It has been 23 years since the last — and only other — time the Braves and Marlins met in a playoff series. And to this day still, geometrists and civil engineers are trying to fathom the dimensions of Eric Gregg’s strike zone.

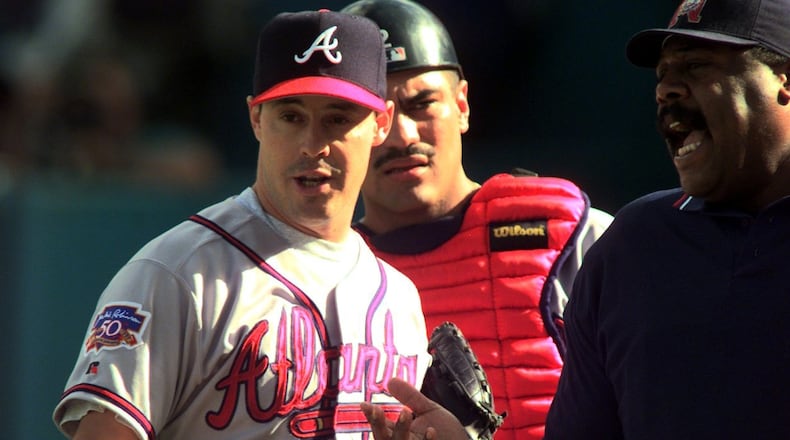

Oct. 12, 1997, is a date that lives in oath-spitting infamy for Braves fans. Then, during a pivotal NLCS Game 5, the Miami, nee Florida, Marlins beat the Braves and Greg Maddux 2-1 behind a record 15 strikeouts by the crafty Livan Hernandez. A few of those strikeouts may even have been legitimate.

For from behind the plate that evening in Miami, Gregg, a wide man who had a wide strike zone, dead since 2006, seemed to expand the plate from 17 inches wide to include portions of suburban Hialeah. The heavily left-handed Braves lineup had no hope of reaching some of those pitches that bent outside the plate and into the catcher’s mitt. And Hernandez just kept working that fringe, teasing and tormenting the Braves hitters.

The game’s last pitch was a perfect summary of the night, never crossing the plate, seeming to arc a good foot outside. The count was full. As Fred McGriff prepared to discard is bat and take his walk, Gregg instead rang up strike three. Game over, called on account of a Twilight Zone for a strike zone.

Sure the Braves whiff plenty now. They just got through striking out 35 times in two days against Cincinnati. And there certainly were other reasons they lost that ’97 NLCS, including some shoddy fielding in Game 1 and Tom Glavine yielding seven runs in the first six innings of the deciding Game 6. But the so-called Eric Gregg Game will forever occupy a particularly dark corner of Braves history.

With that win, the Marlins took a 3-2 lead in the series. They put it to sleep the next game and went on to win a World Series.

Due in part to the Gregg Game, the Marlins forged a legacy of never losing a postseason series (they’re 7-0 coming to Tuesday’s Division Series meeting with the Braves). While the Braves have gone 5-13 in postseason encounters since then.

Which poses the question: Would you rather be a franchise like the Marlins that has infrequently made the postseason, but still possesses two world titles. Or be the Braves, who except for a recent four-season gap, have habitually provided fans a postseason experience to win only the one championship?

As division neighbors, the Braves and Marlins naturally import some shared history to his Division Series. That includes a nasty habit of hitting Ronald Acuna with thrown balls and the Braves scoring a modern-day record of 29 runs against the Marlins just a month ago.

The Eric Gregg Game remains a chapter unto itself.

As the Braves and Marlins intersect again in the postseason, we remember the words of Chipper Jones from 1997: “I’m so mad right now, I can’t see straight. Some people work their whole lives to get into this situation, and when you’re not allowed to do your job ...”

Mindful of the fact that Hernandez’s mound opponent that night — Maddux — often benefitted from a generous strike zone, then Marlins manager Jim Leyland said at the time, “I’ve watched a lot of Braves games on television over the years and managed a lot of games against them, and their pitchers always get a lot of called strikes on pitches that seem to be outside. So if we did, too, I would say that made it fair.”

That game will forever be a reference point for all future suspect games behind the plate. The question of how much of the complaining was warranted and how much might have been whining even inspired one scholar at FanGraphs to try to give the game some root in quantifiable fact.

He wrote: “Hernandez threw 143 pitches, and 88 of them were strikes. Of those, 37 were called strikes. That regular season, 29% of Hernandez’s strikes were called. In Game 5, 42% of Hernandez’s strikes were called. The other starter in Game 5 was Greg Maddux, and he struck out nine batters in seven innings. That was well above his regular-season rate. But 29% of his strikes were called, against a season rate of 28%. It’s not a great measure but that hints at a more favorable strike zone for Hernandez.”

The current group of young starters who have propelled the surprising Marlins to this second step of the Pandemic Playoffs are all hard-throwers and not inclined to nibble like Livan Hernandez. Nor are we ever likely to see anyone throw 143 pitches in a game this week.

That said, we’ll add that the Marlins will need none of help they got in 1997 to make this a trying series on the Braves.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured