Bookshelf: More than a drag queen, Charlie Brown was an activist

Mr. Charlie Brown was an Atlanta treasure, and he had the prestigious Phoenix Award to prove it. But the road this audacious, foulmouthed drag queen took to arrive at that destination required barreling through a lifetime of roadblocks.

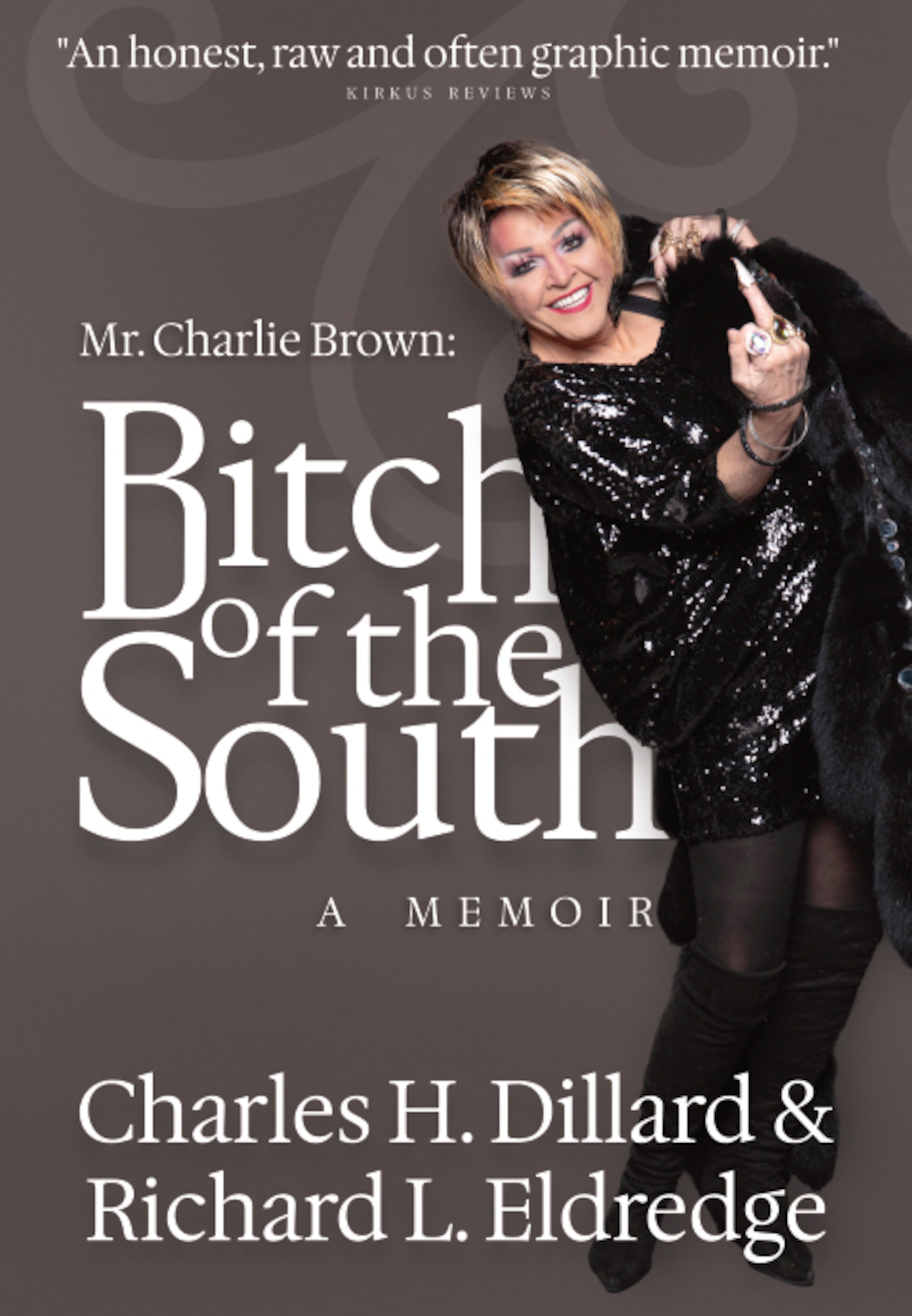

His life story makes for fascinating reading in the new memoir, “Mr. Charlie Brown: Bitch of the South” (Ardmore Avenue Publishing, $39.99), told in his own voice with a big assist from Richard Eldredge, a former reporter for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and editor of Eldredge ATL, who started a publishing company to bring the book to market.

The memoir leaves little to the imagination. It’s got drugs. It’s got sex. But that’s just a small part of it. The book beautifully captures the classic Horatio Alger-style story, only this one has sequins and fake breasts made out of pantyhose and oatmeal.

Those who only knew him as the longtime emcee and impresario of Charlie Brown’s Cabaret at the fabled 24-hour disco Backstreet, may be shocked to learn that Charles H. Dillard was born to a Baptist missionary and grew up on a farm in rural Tennessee. It was there he first discovered his love of pageantry with the color guard for the high school marching band.

During the Vietnam War, he would volunteer for the Air Force and do basic training in Texas before he was kicked out for “conduct unbecoming an officer” for being gay.

He landed in Nashville, Tennessee, and worked as a hotel desk clerk, where he got his nickname, and he began to live openly as a gay man. It’s also where he first performed in drag.

“Despite the risks associated with publicly running around with a bunch of queers, I needed to be true to myself,” he writes. “But the biggest problem associated with flaunting your homosexuality at that time? It was still classified as a mental illness. In Nashville, I was living so openly my friends feared I’d be put in a mental institution.”

Brown proceeded to live the life of a nomad for years, bopping around the Southeast getting jobs performing drag and developing his act.

“My Charlie Brown stage persona developed slowly over time. It was this fearless persona I slipped into on stage. When I hit that stage, all of my self-doubt vanished. I was invincible. Charlie Brown protected Charles Dillard when he was up there in a wig and heels.”

Although quite beautiful in his youth, Brown’s drag persona was more comedic than glamorous. Among his signature numbers were “9 to 5″ as Dolly Parton and “The Rose” as Bette Midler. As an emcee his specialty was crowd work, specifically targeting straight women in the audience. And at Backstreet, he was famous for his nightly show closer, an impassioned monologue about the rights of LGBTQ+ people to live freely out in the open. It was a struggle about which he knew a thing or two.

“God put us all on this Earth. If he had wanted us all to be straight, we’d all be straight. If he wanted us all gay, we’d all be gay. Who are we to judge his creations?” he’d proclaim, while his audio technician, Fred Wise (Brown’s beloved husband and life partner for 45 years), played Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” in the background.

It may come as a surprise that one of the barriers Brown broke down was within the gay community. Throughout the ‘70s, drag queens were personas non grata at the Atlanta Pride Parade.

“As Charlie says, it was a bunch of white guys in Izod shirts with popped collars,” said Eldredge. “They wanted this white male aesthetic on the evening news.”

But in 1980, “he made history as the first drag queen in the parade,” said Eldredge. “Then the AIDS crisis comes along and the drag performers were the ones raising money for AID Atlanta and all the other AIDS service organizations. The Pride committee recognized what a value these drag performers were. … Now when you look at the parade, it’s just a rainbow, and Charlie helped make that happen for drag performers.”

Eldredge first met Brown in 1994 when he interviewed him in the dressing room at Backstreet for Southern Voice (now Georgia Voice), and the performer became a frequent source over the course of Eldredge’s journalism career. It was during an interview for a story Eldredge was doing for Atlanta magazine when the idea for the memoir arose.

For eight months during the coronavirus pandemic, they talked on the phone every week. Then Eldredge would transcribe the recordings, massage them into a narrative and share the chapters with Brown and Wise for finessing.

Eldredge wasn’t sure there would be interest in Brown’s story outside the LGBTQ+ community, but it has universal appeal. Not only is it an inspiring rags-to-riches story — if not in the monetary sense, then in terms of success and fame — but it also records for posterity a significant part of Atlanta history, including the effects of the AIDS crisis.

“Charlie was a member of a generation that was decimated by a plague and there aren’t that many members of Charlie’s generation that made it through,” said Eldredge. “Charlie buried so many of his friends and fundraised for so many of his friends. I knew that Charlie represented a generation that had largely been silenced.”

Following a series of health issues, Brown died in March 2024, so he didn’t get to see his book make it to publication. But he received a bound copy of the completed manuscript last year and he couldn’t have been more pleased, said Eldredge.

One of the most poignant moments in the book comes at the end and was a late addition. Last year, Brown was driving up Buford Highway in full drag on his way to a gig when he had a minor automobile accident. When the police officer came on the scene to take a report, the first thing he did was ask Brown for his pronouns. I can’t think of a better testament to the work Brown did to foster acceptance and respect for all.

Eldredge will be outside Atlanta Eagle (1492 Piedmont Ave. NE) selling copies of “Mr. Charlie Brown: Bitch of the South” during Atlanta Pride, Oct. 12-13.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She may be reached at Suzanne.VanAtten@ajc.com.