Travis Hunter, one of college football’s most valuable players, has impressed at every level

Colorado defensive coordinator Robert Livingston spent more than a decade in the NFL ranks, where he was surrounded by top football talent.

Livingston said Heisman Trophy favorite Travis Hunter is a rare talent with game preparation like Adam “Pacman” Jones and a work ethic comparable to former Georgia and NFL star A.J. Green, who was “the hardest worker [he’d] ever been around.”

“There was never a snap count with Travis. What he does is amazing — he’s playing both ways at elevation, 5,430 feet. It’s the real deal,” said Livingston, noting that Hunter averaged about 120 snaps per game.

“Travis could do anything,” Livingston said.

Heisman Trophy 2024

Travis Hunter wins Heisman Trophy

At his high school, they have stories and memories of Heisman winner Travis Hunter

Hunter, one of college football’s most valuable players, has impressed at every level

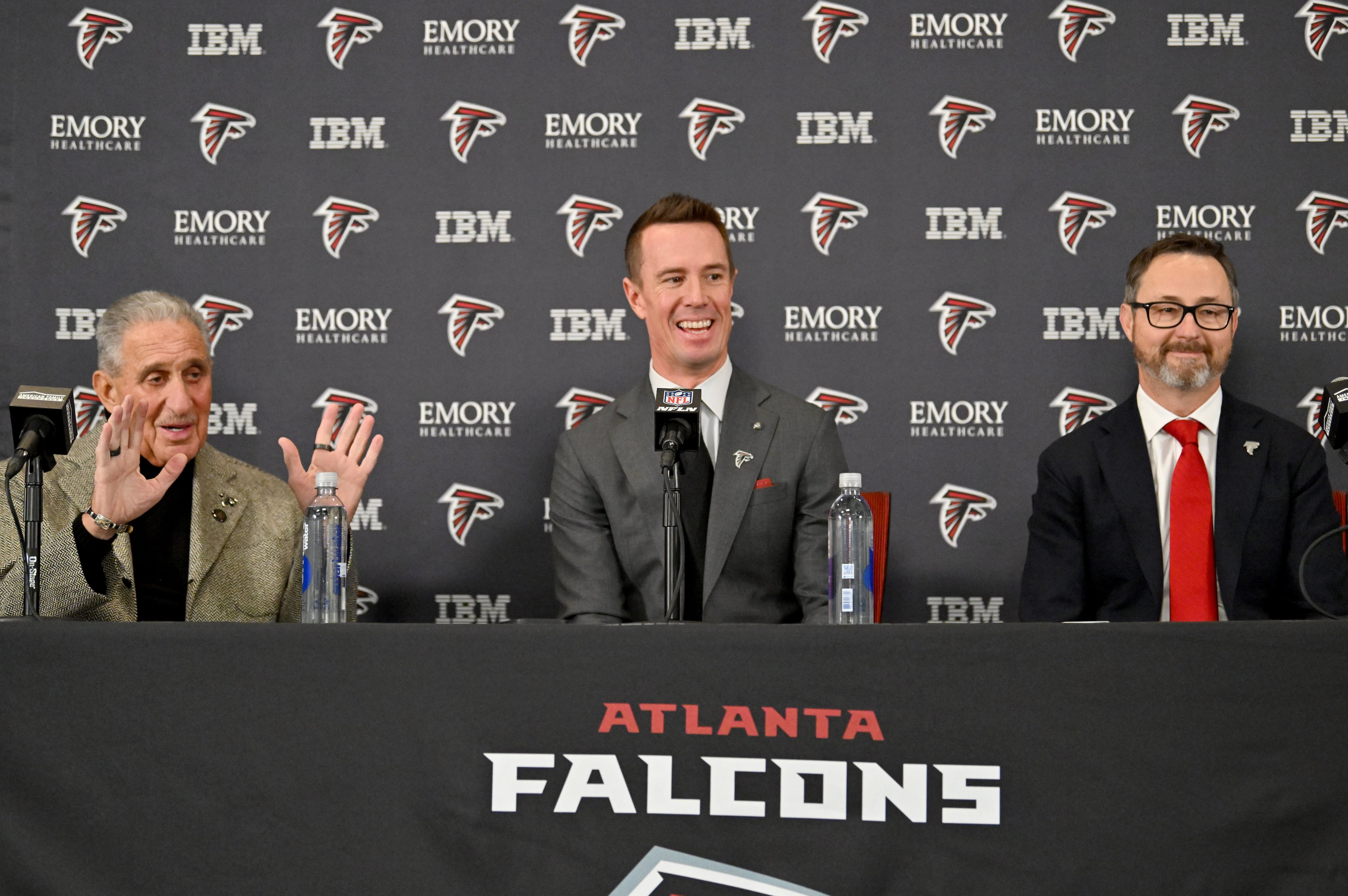

Photos from the 2024 Heisman ceremony and related

Heisman finalist Travis Hunter ‘grateful’ to have started journey at Collins Hill

Hunter was high school player of the year and an AJC Super 11 pick

Other Heisman Trophy winners from Georgia

Profiles of the Heisman finalists

Heisman Trophy is named for John Heisman, who coached 15 years at Georgia Tech

Livingston recalled when the Buffaloes were playing North Dakota State and the game was in a TV timeout, and the defense was looking at certain adjustments.

“Travis taps me and says, ‘Coach, I’ll be right back,’” Livingston said. “All the sudden I hear the crowd roar, and I look up at the video board, and he’s running 65 yards for a touchdown. That was his ‘I’ll be right back’ moment.”

Hunter, who figures to become about $40 million richer on April 24 in Green Bay, Wisconsin, the site of the 2025 NFL draft, is the latest one-of-a-kind football star of his generation.

Gordon Central coach Lenny Gregory, who coached Hunter at Collins Hill — along with about 150 other FBS scholarship players during his stints at Grayson and Centennial — knew what he had in Hunter on July 24, 2018.

That was the day Hunter, a rising freshman with no previous introduction or workout regimen, breezed through a series of six 200-yard sprints without breaking a sweat.

Gregory watched in awe as Hunter’s football legacy began.

“He’s a great kid, has a big heart and is always nice to people,” Gregory said. “And then he’s an unbelievable player that does stuff that’s almost superhuman, things other people can’t do.

“Everything he’s touched has turned to gold.”

While Hunter’s football feats are impressive, his business savvy, in the era of NIL, has proved just as impressive.

Travis Hunter’s awards, accolades and NIL value

Hunter’s NIL valuation is north of $5 million, according to On3, making him one of the most valuable collegiate athletes today. He’s made dozens of deals during his three-year college career, at Jackson Statein 2022 and at Colorado the past two years.

Most recently, global athletic accessory and footwear giant Adidas signed Hunter to an endorsement deal, with a limited edition apparel collection released Thursday.

Social analytics company General Sentiment estimated that Baylor University earned the equivalent of $14 million in media mentions after Robert Griffin III won the Heisman Trophy in 2011, with the school estimating that the award added $250 million in donations, sponsors, ticket deals and TV contract expansion, according to ESPN.

Hunter already has become the first player in history to win both the Biletnikoff Award (best receiver) and Bednarik Award (best defensive player) in the same season.

This, along with the AP college football player of the year, Big 12 defensive player of the year, Lott IMPACT Trophy winner, Paul Hornung Award winner and Walter Camp Award winner, cements Hunter’s first-ballot College Football Hall of Fame status and his future appearance — and autograph — value.

It’s an accepted concept that sports are a business, and that’s never been more true in the college football world than now, with players free to negotiate NIL deals and unrestricted free agency in the form of the transfer portal.

Hunter, as much as he’s benefited from his ability to run, jump, catch, cut, defend and tackle, might have hit a sweet spot, with pending legislation that could put more guardrails in place around schools’ ability to throw seven-figure deals at student-athletes.

Hunter undoubtedly has benefited from the modern era of college football, but people involved in his growth and development in metro Atlanta cite his cornerstones as his passion for the game and love of preparation.

There were reports that Hunter, the nation’s No. 1-rated recruit in his class, chose Jackson State because of of a seven-figure NIL deal.

However, Colorado coach Deion Sanders told the Jackson (Miss.) Clarion Ledger that those reports were ‘the biggest lie I’ve ever heard.’ The On3 valuations report does not include any mention of a deal with Barstool Sports.

Hunter, who originally committed to play at Florida State, has maintained that his development takes priority over money.

Sanders, popularly known as Coach Prime, starred at Florida State before launching a two-sport career that saw him play for NFL teams in Atlanta, San Francisco, Dallas, Washington and Baltimore and Major League Baseball teams in New York, Atlanta, San Francisco and Cincinnati.

Ahead of trying to recruit Hunter, Sanders underwent surgery in December 2022 to remove two toes on his left foot because of blood clots, preventing him from traveling to see Hunter in person for his recruiting pitch.

But a virtual meeting did the trick. Little did Hunter know at the time how close he would grow to Sanders.

“He’s more than just a coach — he’s a father,” Hunter said during a Pivot podcast. “I texted him one game, ‘Coach you changed my life forever.’ Just being able to see where I’m at now, I don’t know where I’d be at now if I went to Florida State.”

Sanders once famously arrived on a game day for the Florida State-Florida rivalry in a limo, his self-styled marketing ahead of its time. Hunter picked the appropriate mentor, in every respect, though he recently revealed that his first NIL-related purchase was not a car, but rather a boat.

“That’s my peace,” said Hunter, who professes to bait a hook as effectively as he lures quarterbacks into ill-advised passes in his direction

When Sanders was hired away from Jackson State to recharge a once-proud national championship program at Colorado, Hunter had no desire to go fishing for a better deal.

“If I wanted to transfer somewhere else, I could have got a major amount of money, but it ain’t about the money, it’s about getting to the NFL,” Hunter said earlier this season on his video podcast, “The Travis Hunter Show.”

“The NFL is going to set you for life; the NIL can only set you for a moment,” Hunter said. “You see where I’m at with the best coach that’s going to put me in the best situation.”

The discovery of young Travis Hunter

Hunter found his football beginning in Suwanee after his family moved him, along with his younger brother, Trayvis, from West Palm Beach,Florida, to Georgia in his eighth grade year.

Hunter wandered into Georgia Sports Performance and was playing pickup basketball when Collins Hill Youth Athletic Association football director Ray Hicks noticed the soon-to-be ninth grader dunking.

“I was like, ‘Man, this kid is good, a hooper,’” Hicks said. “But then I look over on the turf field at GSP, and there was his little brother, 10 years old, running routes like a grown man.”

Hicks approached the younger Hunter and asked how he could get ahold of his parents, wanting him to sign up for the Collins Hill youth football program. When 10-year-old Trayvis said he was with his older brother, Hicks turned his attention to the elder Hunter.

Hicks then got Hunter’s parents in contact with Gregory to get him registered at Collins Hill.

It was straight to varsity for Hunter, who, despite his smallish frame, was able to cover Marietta’s 245-pound, 5-star prospect Arik Gilbert, a junior then.

Earl Williams, owner, operator, trainer and 7-on-7 coach at GSP, saw Hunter the day Hicks approached him at the gym and later against Gilbert.

“Travis was serious about his football,” Williams said. “I came up with a job to put some money in his pocket. He’d come over and get his workout in and help young kids learning to play receiver, always making sure his little brother came here with him.”

Travis Hunter revealed in his podcast that having Trayvis — a class of 2027 prospect at Effingham County — helped the transition into a new city and state.

“It was kind of easy for me because I had my little brother with me; he was my right-hand man,” Hunter said on The Pivot podcast.

“The first thing I told my trainer was, ‘I want to be the best player you ever trained or coached ... and to this day I’m trying to have that mindset,” Hunter said.

Williams said Hunter wasn’t big on weights when he first began cutting his teeth at GSP, but he quickly grew into it.

Williams has trained dozens of NFL, college and high school players over the years, including Alabama’s Justice Haynes, Clemson’s Phil Moffett, Missouri’s Sam Horn and Los Angeles Chargers quarterback Taylor Heinicke.

“A trainer is not going to make Travis Hunter. What a trainer does is inspire a young man and give him the guard rails and expectations,” Williams said. “Greatness is about the chase, the journey; perfection is never reached, and Travis has that mindset.”

Hunter quickly became known on the 7-on-7 fields. Williams said he’ll never forget when Hunter sped across the field to break up a pass against one of Cam Newton’s prolific summer squads. Hunter’s flair and ability impressed Newton, according to Williams.

Hunter, with Williams’ blessing, played on the national 7-on-7 circuit in Newton’s championship program the next year.

Four years later, not much has changed, with Hunter still dominating receivers and defensive backs.

Rob Patton, now in his fifth year as Social Circle head coach after coaching Hunter his freshman year, can’t get the early memories of Hunter out of his mind.

“One of the first days he was there, the kids are standing around; he did several backflips in a row,” Patton said. “Yeah, he was special, and a great kid, a really quiet kid, not loud or obnoxious, always quiet in film study, always asking intelligent questions about the team we were playing.”

Patton often picked up Hunter for school his freshman year, pulling up to his home at 6:30 a.m. Hunter would watch Hudl tapes, typically of upcoming opponents.

Up next for Hunter

Hunter would be the first Colorado player to win the Heisman Trophy since Rashaan Salaam in 1994, and the first two-way player in college football since Charles Woodson (1997).

Hunter is among the finalists, which include Boise State running back Ashton Jeanty, Oregon quarterback Dillon Gabriel and Miami quarterback Cam Ward, all of whom will be at the ceremony in New York City.

Hunter could join a fraternity of Georgia high school greats that includes Herschel Walker (Johnson County, 1982), George Rogers (Duluth, 1980), Charlie Ward (Thomas County Central, 1993) and Cam Newton (Westlake, 2010).

“It’s going to mean so much to me; I know I’m going to break down and cry after everybody goes away,” Hunter said. “I’m going to try to act tough in front of everybody, but for my family, it’s going to mean so much: I’m the first to go to college, first to get to the NFL, and I’ll be able to take care of my family the rest of my life.”

More Stories

The Latest