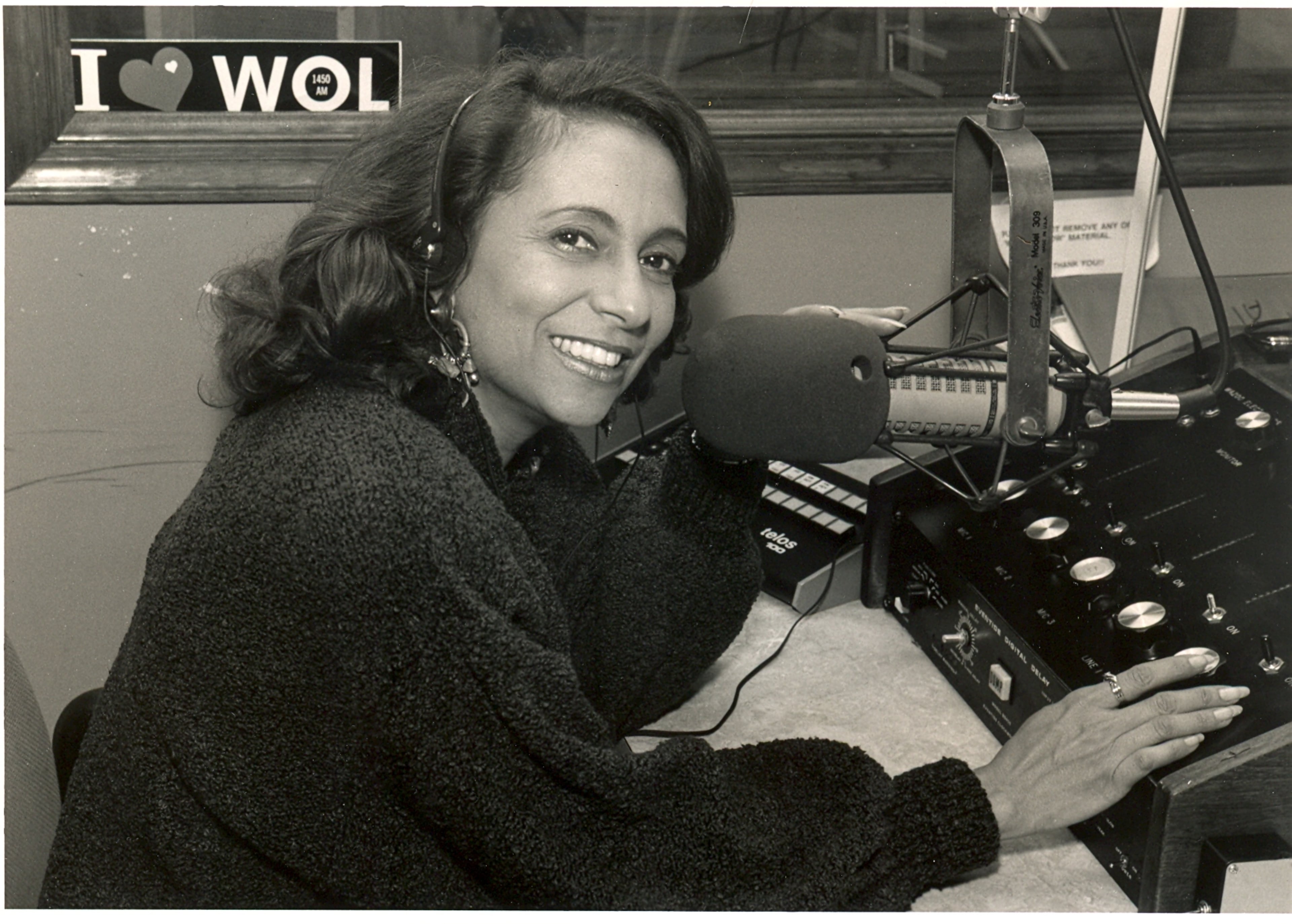

She left WHUR to lead another D.C. radio station, WYCB, in 1978. Two years later, she purchased her first radio station, WOL-AM, in Washington, D.C., after being turned down by 32 lenders.

It was part of Radio One, the parent company she founded the same year, which now owns and operates 57 stations in 15 markets.

Despite her innovation, the station wasn’t generating any revenue. She was forced to live at the station with her son, Alfred Liggins, who she birthed when she was 17 years old. They later relocated to a trailer near their office in a drug-infested neighborhood.

Hughes says making the station her temporary home was no different than other cultures who live in apartments above their businesses.

“Sometimes, you have to be uncomfortable doing things that you’re not sure about in order to get to the next level,” Hughes said.

In 1986, Hughes created “The Cathy Hughes Morning Show,” a daily talk radio program that pioneered reporting news on-air from a Black perspective. A year later, Hughes and Liggins, who joined the company’s sales department in 1985, took WTKS, an AM soft rock station, and turned it into WMMJ.

Becoming Urban One’s first profitable station, WMMJ Majic 102.3 and 92.7 was responsible for urban adult contemporary, a format created by Hughes and Liggins that combined classics with current hits.

Toni Judkins, TV One’s former executive vice president of original programming and production, was responsible for helping the cable network create different genres of shows. Now senior vice president of programming and development for Hallmark Media, she credits Hughes’ innovation with creating radio formats for guiding her career.

“We had a responsibility to represent all aspects of the Black experience,” Judkins. “It’s about taking those trends and translating them for our community.”

By 1991, Hughes created the Stone Soul Picnic, a concert series that brought veteran acts back to the stage. Going out into the community and training Liggins to run the business began to raise Hughes’ profile as a Black and woman entrepreneur.

“The company was so successful because he [Alfred] grew up in the station watching me,” she said. “He was fearless and bold. The Harvard Business School turned us into a case study because our little AM and FM were the tweety birds that could. People used to tease us about having to drive to other places, but we were competing against big signals.”

Hughes stepped down as CEO of Radio One in 1997 and appointed Liggins as CEO. He put the corporation on the New York Stock Exchange, which made Hughes the first Black woman to head a publicly traded company.

Honored with both a street in Omaha and Howard University’s School of Communications being named in her honor, Hughes also became the first Black woman radio inductee in the Broadcast Hall of Fame in 2019.

She’s not done yet. Hughes wants to produce a feature documentary on the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, her trombonist mother’s racially integrated swing ensemble featuring 18 women that performed throughout the 1930s and early ‘40s. The project, she believes, is another opportunity to remain committed to her mission.

“Building generational businesses is difficult, and it’s particularly hard in the African American community,” Hughes said. “We have too many examples of the parent generation not preparing a succession plan. We want to be able to be around and have some little Black children look up at a sign and see we were established in 1980 in 2080.”