Decatur author Robert Weintraub recounts a funny story in his biography of tennis pioneer Alice Marble about her visit to Atlanta for the 1939 world premiere of “Gone with the Wind,” which she attended with Carole Lombard and Clark Gable, the film’s costar.

The trio shared adjoining rooms at the Georgian Terrace, and one day the women had a good laugh when Gable took a bath with his blinds open, inviting the prying eyes of fans with binoculars who watched him from buildings across the street.

Weintraub writes: “‘Don’t you want to go in there and draw the blinds?' Alice gasped. ‘What, and spoil their fun?’ Lombard replied.”

It is an amusing story, but it is also probably untrue.

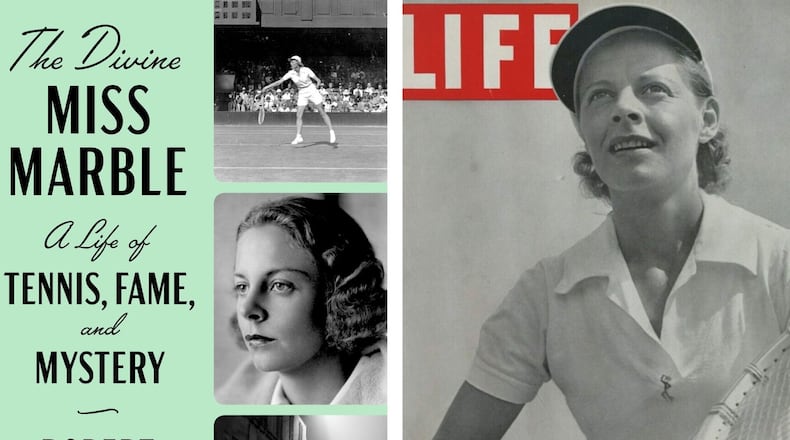

Such is the conundrum of Alice Marble and the challenge Weintraub encountered researching and writing “The Divine Miss Marble: A Life of Tennis, Fame and Mystery” (Penguin Random House, $28), published this week.

Marble was a pioneer in more ways than one. She overcame tremendous odds, including poverty and tuberculosis, to win the U.S. national championship in 1936 at age 23. Three years later, she won Wimbledon. A forerunner of the multi-hyphenate celebrity, she increased her fame exponentially by becoming a singer, a writer, a fashion designer and a darling of the Hollywood social set.

She was also a champion of racial diversity in tennis, a bisexual and, to hear her tell it, a Nazi spy for U.S. Intelligence, which got her shot in the back for her efforts.

Weintraub’s interest in Marble was piqued by her tremendous athleticism, combined with her independent spirit and modern sensibilities. But the more he learned about her, the more fascinated he became.

“She was like an onion,” he said. “Every time you peeled a layer of skin away, there was something more to discover underneath.”

Weintraub, 52, is a TV producer and author of books about the Yankees and Babe Ruth. When he hasn’t been busy helping his parents relocate to Georgia from two coronavirus hot spots, Florida and Los Angeles, he has spent the pandemic sheltering at home and going through withdrawal from a summer without baseball.

“The good thing about being a writer is you’re a socially distanced, shut-in person anyway, so there’s not a huge difference,” he said in a phone conversation last week.

According to Weintraub, Marble was an extremely willful person.

“She was undeterred, not just by the hurdles she had to overcome, like disease and various other ailments, but the sexism of the age and the amateurism that prevented her from making the money she deserved,” he said. “She was also very unafraid to make her opinions and feelings known, especially when it came to fighting prejudice, both misogyny and racial. But she was also very guarded and secretive in her personal life.”

In Weintraub’s telling, Marble was practically predestined to join forces early on with Eleanor Tennant, the Los Angeles-based tennis coach to the stars, who became a controlling influence over every aspect of Marble’s life.

“This woman who was her coach/Svengali was cut from the same cloth,” said Weintraub. “They were both very independent and did not confine themselves to the social mores of the time. (Marble) fed off Eleanor’s behaviors and maybe took it to another level.”

Marble wrote two autobiographies before she died at age 77 in 1990. The first one was fairly straightforward, but the second one, “Courting Danger,” published the year after her death, made many claims that took her friends by surprise. Among them were tales of a marriage to a military hero killed in action during World War II and her role as a spy.

Weintraub’s exhaustive attempts to verify her claims proved futile, prompting him to conclude they were most likely fabrications.

He attributes Marble’s tall tales partly to her having a bit of fun with her public persona, but also to her resentment over not getting the riches and lasting glory she thought she deserved for her career, which was cut short by the war.

Credit: LIZ STUBBS

Credit: LIZ STUBBS

“It still surprises me that she would embellish her life as much as she did because there was so much that was true and worthy of celebration,” he said.

Marble’s “Gone with the Wind” story is one of the tales from her second book that raised a red flag for Weintraub.

“I give her the benefit of the doubt that there was a 10 percent chance she was there,” he said with a chuckle. More likely, though, he believes it’s a case of good old-fashioned storytelling.

“Even when she was playing tennis, she was very much about putting on a show and giving the audience their money’s worth,” said Weintraub. “Not just putting butts in seats, but giving them something to talk about on their way home.”

Weintraub accomplishes the same thing with “The Divine Miss Marble.” It’s good solid storytelling that gives the reader plenty to chew on. The only difference is, his account is true.

Suzanne Van Atten is an award-winning book critic and contributing editor for the AJC. svanatten@ajc.com

About the Author

The Latest

Featured