The father was a nervous wreck.

The son was not.

Tripp Morris was running on little sleep as he sat alert in the rest area of the International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) World Cup competition center alongside a team of weightlifting coaches and sports psychologists earlier this month. His 20-year-old son, Hampton Morris, already completed his weigh-in and was busy loading up on calories. Tripp was too anxious to eat.

Hampton needed to rank in the top 10 in his weight class by the end of the competition to qualify for the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris and this was the final round. Hampton entered the event ranked seventh, but whether he qualified depended on others’ performances. He needed to do well, yes, but he also needed his opponents to do poorly.

As Tripp kept track of results from other competitors’ lifts, he did some quick mental math. A realization dawned on him. Hampton stepped out to use the restroom.

Once his son was out of sight, Tripp turned to his colleagues from USA Weightlifting.

“Hamp just made the Olympics,” he said.

With this knowledge in his possession and his son preparing to attempt a record-setting lift, one question remained: do they tell Hampton about qualifying before his final lift, or wait to keep him focused on the task ahead? To Tripp, the answer was obvious.

The start of the journey

Residents of Marietta, Tripp and Hampton’s journey to the IWF World Cup in Phuket, Thailand was the culmination of a decade of hard work. Their personalities could not be more different, but weightlifting was something that the father and son could share. With Tripp coaching and Hampton training, their personality styles fit. They also shared another crucial similarity: high expectations.

It all started in area CrossFit gyms, where Hampton says he grew up watching his parents work out. This exposure to barbells piqued an early interest. When Tripp coached 9-year-old Hampton’s recreational soccer team, he suggested his son try working with the barbell to gain strength for soccer. As it turned out, Hampton was much better at weightlifting than he was at soccer. More importantly, he loved it.

“Hamp is not naturally athletic,” said Tripp, recalling his son’s early days in the gym. “Every bit of athleticism, Hamp has worked very hard to earn.”

Starting with basic movements like squats and deadlifts, Morris progressed to a more advanced training program in his preteen years. He participated in his first local weightlifting competition at age 12, and a year later, he competed in his first national competition. The 2017 Nike Youth National Championships in Atlanta were just a short drive from the Morris family’s home in Marietta. There, he hit a 58-kilogram snatch and an 80-kilogram clean and jerk, sweeping gold and setting three new American records.

“It was at that point that I decided I wanted to stop playing soccer,” said Hampton, reflecting on his success in 2017. “Stopped really doing anything else and just focused on weightlifting.”

What started as a fun way to gain strength evolved into something much different. He realized that with discipline and focus, he had the unique potential to take weightlifting to the next level.

Mike Gattone, a coach with USA Weightlifting, first met Morris at a youth Pan-Am competition around this time.

“He was the youngest kid on the team, and he had this purplish-blue streak in his hair, kind of swept down over one eye,” Gattone said. “The kid won medals on the first or second day of competition. And I remember thinking it was so cute, because he walked around with his medals on the rest of the time there.”

In need of a coach

But every elite athlete needs an elite coach. Tripp never envisioned himself taking on that role; the world of competitive weightlifting was foreign to him, and coaching Hampton in the early days stressed him out.

“The first time we ever did it, I was teaching him how to clean, and I wasn’t 30 seconds into doing it before I was getting so stressed,” Tripp said. “He was rounding his back and I was afraid it was going to hurt him.”

As the self-described “type-A” member of the Morris family, Tripp said he didn’t want to be everything to Hampton: he was already dad, disciplinarian and planner. He worried adding coach to that list might overwhelm his son. But when the search for a professional coach went nowhere (or at least, nowhere affordable), Tripp decided to step up.

Twenty international competitions later, the pair seem to have hit their stride.

“He taught himself the sport and you know, his philosophies and his ideas brought this kid to this level,” Gattone said of Tripp. “It’s just crazy.”

In the years since Hampton first competed, some things have changed. Now, he can lift three times his body weight above his head.

But other things haven’t. Namely, his personal discipline and commitment to his rituals.

Credit: Stars Platform 1DX

Credit: Stars Platform 1DX

An avid reader, he told documentarian Nate Cerwinske that he has a schedule for which books he reads and when – self-improvement tips between sets, classics before bedtime. These parts of his identity fit perfectly into his training routine, which explains why they’ve stuck. Nothing can interfere with his regimen. Weightlifting comes first, always.

Hampton doesn’t even have his driver’s license yet because he isn’t willing to sacrifice training time. Since graduating from Pope High School in 2022, Morris has spent every waking moment either in training or in recovery. His parents even moved to a house with a three-car garage so they could convert it into a home gym.

“I don’t get out,” Hampton said. “Weightlifting is the only thing that I do.”

Sunday through Wednesday are his working days, where he typically spends six hours in the gym. Thursday is a full recovery day, when he says he attends physical therapy and massage therapy. Friday is an easier primer day, when he preps for his heavy day on Saturday maxing out the snatch and clean and jerk. For Hampton, training is a full-time job.

Gattone says Hampton’s consistency and strict discipline are what truly set him apart from other weightlifters he’s worked with. Most teenagers tend to give themselves cheat days or prioritize their social lives, but Morris never did.

“He’s so perfectly fit for the rigors of the sport,” Gattone said. “It can be very solitary. It’s not a team sport. So, it’s hard to get kids through, especially the very sensitive teen years, you know, and then come out the other side and still be a weightlifter.”

Despite Hampton’s many successes, the road hasn’t always been easy. For Tripp, Hampton’s snatch is a significant issue area. The snatch is a very technical and violent Olympic lift. It typically requires time to develop a solid technique — the older the weightlifter, the better their snatch becomes. As Tripp explains it, the clean and jerk (Hampton’s specialty) comes more easily. But considering how long he’s been lifting, Tripp worries that Hampton is falling behind.

In part, he blames himself. “He struggles in snatch quite a bit,” Tripp said. “And I worry that his lag in snatch isn’t just associated with his age. I take it personally, I can’t help it.”

But at the end of the day, Tripp said, understanding the inner workings of his son’s mind is what he struggles with most.

“If you were to ask me to compare my confidence level in teaching snatch and my confidence level in understanding him, I’d say my understanding in coaching the snatch is probably higher,” Tripp said.

Hampton is stoic and thoughtful. His father says he has an overdeveloped sense of fairness, and Gattone describes him as a gentle soul. Sometimes, Tripp says it can take his son time to think things through before he responds if he responds at all.

Tripp isn’t that. A chemist by trade, he approaches life with precision, meticulously planning every detail. He’s hyper self-aware and relies heavily on emotional intelligence to navigate the world. He’s also the one in charge of all travel prep, logistics and programming. He doesn’t sleep enough.

Sometimes, he says, they test each other’s patience. But they really love each other too.

“It’s a bit of an ebb and flow,” Tripp said, reflecting on his relationship with his son. “Right now, thankfully, it’s really great timing. We’re getting along really well, in and out of the gym.”

Hampton agrees, adding that the pair have come a long way since he first started weightlifting.

“He’s really learned to understand what I need in the moment,” Hampton said, “especially in those very stressful situations.”

To tell or not to tell

Stressful situations just like the one Tripp found himself managing only a few weeks ago at the IWF World Cup.

To tell Hampton about his newfound Olympian status or not? Most people in the room quickly reacted. No, no, no. It was a bad idea. It would distract him.

Tripp had no doubt that they were wrong. He knows his son.

“I honestly was just being respectful asking the question,” Tripp said, laughing. “I was going to tell him regardless.”

When Tripp broke the news, he says Hampton’s smile touched his ears and stayed like that for the remaining hour and half before his big lift.

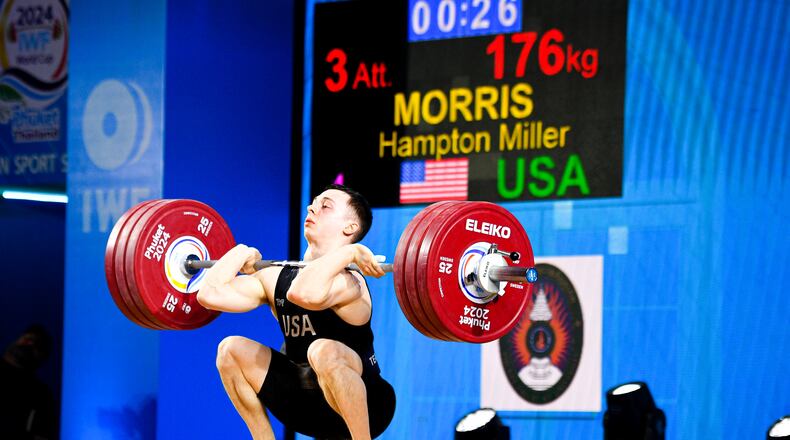

Relaxed, Hampton went on to execute a historic 176 kilogram clean and jerk, breaking the senior world record in the 61-kilogram weight class and moving up to second in the Olympic qualifying rankings. He is the first American to break a senior world record in weightlifting since 1969.

In Paris, Morris will have the chance to make history once again: the United States hasn’t medaled in men’s weightlifting since 1984. This time, the world will be watching.

“It’s just something that connected for him in this particular sport and activity,” Gattone said. “And whenever that happens, you’ve just got to kind of get out of the way, be in awe and watch it go.”

Julianna Russ is a student in the sports media certificate program at the Carmical Sports Media Institute at the University of Georgia.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured