On the 25th anniversary of the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution presents a series of retrospectives produced by the University of Georgia’s Carmical Sports Media Institute. The Eyewitness to History interviews offer the view of someone who was at a top moment on the Summer Games.

Michael Johnson was the favorite to win the 200 meters at the 1992 Olympics but got food poisoning and did not qualify for the finals. The shortcoming set the stage for Johnson’s culminating moment in Atlanta.

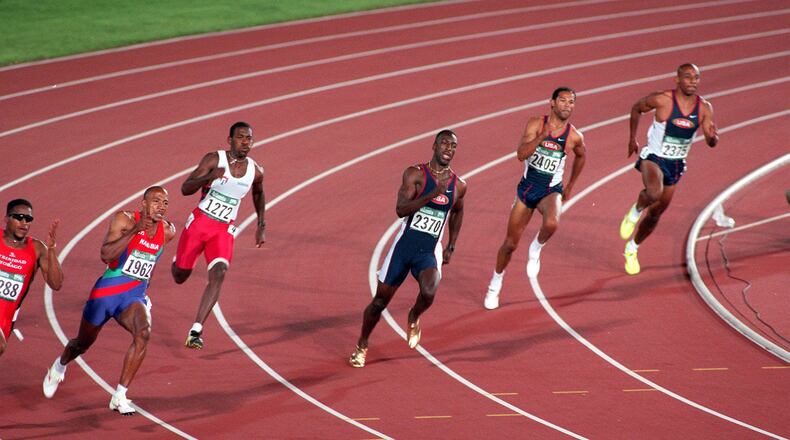

At the 1996 Summer Games, in his now famous gold spikes, Johnson set a world record in the 200 and became the first male athlete to win both the 200 and 400 in the same Olympics. He had set the Olympic record while winning the 400 and also won gold in the 4x400-meter relay before racing in the 200.

Highly regarded as one of U.S. track and field’s preeminent and most consistent sprinters of all time, Johnson made a name for himself early on, especially in his days at Baylor University.

At Baylor, Johnson developed a close relationship with then Bears head track and field coach Clyde Hart. That relationship carried into Johnson’s preparation for his shining Olympic moment in ’96.

“The semifinals and the finals of the 200 were on the same day with a two-hour break between them. After the semifinals of the 200, they told the eight finalists they had to go to a room underneath the stadium. And there was a small little area maybe 60-70 meters long that they could do some striding or just sit and kind of look at each other for two hours.

“Before the (final) race, I said, ‘Michael, as soon as this thing is over, and y’all walk out that tunnel, when they turn left to go back in there, you just keep walking straight because I’m going to be there — it was going to be a van parked right there on the street — and you’re going to get in the van, we’re going to go back to the warm-up track.’ ... And we go over and they’ve got the lights turned off. We could see by the streetlights. Then we do what I call a mini warm-up instead of doing a full hour and a half warm-up, we did 45 minutes. Instead of running four 100s, we ran two. I wanted it to be on his mind that it was just another race instead of sitting in there and staring at those other athletes, and worrying and using your adrenaline.

“When Michael came in (for the 200-meter final), the crowd was just going ‘Michael! Michael!’ and the (cameras) were all just flashing. The pressure was unbelievable. He goes over and he adjusts the starting blocks. When he gets them adjusted, he gets down, and kind of takes one practice start and comes back. And, he said, all of a sudden, for the first time, it dawned on him that ‘What if I don’t win — all this hype, all this stuff — and I don’t win, they’re gonna forget I won a gold medal in the 400 and set an Olympic record. I can get the silver medal or the bronze. It’s gonna be worth nothing. People are gonna be like I’m a failure.’ He said that’s the first moment he had any doubts. He said, ‘But before I could contemplate it, the starter said to set fire to the gun.’

“Michael got Lane 3, which certainly is more difficult to run because it’s a tighter curve. If you’d have your pick, you’d want to be out there in Lane 5 or 6. Well, he gets Lane 3. When the gun fires — to look at the rerun of that race — he catches the guy in Lane 4 before you can blink your eyes. It’s amazing. ... But he also looked like he stumbled just a little bit, just enough that he kind of took a deep breath.

“He had that doubt, that fear of failure, and had that rush of adrenaline. That’s what propelled him out of the blocks so fast, (then he) almost stumbled and caught that guy outside of him. And of course, his first hundred was run almost as fast as the winning time in the open hundred meters, him running around that curve was unbelievable. He ran it right at 10 seconds flat running around the curve, which is just — you’re not supposed to be able to do that.

“For the first time in my coaching career, I didn’t care if anybody knew who I was, patting me on the back. It was the first time I really felt solely self-gratification. Because we knew that we had done something we set out to do. ... We thought in ’88 we could do it. We thought in ’92 we could do it, and (we) sit down there and plan for four years. ‘This is what we got to do.’ You know, you can stub your toe. You can get food poisoning, as we did. A lot of things (can) happen. When you’ve got to run eight races, you can’t imagine the number of things that can happen to you. And to get through it all, it was just a relief that it was over. And we had done it.”

Sydney Gibbs and Evan Lasseter completed this interview as students at the University of Georgia’s Carmical Sports Media Institute.

Eyewitness to History: Richardson homer give U.S. softball gold

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured