Malcolm Brogdon left a part of his heart in Africa.

In trips to the continent as a child, he saw poverty he never knew existed. He returns now to help the people who had such a profound impact on the direction of his life.

Brogdon, an Atlanta native and current NBA player for the Indiana Pacers, took family trips to Ghana and Malawi as education and service experiences at ages 10 and 13. A year ago, the 28-year-old established the Brogdon Family Foundation, which includes the Hoops4Humanity initiative. Its focus is providing clean water, enhanced educational opportunities and sustainable approaches to improve health for children and families in Africa.

“Both of those trips really lit the fire for me,” Brogdon told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution after returning from a recent trip to Tanzania and Kenya. “I’m carrying on that flame now.”

Brogdon, who graduated from Greater Atlanta Christian and the University of Virginia, originally partnered with the Chris Long Foundation for several years. In working with his fellow Virginia alum, Brogdon had his own initiative called Hoops2o. It was there where he helped build 11 water wells in Africa. With the tools he learned, Brogdon branched out on his own in July 2020 with his own foundation keyed on equity and sustainability. His mother, Jann Adams, is the executive director of the foundation.

While he knows there is need worldwide, including in the United States, Brogdon said his calling is to make a difference in Africa. A calling that began to echo all those years ago.

“There are people everywhere who need help,” Brogdon said. “And some other places the suffering is worse. There are deeper levels of suffering on other continents and third-world countries. I think Africa gets a bad reputation, that you go there and it’s uncivilized or everybody is in poverty. It’s not like that at all. There are a lot of beautiful components of Africa. There are so many people doing well. But there is a good amount of poverty, and there are people struggling. That is where my heart is. It’s where my heart has been since I was a little kid.”

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

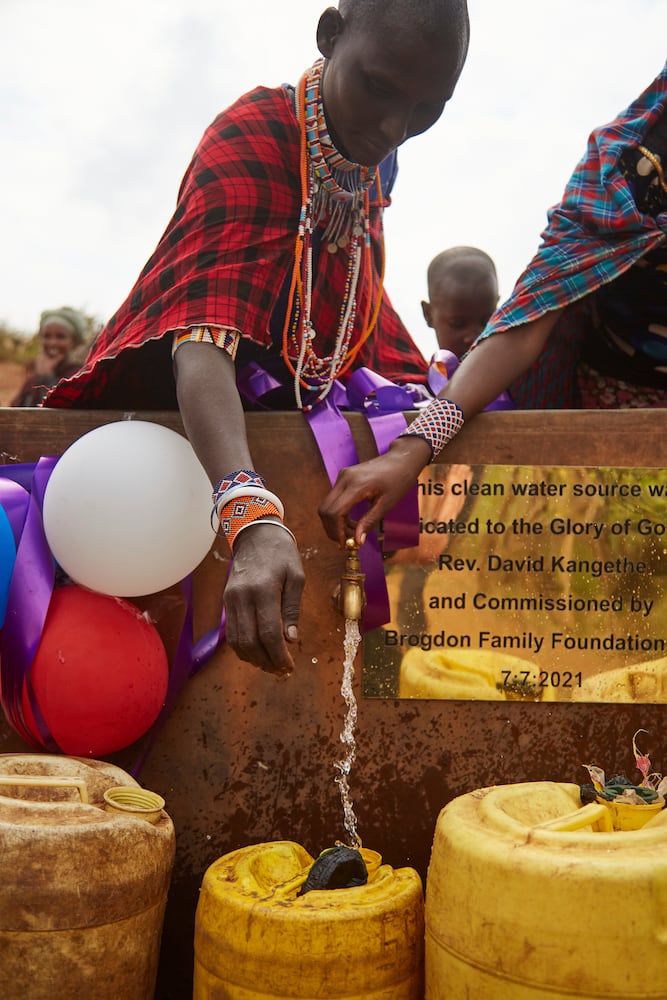

Sustainability is a major component of the foundation’s work. According to Adams, an estimated 790 million people in the world are without access to clean water. She also said that a reported 40% of the wells built in Africa are no longer operational. Part of their program for solar-powered wells is to empower people to maintain the well and create fair ways to distribute water.

In a holistic approach, the foundation work also focuses on hygiene and education, often partnering with nearby schools.

Wash stations are extremely important to the work. If a well is hundreds of yards away from a school, children don’t have a chance to wash their hands after using the restroom.

A part of empowering the community is the impact of the availability of clean water on women and girls, Adams said. In most cases, they are the ones responsible for fetching clean water, often devoting hours of the day to the basic human need.

“You realize the water source is often filthy, and animals are drinking from and bathing in it,” Adams said. “Water sources are also inaccessible. We are worried about that. If girls are spending their time getting water, they can’t go to school. We think that is the first step. The second step is to support the academic environment so everybody can advance. … That is really one of the things we are thinking about, how to impact girls and women even more. That’s really where we need to go.”

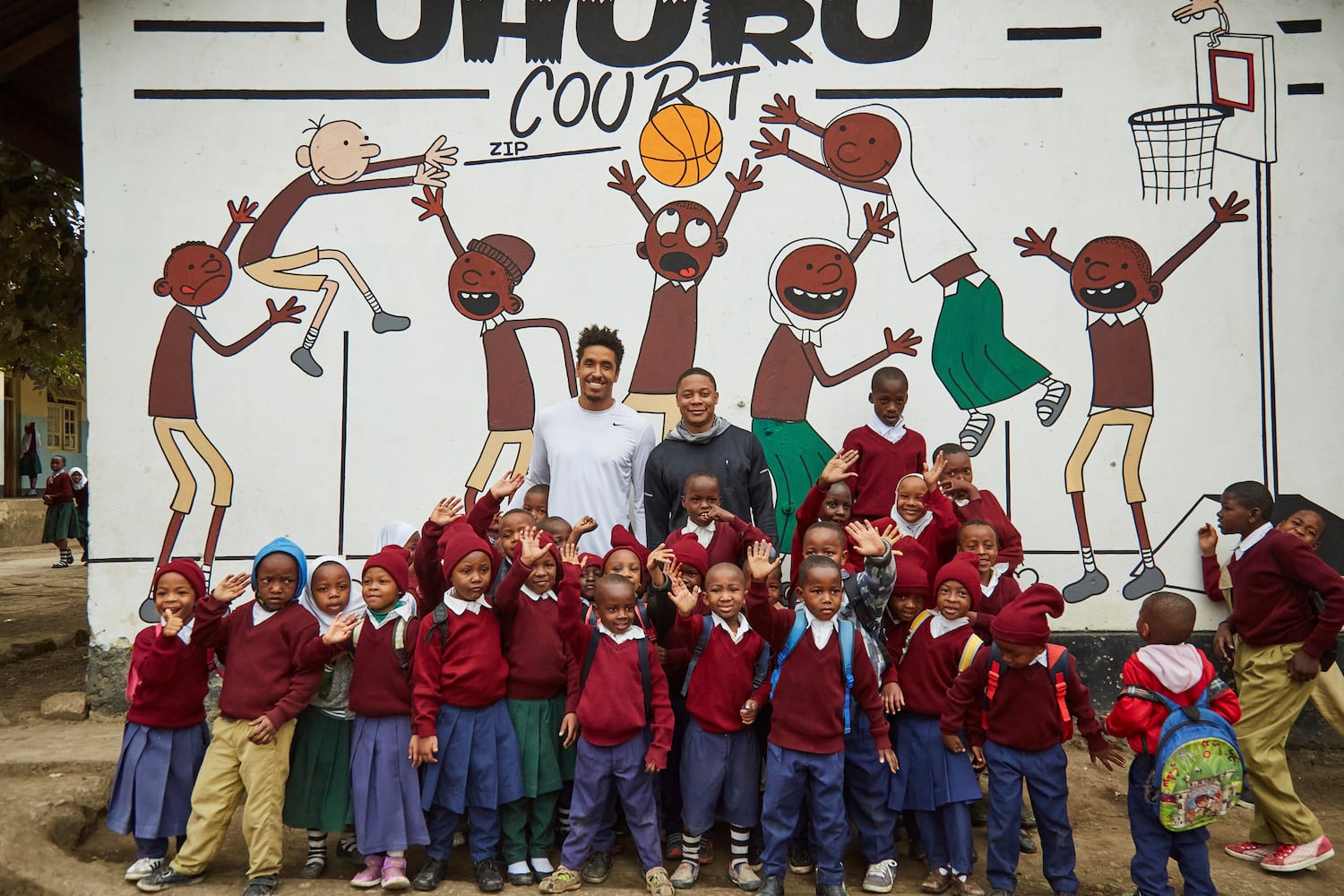

The second component of the foundation’s work in Africa is education. In partnering with local schools, it is able to provide needed supplies, including working with partner onebillon for tablets called onetab that supplement math and reading work. There are also plans for community gardens and basketball courts to help with a well-rounded and healthy experience. The foundation describes the impacted schools as “empowered schools.” By partnering with the school and community, the people are empowered to sustain the water source and the educational enhancements.

“My mom has taken me all over the world,” Brogdon said. “I’ve gone all over the world with basketball. I’ve seen a lot and just that exposure has helped me see and learn that people need help and sometimes going in there and giving people food if they are starving, giving food is not the answer. It’s not sustainable. I’ve watched that. You see that today. You have a lot of non-profits that go into Africa, Asia and all these places with struggling people and they give them food. That’s not sustainable. In a lot of cases, it’s doing worse for them.

“That’s not the route I wanted to take. I wanted to take a route that was different, that was really, really thoughtful and careful about how I approach people because there are their lives and sincerely wanted to help them.”

Brogdon uses his contacts to help his efforts. NBA player Tim Frazier made the most recent trip to Africa, which includes visits to previously built wells, locations for future work and time at a national park to see the beauty of the country and enjoy game drives, which Brogdon calls the gateway to getting others to help, others with a heart for the work. They visited the foundation’s first completed project at the Patanumbe School in Tanzania. The water well serves 7,000 community members, including 500 children attending the school.

Credit: Photo courtesy of the Brogdon Family Foundation/Clay Cook

Credit: Photo courtesy of the Brogdon Family Foundation/Clay Cook

“You get them there and they fall in love with the continent,” Brogdon said. “They fall in love with the work and how it impacts people.”

Hawks players Kevin Huerter and De’Andre Hunter have been involved in fundraising efforts.

The progress can be slow, Brogdon said. It takes patience to establish a foundation, find good partners worldwide and find the right situation. There are places where there is just no water, no matter how deep you drill. The successes can be incremental. However, each success is a success. It can be transformative – for everyone.

Adams has worked at Morehouse since 1990. She has moved into the administration and currently is an associate vice president and leads the Andrew Young Center for Global Leadership at the school. Yes, education is important to the Brogdons. His great-grandfather, grandparents and mother all are educators.

With the importance put on education by the Brogdon family, they also started the JHA Education Project, an initiative that helps closer to home. Named for his maternal grandfather, John H. Adams, the initiative supports schools in Indianapolis (and soon Atlanta) to support educational achievement with a focus on literacy, STEM and mentoring to create empowered schools in the U.S. In addition to an annual book-club experience and the provision of books and supplies, the foundation again turns to the holistic approach. Last year, they conducted virtual tours for high school juniors and seniors to HBCU’s Morehouse College, Howard University, Kentucky State University and Tennessee State University. The hope is for in-person visits next spring with a social-justice tour, including a visit to Atlanta’s Center for Civil and Human Rights.

There is more to come. There are more fundraisers, more contacts to make, more partnerships to secure. More help to give.

“It’s incredibly transformative in every aspect of life that you can really think about,” Brogdon said. “From education, to the nutrition. You can look at people and tell what a difference clean water is making with their skin, health and overall mood. They can taste it. Everyone can tell when they are drinking contaminated water. No one deserves to drink contaminated water. To me, the biggest thing I see is the joy on people’s faces.”

The work of the heart.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured