Flannery O’Conner was famously dissatisfied with her first drafts. She rewrote, revised and reconsidered, struggling, she once said, like a squirrel on a treadmill.

She spent five years writing her first novel, “Wise Blood,” and seven writing her second, “The Violent Bear It Away.”

Considering her reluctance to publish the imperfect, how would she feel about the fragments of an unfinished third novel seeing the light of day?

“Those are ethical questions, and I don’t have a clear answer,” said O’Connor scholar Jessica Hooten Wilson, who has spent the last 14 years editing a version of that novel, “Why Do The Heathen Rage?”

“I don’t know, if there was a metaverse, if I would do it differently,” she added. “I loved so much of the material that I kept going forward with it. I hope I did the right thing.”

Wilson, chaired professor of literature at Pepperdine University in Malibu, California, decided that, incomplete or not, the fragments of the unfinished work should be introduced to the reading public.

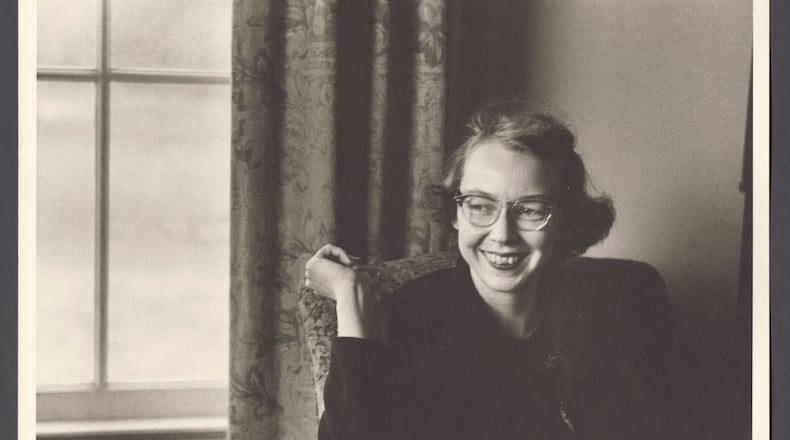

Credit: Andrea Barnett

Credit: Andrea Barnett

Labeled as a “behind-the-scenes look at a work in progress,” the book — “Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage?” (Brazos Press, $24.99) — will be released Jan. 23. O’Connor’s chapters are interspersed with Wilson’s explanatory segments, in which she describes the evolution of the ideas in the book and the influences and events in O’Connor’s life at the time.

O’Connor has been having something of a moment. In addition to Wilson’s book, “Wildcat,” a biopic on O’Connor’s early career co-written by Ethan Hawke and starring his daughter, Maya Hawke, premiered at the Telluride Film Festival in September.

Mary Flannery O’Connor, one of Georgia’s most noted writers, was born in Savannah in 1925, the only child of Edward and Regina O’Connor. Her father died of complications from lupus erythematosus in 1941. The daughter was diagnosed with the same illness 11 years later and would die of lupus in 1964, at the age of 39.

O’Connor assumed (rightfully, as it turned out) that her diagnosis was a death sentence, and she worked strenuously to beat that deadline, completing two novels and two collections of short stories. But her time ran out before “Heathen” was done.

Assembling the third novel is a challenge other scholars have declined.

“Everybody I’ve ever talked to about reading the ‘Heathen’ manuscripts said there’s no novel there,” said Bruce Gentry. “You’re just watching her (O’Connor) struggle.”

Gentry is a former professor at O’Connor’s alma mater, Georgia College & State University, and the former editor of the Flannery O’Connor Review.

O’Connor scholar Sarah Gordon also had her doubts. The last time she looked at the pages, which are kept in the GCSU archives, she determined that the material was “not at all promising,” she wrote in an email. (Gordon is professor emerita at GCSU and founding editor of the Flannery O’Connor Review.)

But Wilson, who earned her Ph.D. at Baylor University with a dissertation on O’Connor and Fyodor Dostoevsky, saw the potential in O’Connor’s unfinished work from the moment she encountered it.

Credit: Brazos Press

Credit: Brazos Press

In 2010, Wilson first saw the manuscripts: 20 files in folders numbered 215 to 234, a total of 378 hand-written and type-written pages of scattered scenes. Some scenes were rewritten many times, and the same characters seem to try on different names.

The chapters tell the story of Walter, a balding, pale intellectual who lives with his parents and has given up his dreams. His mother is a diminutive container of grim determination who despairs that her 28-year-old son is of no use on their farm or anywhere else. His father is recovering from a stroke and seems to prefer his Black attendant, Roosevelt, to Walter.

Walter writes letters to strangers to annoy them and amuse himself, and he has corresponded with a civil rights activist named Oona. Walter pretends that he’s a Black man in love with her, to test Oona’s open-mindedness.

Wilson wrote several articles on the material and in 2015 the estate of Flannery O’Connor invited her to prepare the unpublished fiction for publication. She spent two years transcribing everything that was there, then tried her hand at sewing the bits together with her own writing.

The scenes Wilson created include a first meeting of Oona and Walter, “some traipsing around the farm” and a visit to a commune loosely based on Koinonia, the Georgia interracial farm in Americus attacked by the Klan in 1957.

According to Wilson, her editors said “nice try, but this isn’t Flannery. This is you.” Wilson concedes: “lt was fan fiction.”

So, instead of gluing the scenes together with her own fiction, Wilson opted to insert annotations. The book also includes seven black and white linoleum-cut illustrations by Steve Prince of One Fish Studio.

Wilson’s analytical asides, separated by brackets, look at the real-life friends and acquaintances that served as models for some of O’Connor’s characters, such as her friend Maryat Lee, who may have inspired the socially conscious Oona.

In “Heathen” O’Connor appears to be using Oona as an object of fun, a Northern liberal on a self-appointed mission to help those in the benighted South. But the tone isn’t clear. Walter also appears to be falling in love.

Is O’Connor’s intent to make fun of integrationists? Wilson examines O’Connor’s attitude about race, which has been questioned in recent years. O’Connor’s fiction lampoons whites who presume they are superior to African Americans, but her private correspondence casually used offensive epithets and expressed doubts about the civil rights movement leaders.

Paul Elie’s 2020 New Yorker essay, “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” brought the issue to the forefront, and in August of that year O’Connor’s name was taken off a dormitory at Loyola University Maryland.

O’Connor scholars point out that the deeply Catholic writer was concerned more with grace than with race, and that her stories detail those often-violent moments when a redemptive spirit breaks into a fallen world.

Wilson said O’Connor struggled with race in her fiction, partly because she had few Black friends and was poorly equipped to write a convincing Black character. She said “Heathen” demonstrates that O’Connor was moving in a new direction.

“So many people said Flannery never dealt with race, that she hid from the controversy and stepped back from activism,” said Wilson. “They don’t know she was still on her way.”

Like Dostoevsky, who was an antisemite but a genius, O’Connor may have been a flawed human being, but her art gives us a vision of something that is universal, said Wilson.

“We need to recognize that they are human beings and where their art reaches beyond their humanness.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured