Bookshelf: Local author considers the politics of public pools

Like many middle-class white kids who grew up in the suburban South in the ‘60s, my family employed a Black housekeeper, although “maid” was the word we used back then. Her name was Mae, and one summer she accompanied us to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, for our annual vacation.

One night after supper, my father and Mae got in the car and I asked to ride along, having no idea where they were headed. After driving up the coast a bit, we arrived at the community of Atlantic Beach. It looked a lot like our little corner of the Grand Strand. It had a sandy beach lined with stilt houses and a small, crowded commercial district with an arcade and some amusement rides. The only difference was, every person in sight was Black.

After we dropped Mae off for her night on the town, I asked my father why she didn’t just go to our beach. He told me she’d have more fun with people who looked like her. That may have been true, but that wasn’t the real reason: Beaches across the South were segregated.

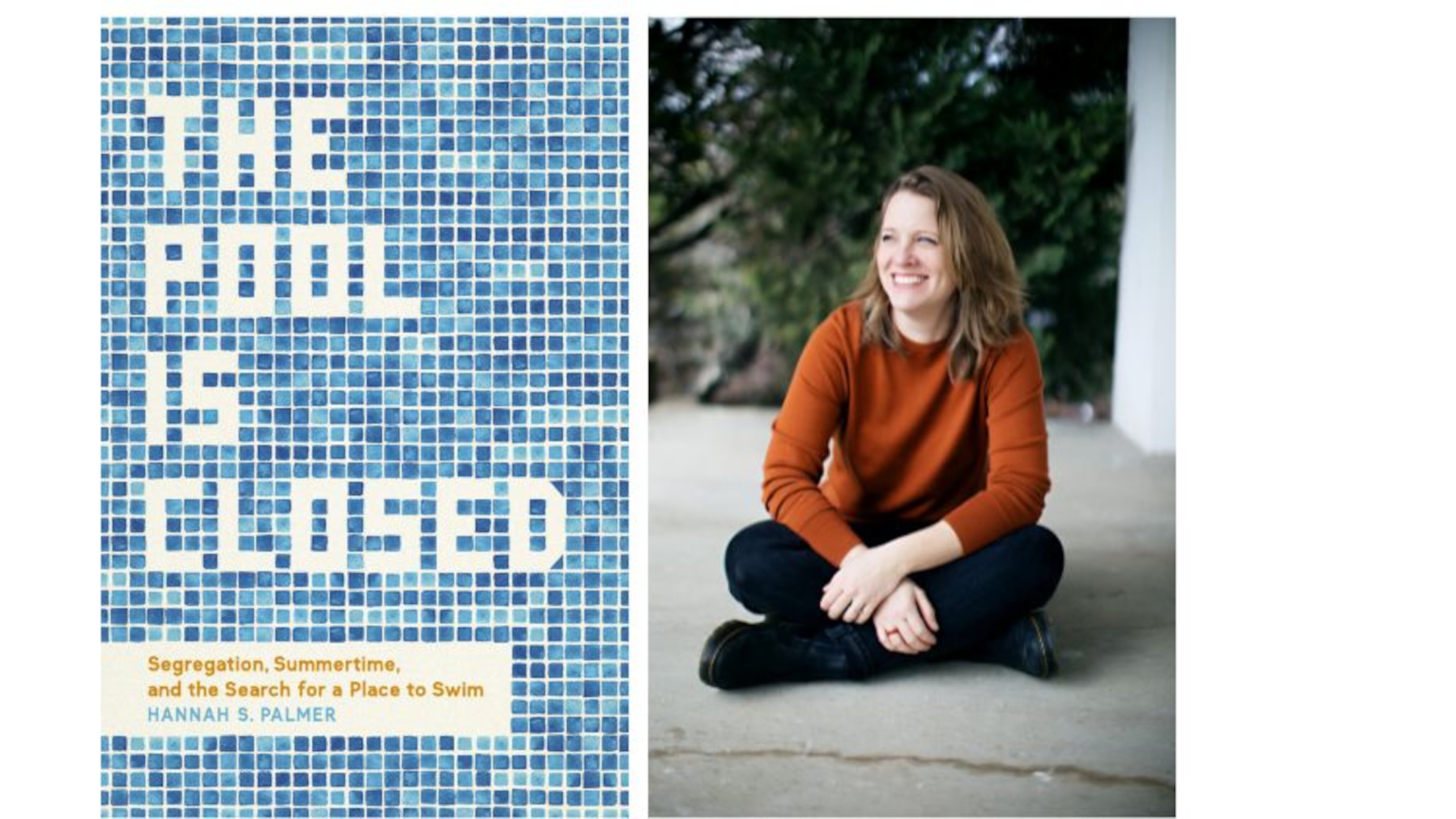

My best guess is that this took place around 1962, just before Jim Crow laws were overturned and public spaces were integrated. But as Hannah S. Palmer’s new book “The Pool Is Closed” (LSU Press, $34.95) illustrates, some things haven’t changed.

Blending elements of memoir, reportage, environmental activism and social commentary, Palmer examines the history and contemporary landscape of Atlanta’s public pools, recreational lakes and waterways. Along the way she discovers that access to them remains restricted along racial lines.

Challenged to teach her young sons how to swim in a community without a pool, Palmer spent a year taking her kids to public pools across Atlanta — there were 19 at the time — and her book is organized like a journal of their experiences and interactions along the way.

“I was trying to capture the hustle of being a mom … It was a lot of labor,” she said. “I wanted to really document that labor. I was like, this is a project. Let me document what a mess it is — the logistical mess, the emotional mess. And when it turned out to be a social and racial mess, too, I wanted to put all that in the book.”

Palmer’s quest overlapped with her interest as an urban naturalist committed to cleaning up the city’s waterways, specifically her work with the Finding the Flint river restoration project. So, the book also includes detours to polluted streams, drained lake beds and natural springs buried beneath parking lots to flesh out a bigger picture of environmental racism.

Palmer’s previous book was “Flight Path” (Hub City Press, $16.95), a 2017 memoir that traced the history of her childhood homes erased from the landscape by the expansion of the Atlanta airport.

For “The Pool Is Closed,” Palmer doesn’t have to look farther than her own neighborhood of East Point to find public pools that fell into disrepair and were closed after integration. But she focuses on Lake Spivey Park as an example of a community cutting off its nose to spite its face.

The lake was created in the mid-50s when developers dammed Rum Creek and flooded farmland in Clayton County. Sand was trucked in to create a beach and an amusement park was built. It was a popular attraction that closed suddenly. The reason owners gave was patrons’ “resistance to the integration of Lake Spivey in compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

Palmer questions whether it was the patrons who were resistant or the owners. The land has since been parceled up into lakefront lots for private residences, each with its own dock. There is no public access to Lake Spivey anymore.

Communities denying themselves amenities — like recreational facilities or public transportation — because they don’t want to attract “outsiders” is an old story. The tragedy is that it’s still happening today. Palmer points to Tybee Island as an example.

“The residents recognized even though you’re on the coast … it’s tough to learn how to swim at the beach,” Palmer said.

In 2012, residents built a grassroots campaign around a proposal to construct a public swimming pool on the island. They found a location, identified a funding source and got a referendum on the ballot, but it was defeated.

“The voiced concern about the pool is that it would be too expensive,” but in truth, “the campaign turned very racist,” said Palmer. “The undercurrent, the unspoken fear was that this pool would attract outsiders to the island that were not white and would bring foreign influence to the island.”

What happened at Tybee, Palmer said, “showed how much things have just not changed at all.”

To those who legitimately believe a pool is an unnecessary luxury that shouldn’t be publicly funded, Palmer said, “for people who don’t know how to swim, it’s not a luxury, it’s lifesaving. … For the kids who didn’t learn how to swim in East Point, generations now have not learned how to swim.”

Palmer will discuss “The Pool Is Closed” on Jan. 18 at Hapeville Depot Museum. For details go to hapevilledepot.org.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She may be reached at Suzanne.VanAtten@ajc.com.