Freddie Freeman, MVP: Excellence rewarded

Freddie Freeman arrived in the major leagues Sept. 1, 2010. He started that night, going 0-for-3 against the Mets. He wouldn’t start again until Sept. 26. The Braves entered the month leading Philadelphia by three games – down from seven July 22 – and were trying to win the National League East in Bobby Cox’s final season. Frank Wren had landed Derrek Lee at the trade deadline to play first base. It wasn’t the time to run out a rookie to see what he could do.

By Sept. 21, Philly had caught and passed the Braves. Its victory the night before at Citizens Bank Park behind Cole Hamels gave the Phillies a four-game lead with 11 to play. The second game of the series was going no better. The Braves trailed 5-2 against Roy Halladay, who’d worked a perfect game earlier in the year and who would spin a no-hitter in Round 1 of the playoffs.

The Braves had two out and nobody aboard in the seventh. Freeman pinch-hit for Peter Moylan. At that moment, Freeman was 1-for-13 with four strikeouts. His batting average and slugging percentage were the same -- .077. When he stepped in, we in the press box were busy chronicling another installment of a September swoon. We were only half-watching when Halladay delivered his first pitch.

The sound of bat on ball made us look. Freeman’s drive – a screaming liner of the sort with which we’d become familiar – landed in the stands in right-center. A guy who’d just turned 21 launched, as the first extra-base hit of his career, a massive home run off a pitcher who would soon win his second Cy Young. Nobody hit much against Halladay that year. Freeman went 1-for-1.

In those ancient days, Freeman was known mostly for being Jason Heyward’s minor-league roommate. Heyward’s first big-league home had been much more memorable – a three-run blast off Carlos Zambrano on opening day 2010 – and his rookie season gave us highlights by the bushel. He finished second to Buster Posey in rookie-of-the-year balloting. Back then, Heyward was the hottest property in baseball.

In February 2011, Sports Illustrated put Heyward and Freeman on its cover. It was clear, though, who was deemed the Alpha. Heyward is seated on a rolling basket of baseballs, his bat on his left shoulder. Freeman’s left hand is on Heyward’s right shoulder. Freeman’s bat is touching the ground. Part of Freeman’s body is obscured by Heyward’s.

Freeman would finish second in the 2011 ROY voting; teammate Craig Kimbrel was the unanimous winner. The most memorable Freeman moment of that season came at its end: He grounded into a double play in the 13th inning of the 162nd game, handing St. Louis the wild-card game and completing an epic September collapse. (Kimbrel blew a save that night.)

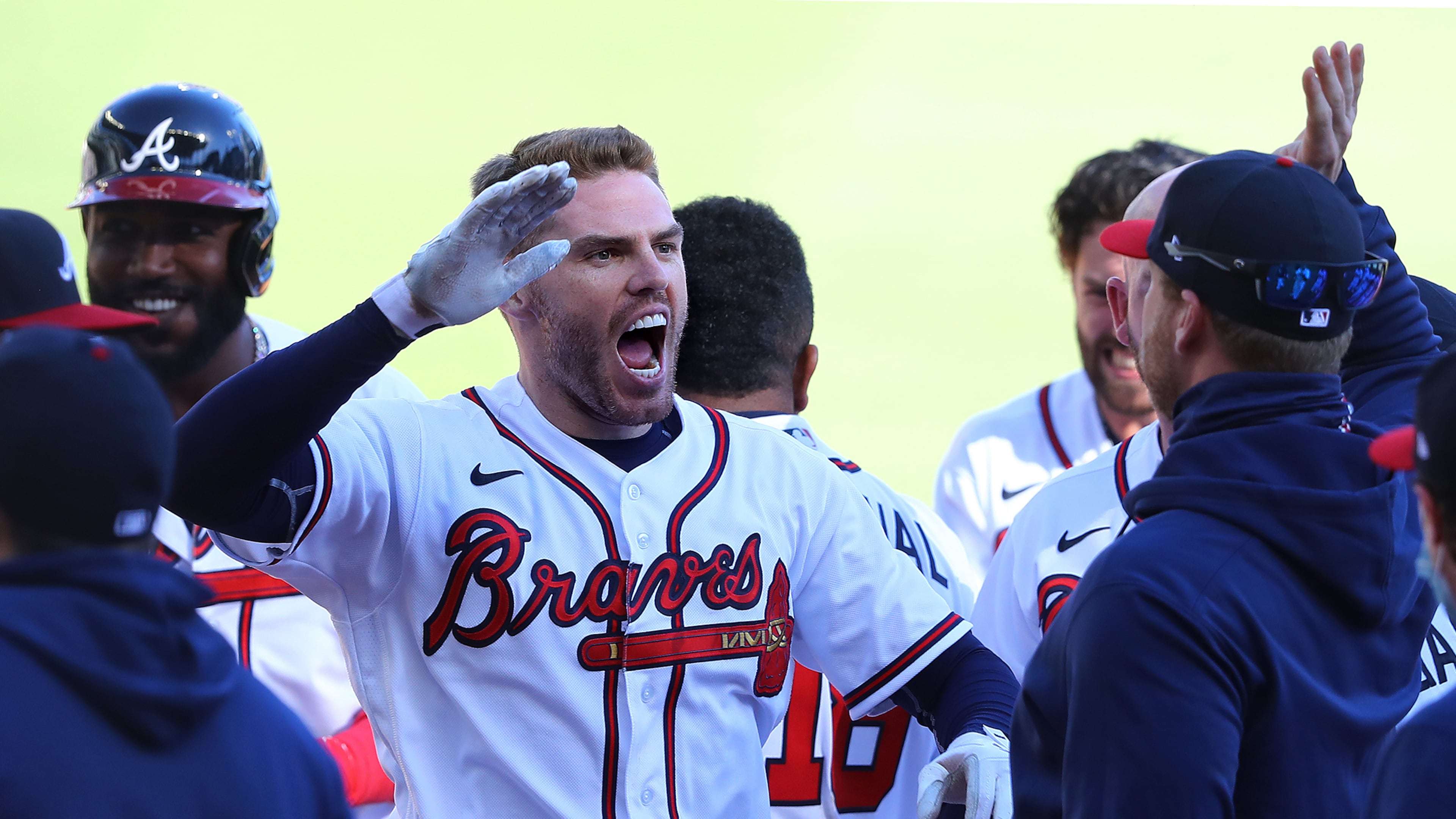

The next year was different. On Sept. 25, 2012, Freeman hoisted a walk-off home run against Mike Dunn that clinched the wild card for the Braves. Chipper Jones scored ahead of Freeman that night. Jones would retire at season’s end.

By the end of the 2013 season, Freeman had become the Braves' best hitter – ahead of Heyward, ahead of the much-ballyhooed Justin Upton. On Feb. 4, 2014, Wren signed Freeman to an eight-year extension for $135 million. That same day, Heyward accepted a two-year extension for $13.3 million. There were two reasons for this: First, Heyward wasn’t interested in signing away his free agency years, but also because Wren had decided only one of the two was apt to become a franchise cornerstone. The one was Freeman.

Heyward was traded to St. Louis in November 2014 by John Coppolella, Wren’s successor. A year later, Heyward reaped his free-agent windfall, signing with the Cubs for $184 million over eight seasons. Freeman became the only reason to watch some terrible-by-design Braves teams. The Braves had many chances to dump him for even more prospects. They rebuffed all. Said Coppolella: “I’ll cut off my arm before I trade Freddie Freeman.”

Somehow Freeman managed to stay cheerful during the tanking. Not incidentally, make himself an even better hitter. During batting practice in Milwaukee in the summer of 2016, he and hitting coach Kevin Seitzer stumbled onto something. If Freeman just tried to hit a grounder to shortstop – not a grounder past or a liner over shortstop, mind you – he invariably wound up hitting something far better. The act of trying to hit the ball on the ground made him keep his head down.

Said Freeman: “If you watch me, it’s the most boring batting practice ever. Some guys use their first two (BP) reps to hit the ball up the middle, and the last three they try to launch a little bit. I just try to hit a ground ball to shortstop.”

As of May 17, 2017, Freeman was on pace to have a Baseball-Reference WAR of 10.8, which would have trumped any season a Braves' non-pitcher – Aaron, Mathews, Murphy, Chipper – ever had. This correspondent was in the press box typing a numbers-laden paean to Freddie when, in grand Bradley Jinx tradition, Aaron Loup’s fastball smacked into Freeman’s left wrist. He would miss six weeks. He finished with a WAR of 4.7. The Braves went 72-90. He didn’t receive an MVP vote.

Then the Braves got good again. With better hitters around him, Freeman kept raking. His OPS over the past five seasons: .968, .989, .892, .938 and 1.102. He finished fourth in the MVP voting in 2018, eighth last year. Now he’s the National League’s Most Valuable Player.

He played all 60 games of this irregular season and hit .341, third-best in the bigs. He led the majors in runs. He was second in on-base percentage and slugging percentage, third in RBIs. He did this after missing much of summer camp because of COVID-19, which left him with a 104.5-degree temperature and, on the darkest night of his life, drove him to ask: “Please don’t take me yet.”

When the swimmer Mark Spitz won seven gold medals in the 1972 Olympics, a teammate said: “It could have happened to a nicer guy.” The next person to offer an unkind word about Freddie Freeman will be the first. He’s a great player. He’s a great teammate. He’s a great guy. In our flawed world, virtue and excellence aren’t always rewarded. This time they were.