The first characteristic we learn about teenage Missy Belue is that she is intensely inquisitive.

She obsesses over a single encyclopedia, the letter “s,” with special attention to the passage on sexuality — a storm cloud of foreshadowing. A so-called “old soul,” “Missy had eyes that were deep and brown and, like her daddy said more than once, eyes that suggested she had seen a great deal of what the world had to offer. But it was all a lie. Missy rarely stepped foot outside of Kingstree.”

This slender, tender coming-of-age story, Scott Gould’s debut novel, thrums with existential loneliness. All of its lost, threadbare souls, Missy especially, grasp for connection in the deep South during the 1970s. A mood of claustrophobia hangs over them as palpably as Spanish moss.

A devoted “daddy’s girl,” Missy reels from his unexpected death. Her distant, bleary-eyed mother copes with Smirnoff and immediately marries the unctuous mortician who has a bossy streak and a disturbing fetish. Missy finds herself living in the funeral home, a grim, formaldehyde-scented purgatory. Bristling with inchoate yearning, she simply wants to flee, with no particular destination in mind.

Anyone who has ever aimlessly cruised a downtown square will note that Gould is especially adept at rendering the miasmic ennui of this territory: “This Saturday, Missy and Angela planned to do the usual. Ride around town in the oversized, wood-paneled station wagon and appear aloof and bored to the people they passed.”

Missy’s long legs, swinging hair and precocity catch the eye of her roguish, significantly older third cousin, Skyles. With a ponytail that suggests nonconformity and a penchant for odd, thoughtful trivia, he at first seems like a possible passport to a broader world of ideas for Missy — a mentor or partner in crime. He keeps a flask at the ready and lives out of his pickup truck. Mischievous and philosophical, he is the kind of man who would describe himself, with a wink, as a “road scholar.” The sort of man who can incite a restless girl to make reckless decisions.

Missy, a woman-child, is at that awkward, vulnerable age of just starting to toy, tentatively, with her power. She proposes to Skyles that they run away together. “‘Why in the world should I take you on the road with me?’ He paused and waited for the answer. Missy thought for a moment, then crept to the verge of telling him everything. … All of the reasons why staying was more unbearable than running away. Instead, she just said, ‘Because you couldn’t stand to leave me behind,’ and the second she said it, she knew it was the kind of thing a woman would say to get a man to do whatever she wanted. She felt grown up, instantly.”

At this point, “Whereabouts” becomes a picaresque, and Missy finally, happily, sees some new scenery. She and Skyles drift from one scabby campground to another in the South, stopping at the occasional greasy spoon along the way. (Gould’s lengthy description of a fried baloney sandwich will churn your guts.) Missy fancies herself a romantic nomad. “She loved being the stranger in a strange place, a walking mystery, especially to people sitting in front of barbershops or on front porches.”

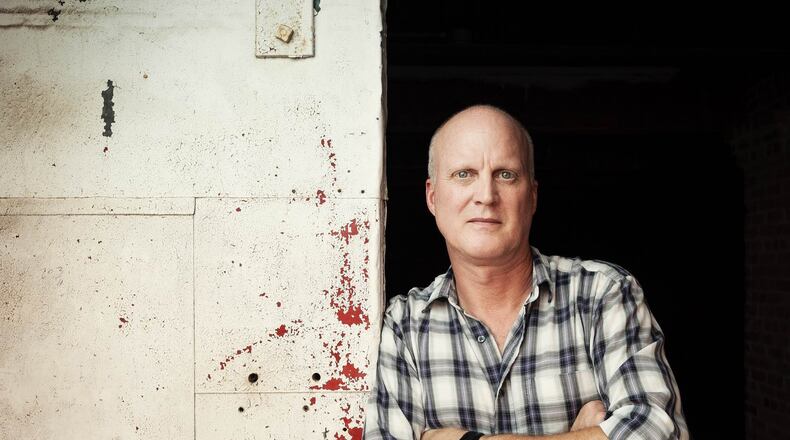

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

This unformed, still-growing heroine is not exactly smitten with Skyles, but she tries to please him, using her meager funds to buy him a book that she later finds in the campground trash-can. They have passionless, desultory sex, which is cast as an expected trade-off for the ride. “Like most people who lived in Kingstree, Missy knew there existed a kind of community incest tiny Southern towns practiced — intermarriage inside the city limits between the hometown boys and girls.” She just takes the practice to its logical, literal conclusion with an actual relative, no big deal.

Her time with Skyles feels protracted; impatience builds as the odometer racks up the miles. When will she wise up and leave this loser? Where will she go, if she does? It is the nature of these stagnant arrangements that they drag on a little too long. When she finally bolts, it comes as a relief, even as we fear for her safety, taking a ride with some AWOL Marines.

It is men who derail her, and men who save her; other women do not play much of a role in Missy’s life. She ends up in a faded uniform, waiting tables at the Lil’ Pancake House, off the interstate. Hassan, the owner, takes pity on her. He may well be the most sympathetic figure in the novel, with his funny verbal tics and shabby motel room plastered in travel posters that suggest his thwarted dreams of adventure. Missy, though, is a little too feral to reciprocate; she betrays his unfaltering kindness. She is not always easy to root for, but something about her scrappy survival instincts merits admiration. You have seen raw-boned women like her at truck-stops, wiping down Formica and growing old before their time.

Gould, who lives in Sans Souci, South Carolina, established himself as an award-winning writer of short stories that have drawn comparisons with Flannery O’Connor. His mastery of that form shows in this richly observed novel, the chapters of which could be broken down as discrete set pieces. They are distinctly Southern but gritty, without a whiff of moonlight and magnolias. The drawls are implied without being overstated.

Missy does, in the end, find what looks like redemption, or at least a fresh start.

FICTION

‘Whereabouts’

by Scott Gould

Köehler Books

243 pages, $18.95