Paris has its Mona Lisa and Italy its David.

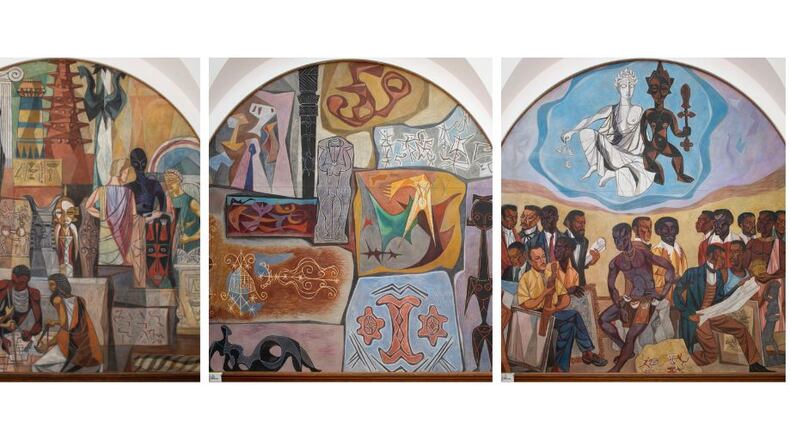

But in the pantheon of American art, Atlanta has its own under-the-radar masterwork: Hale Aspacio Woodruff’s epic six-part mural “The Art of the Negro” which has hung for six decades in the Trevor Arnett Library rotunda outside the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum.

If those paintings and sculptures in the Louvre and the Accademia Gallery of Florence attest to Europe’s art world supremacy, then Woodruff’s mural is a vision of a new world of African and African American creativity that challenged those Eurocentric norms.

The mural is also central to Atlanta’s identity as a center for racial progress played out in music, art and politics.

Academics and curators regularly travel from around the world to see Woodruff’s mural. And scholars like Christian Kravagna, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, laud its innovative approach. Writing in London’s Tate museum website, Kravagna said, “‘The Art of the Negro’ was of vital importance in offering an alternative history of global art from the Black perspective.”

Historically resonant, the six 12-by-12-foot panels created between 1950 and 1951 are also thrillingly beautiful, executed in the muted pastels so indicative of their ‘50s origin. But those subdued colors coexist with Woodruff’s bold critique. In “The Art of the Negro” Woodruff addresses eternal issues of art looting, indigenous art traditions, Colonialism and the often denigrated creative output of non-Western artists.

“Their significance was enormous for the time,” said Danille Taylor, director of the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum (CAUAM), who often leads groups of students and visitors on tours of the murals.

“These works were conceived in the 1940s,” said Taylor, “when there was no other place in the Deep South where African Americans could go to graduate school. And he put these murals here to inspire them.”

Born in Illinois and raised in Nashville, Woodruff studied at the Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis and at the Art Institute of Chicago. After graduation he spent four definitive years in Paris beginning in 1927.

But Atlanta was a formative stop in Woodruff’s life.

Credit: Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

Credit: Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

Upon his arrival in Atlanta in 1931, Woodruff took a streetcar to the Atlanta Art Association (now the High Museum) and asked to speak to the museum’s director. A Black janitor who watched him walk through the museum’s front door told him he was the first Black man to have ever done so. During his 15 years at Atlanta University, Woodruff established the university’s art program and the Atlanta University Art Annuals (1942–70) to counter the lack of exhibition opportunities for many African American artists.

During a break from teaching in 1938 Woodruff honed his skills working side by side with one of the mural form’s icons — Mexican artist Diego Rivera. Woodruff assisted Rivera in creating murals for the Hotel Reforma in Mexico City. CAUMA curator Clarke Brown says she sees evidence of Rivera’s influence in the geometric forms that define Woodruff’s work in “The Art of the Negro.”

Following his time with Rivera, Woodruff was commissioned to create the Amistad murals at Alabama’s Talladega College, which, in part, depict the slave rebellion aboard the Spanish slave ship La Amistad. In 2012 those newly restored murals traveled the country in an exhibition organized by the High Museum of Art.

Woodruff’s third surviving mural “The Negro in California History — Settlement and Development,” (1949) was commissioned by the Black-owned Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company in Los Angeles.

“The Art of the Negro” was Woodruff’s final mural, unveiled in 1952. It was inspired by Woodruff’s far ranging interests — in the art of Africa, regionalism and classical oil painting. Though Woodruff’s Amistad murals are marked by the crisp, representational social realism of Diego Rivera, “The Art of the Negro” murals are indebted to abstraction and cubism, offering a far more stylized vision of the Black experience.

“The Art of the Negro” is a midcentury “Black Panther” and reclamation of Black heroism and influence, offering a corrective to the long-held idea that artists like Picasso, Matisse and Cezanne invented modernism.

“I’ve always had a high regard and respect for the African artist and his art. So this mural … is for me a kind of token of my esteem for African art,” Woodruff told Al Murray of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in a 1968 interview.

The panels chart a history of the role of Africans and African Americans in art making. Part one: “Native Forms,” shows the foundation of art in African ritual, sculpture, performance and dance.

Credit: Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

Credit: Clark Atlanta University Art Museum

“This is traditional Africa and shows you how art is created and used within context,” said Taylor. At the apex of the painting is a representation of the African god of thunder, Shango, who CAUMA eventually adopted as the museum’s official logo.

The second painting “Interchange,” moves ahead in time to the ancient world and features Greek, Roman and Egyptian figures working together to create music, mathematics, linguistics and art. But Woodruff places African figures “a little higher to represent that they are bringing knowledge to the table,” said Taylor.

Panel three, “Dissipation” is a melee of Colonialist violence and depicts the sacking of Benin in 1897 when British soldiers looted treasures from that West African country. Those artworks eventually found their way into British museums and private collections. Soldiers hoist sculptures of African figures over their heads in fits of destruction. Abstracted ribbons of fire rise from the scene.

In “Parallels” Woodruff moves beyond African influence to show the artistic contributions of a wide swath of cultures, including Mayan, Aztec and Native American. During his time in Paris, said Taylor, Woodruff was exposed to African and other indigenous artworks that imprinted themselves on his visual language.

In the fifth panel, “Influences” Woodruff evokes an art gallery exhibition of paintings and sculptures assembled one on top of the other, all of them showing the influence of African forms in modernism.

The final work in the series, “Muses,” said Taylor, “is a pantheon of real artists across time,” including Woodruff holding an African sculpture, Henry O. Tanner, Jacob Lawrence and Charles Alston. At the crest of the painting sit two female muses, one African and one European, to attest to what Taylor calls Woodruff’s double consciousness.

CAUMA regularly loans its collection of some 1,100 works to institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of New York, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and the Brooklyn Museum. The Woodruff murals, however, have never moved beyond the walls of Clark Atlanta, even during a $75,000 conservation financed by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Layers of grime and smoke from hundreds of cigarettes huffed at university gatherings and mixers from the ‘50s until today were removed during that 2022 restoration. “They’re so much brighter,” said Taylor.

Most recently, the Art Institute of Chicago has included life-size replicas of the murals at the entrance to the critically celebrated exhibition “Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica.” Critic Alison Cuddy writing for Chicago’s NewCity calls the inclusion of the high-resolution reproduction of Woodruff’s murals “a touchstone for the entire exhibition.”

Even today, contemporary curators and historians recognize the ongoing resonance of Woodruff’s mural.

“I think for 1952 this was an extraordinarily radical work,” said Taylor.

ART EXHIBIT

“The Art of the Negro.” 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday-Friday. Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, Trevor Arnett Hall, Second Floor, 223 James P. Brawley Drive SW, Atlanta. 404-880-6102, www.cau.edu/art-museum

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured