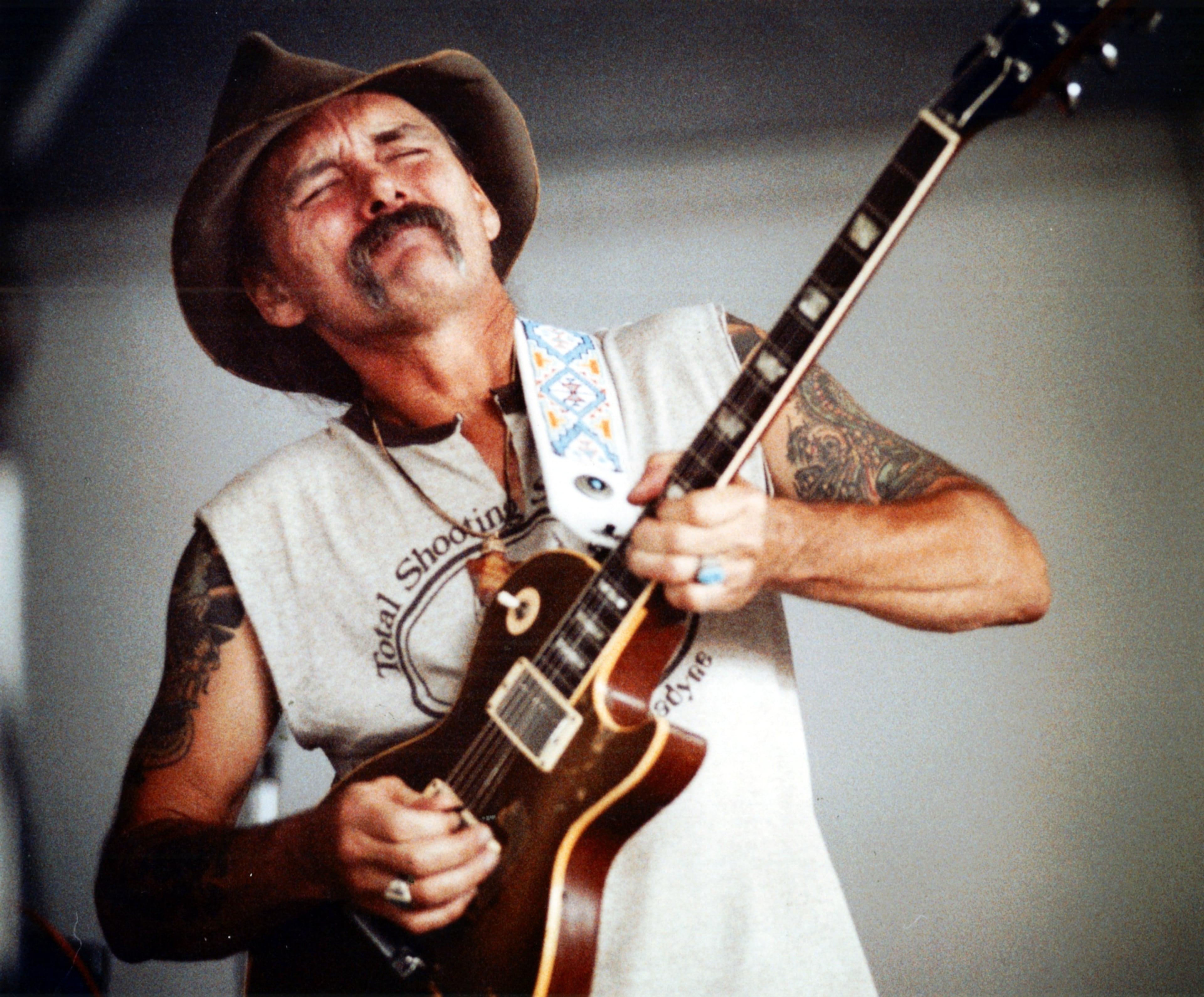

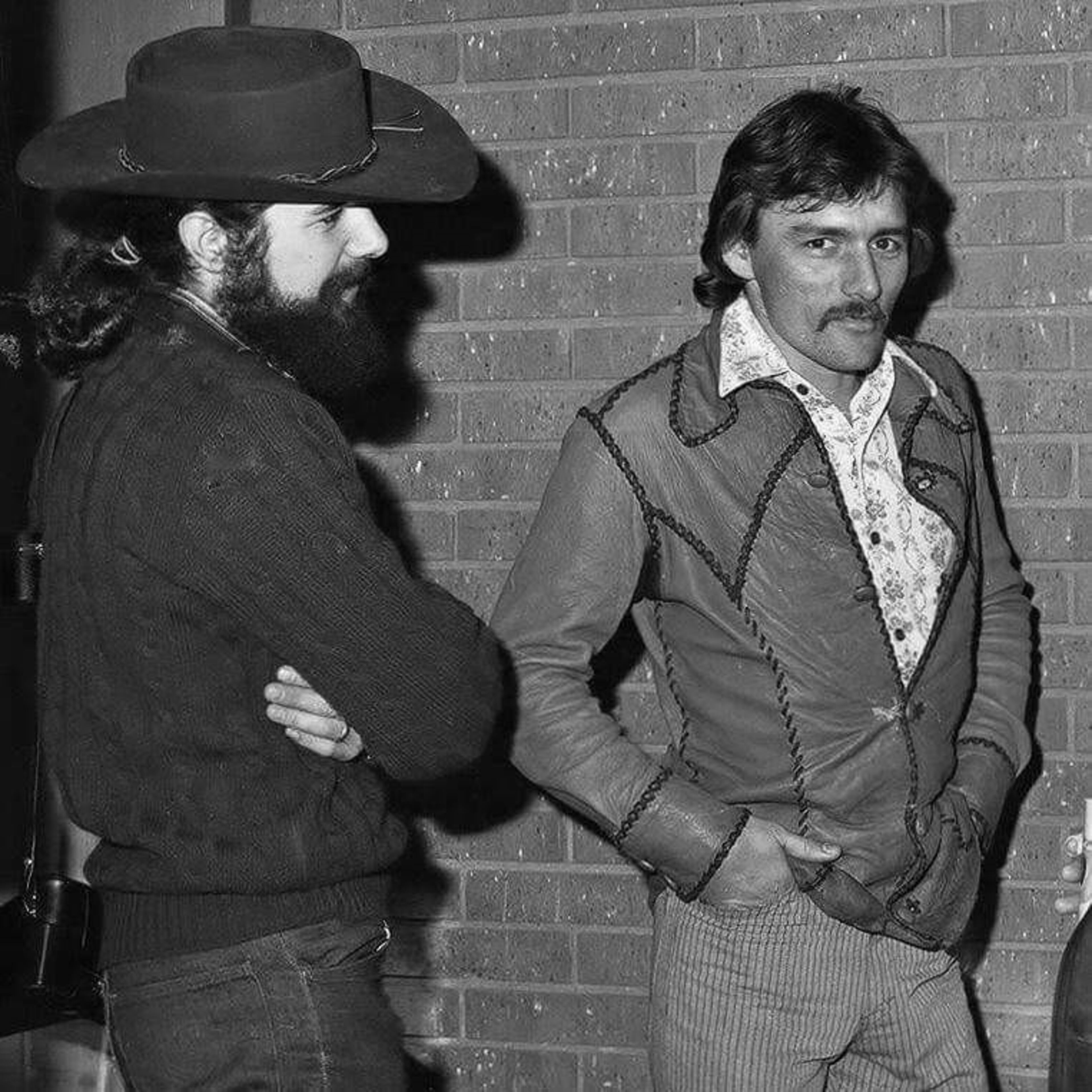

Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts dies at 80

Dickey Betts was responsible for some of the Allman Brothers Band’s most enduring and beloved songs: “Blue Sky,” “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” “Jessica” and the band’s lone Top 10 hit, “Ramblin’ Man.”

The Rock & Roll Hall of Famer died at his home in Osprey, Florida, David Spero, Betts’ manager of 20 years, confirmed to the AP. Betts had been battling cancer for more than a year and had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Spero said.

With Betts’ death at age 80, drummer Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson is the sole remaining original member of the band that brought Southern rock to the masses.

Forrest Richard Betts was born Dec. 12, 1943, and was raised in the Bradenton, Florida, area, near the highway 41 he sang about in “Ramblin’ Man.” His family had lived in the area since the mid-19th century.

The Allman Brothers Band formed in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1969, but moved to Macon soon after the classic lineup of brothers Gregg and Duane Allman, Betts, bassist Berry Oakley and drummers Johanson and Butch Trucks was set. They were drawn there because Phil Walden, formerly Otis Redding’s manager, was launching a new label, Capricorn, and the Allmans were going to be its flagship act.

Macon would become the band’s home, and they recorded parts of their second album, 1970’s “Idlewild South,” at the city’s Capricorn Sound Studios. That same year, they established the Big House, a 1904-built Tudor residence on Vineville Avenue as the band’s commune, which it would remain until 1973. The house is now the Allman Brothers Band Museum. A table from H&H soul food restaurant, where Betts wrote “Ramblin’ Man” at 4 a.m. in the early 1970s, sits in the kitchen.

The band’s first two albums didn’t exactly set the charts alight, but they began to build a following as a stellar live ensemble through hard touring, playing some fondly remembered local shows such as Piedmont Park appearances in 1969 and 1970 and gig at the second Atlanta International Pop Festival in 1970. The band’s live reputation would lead to the breakthrough double live album “At Fillmore East,” recorded in the famed New York City venue.

“Fillmore” climbed to No. 13 on the album chart and was certified gold within a few months of its July 1971 release. It’s a showcase for the group’s sublime onstage chemistry, especially the heavenly harmonies of Betts’ and Duane Allman’s intertwining guitars. Rolling Stone, in a 2002 review, called it “the finest live rock performance ever committed to vinyl.”

Then came the tragic deaths of Duane Allman in October 1971 and Oakley a little more than a year later — from motorcycle accidents three blocks apart in Macon.

The band had already started recording the fourth album, “Eat a Peach,” before Duane Allman’s death. It would top the chart performance of its predecessor, landing at No. 4 on the Billboard album chart, and contained another Betts classic, “Blue Sky.”

“Brothers and Sisters,” released in 1973, would find Betts at the forefront of the band, contributing four of the album’s seven songs, including “Ramblin’ Man,” still a staple of classic rock radio. The LP would spend five weeks at No. 1.

But things began to fall apart after that. The reception for the follow-up album, 1975′s “Win, Lose of Draw,” was less than enthusiastic. The Allman Brothers were still a big draw on the tour that followed, and it was around this time that the band would play a benefit for then-presidential candidate Jimmy Carter. Following the news of the guitarist’s death, the Carter Center sent took note on X (formerly Twitter), saying, “We send our condolences to the family of Dickey Betts, co-founder of the Allman Brothers Band. President Carter loved their music, and the band campaigned on his behalf.”

Gregg Allman would later remember that benefit as a rare highlight of the time, as noted in Alan Paul’s “One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band,” but the first breakup would come soon after.

A reunion in the late ‘70s-early ‘80s followed, then a brief run for the group Betts, Hall, Leavell and Trucks, where Betts joined forces with Wet Willie’s Jimmy Hall, and fellow Allman Brothers alumni Trucks and keyboardist Chuck Leavell. The Allman Brothers Band would reunite for the band’s 20th anniversary in 1989. Members would come and go in the years that followed, and there was often tension and infighting, but a final break with Betts came in 2000. His last show with the band was at Atlanta’s Music Midtown on May 7, 2000.

He would continue performing and recording with both Great Southern and the Dickey Betts Band, until a stroke in 2018 forced the cancellation of his remaining tour dates.

Leavell, an Allman Brothers member during the height of their stardom in the early and middle 1970s, said of Betts’ death, “It’s certainly a sad day to lose such a good friend and such a great musician.”

The two musicians kept in touch over the years.

“I checked on him every now and then. He was enjoying life, I think,” Leavell said. “But with the health challenge, that slowed things down for him.”

A longtime touring performer with the Rolling Stones who makes his home near Macon, Leavell told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution by phone from Los Angeles that Betts “leaves an amazing and enviable legacy.”

“I’m as proud as I can be that I had the privilege of working with him throughout my career,” he said.

Leavell spoke of the genius of Betts’ “Ramblin’ Man” and “Jessica,” which showcased Leavell’s prowess on keyboards.

“I have to give a special thanks to Dickey for writing a song [”Jessica”] that lent itself to be so welcoming for a piano part,” Leavell said. “I was honored to be the person that played that part.”

The Associated Press and Joe Kovac Jr. contributed to this story