It was a Friday in South Bend, Ind., and Georgia Tech’s football team had arrived by bus at Notre Dame Stadium for a light workout before it was to line up against the Fighting Irish the next day.

Dave Fagg, quarterbacks coach for those 1977 Yellow Jackets, recalls stepping off the bus and approaching a stadium gate to ask an employee to let the team in.

"He said, 'Hey, coach. Ain't nobody ever worked out in this stadium on Friday,'" Fagg said this past week. "Nobody. And we're not going to start with Georgia Tech.' "

Fagg returned to the team bus to report back to coach Pepper Rodgers, unsure of how his boss would respond. Rodgers ordered the buses to take the team to a neighboring greenspace in front of what is now known as Hesburgh Library. The library’s façade facing the stadium is recognizable to any college football fan, the mural known as Touchdown Jesus.

“We got off, we worked out right there on the promenade,” Fagg said, laughing at the 44-year-old image in his mind. “Looking right up at the library and Touchdown Jesus.”

Georgia great Vince Dooley had a memory of his own to share about Rodgers, who died May 14 at the age of 88 following complications from a fall that ruptured an artery in his head. They were rivals but friends – "I had always enjoyed being around him," Dooley said – and Dooley recalled walking through a hotel lobby at the annual American Football Coaches Association convention with a few coaches, including Rodgers. As usual, the lobby teemed with coaches.

"And he said, 'All of you have to excuse me. I've got to go page myself,' " Dooley said. "And sure enough, next thing we heard, 'Phone call for Pepper Rodgers, coach Pepper Rodgers.' That was him, always having a good time."

A performer from the start

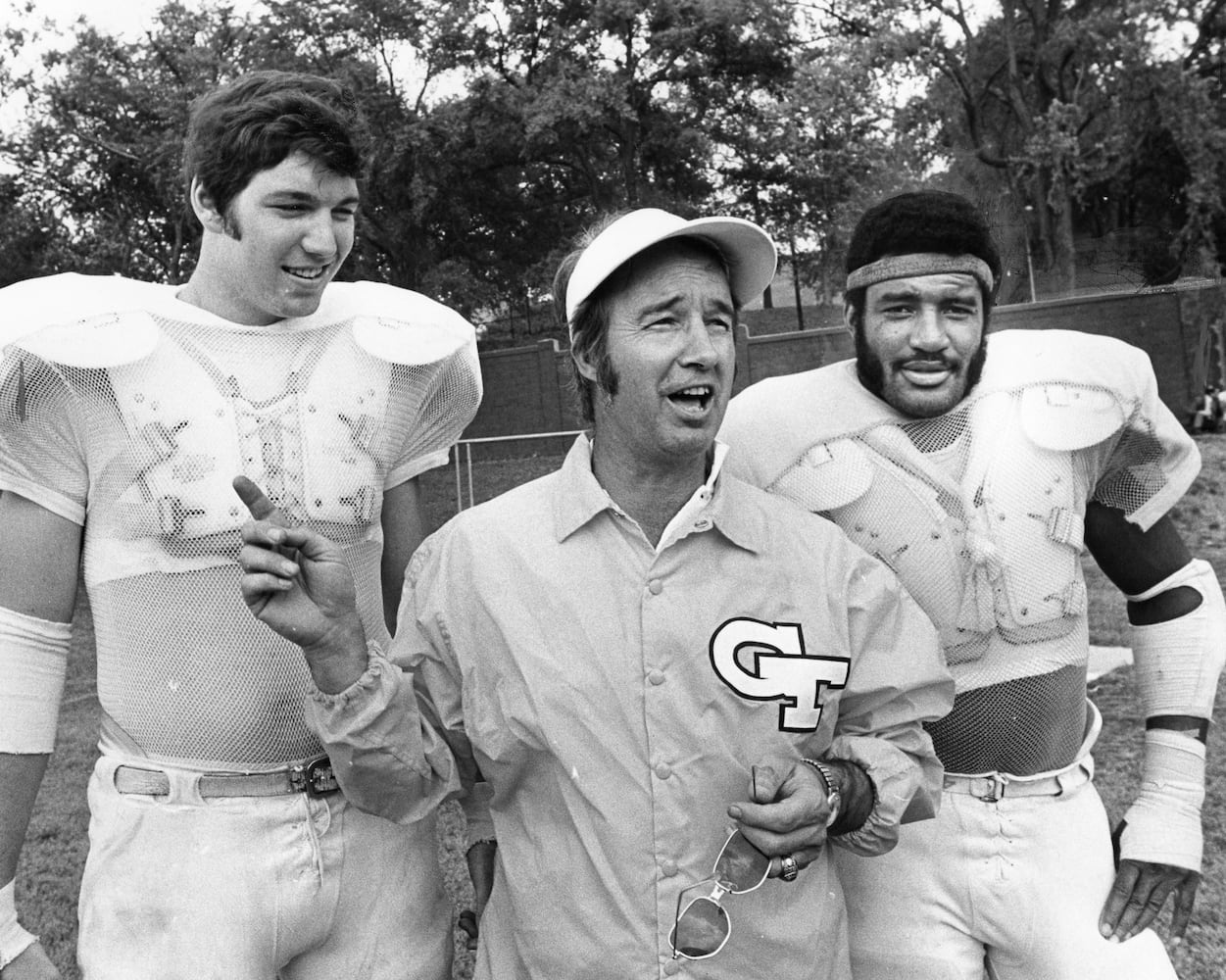

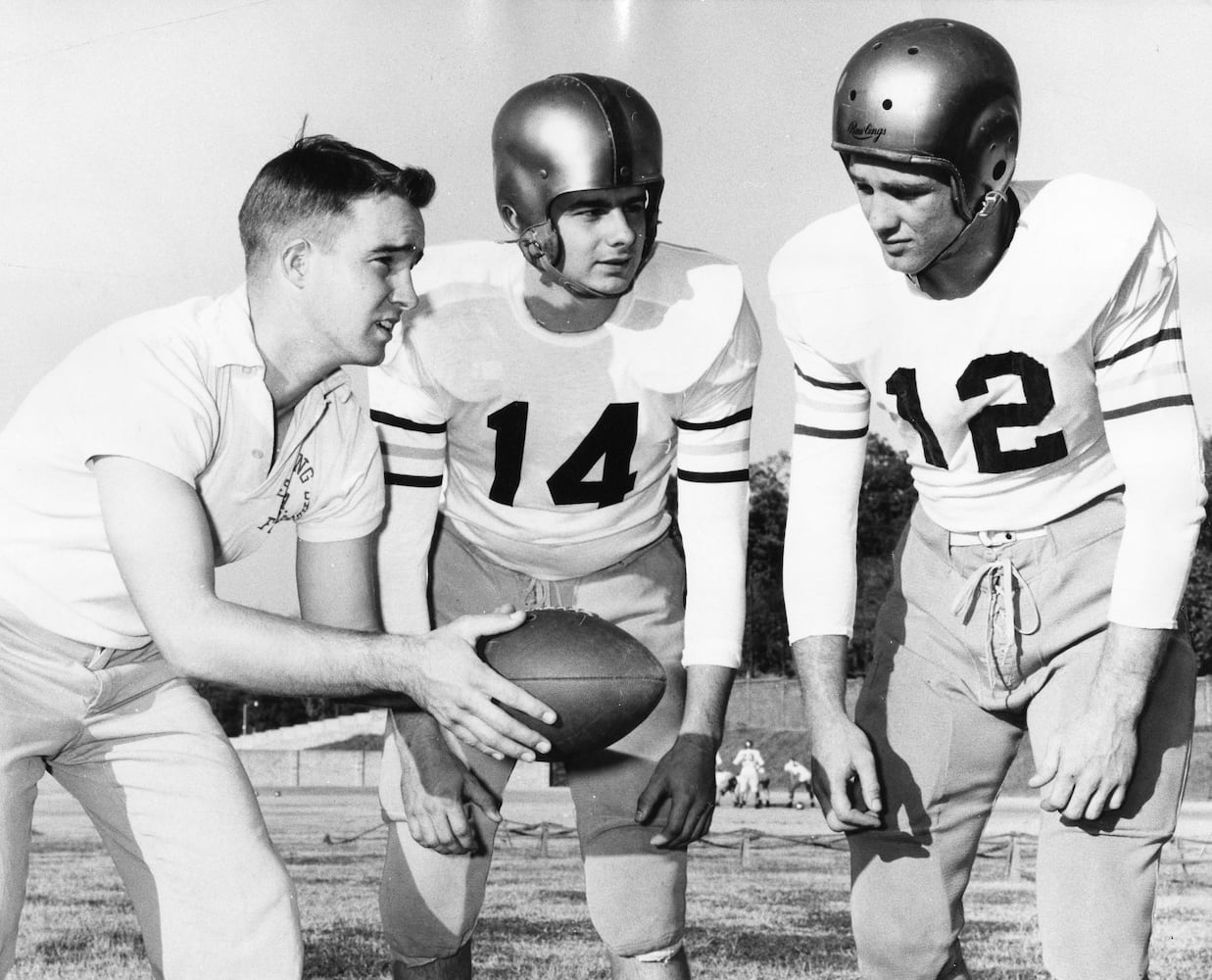

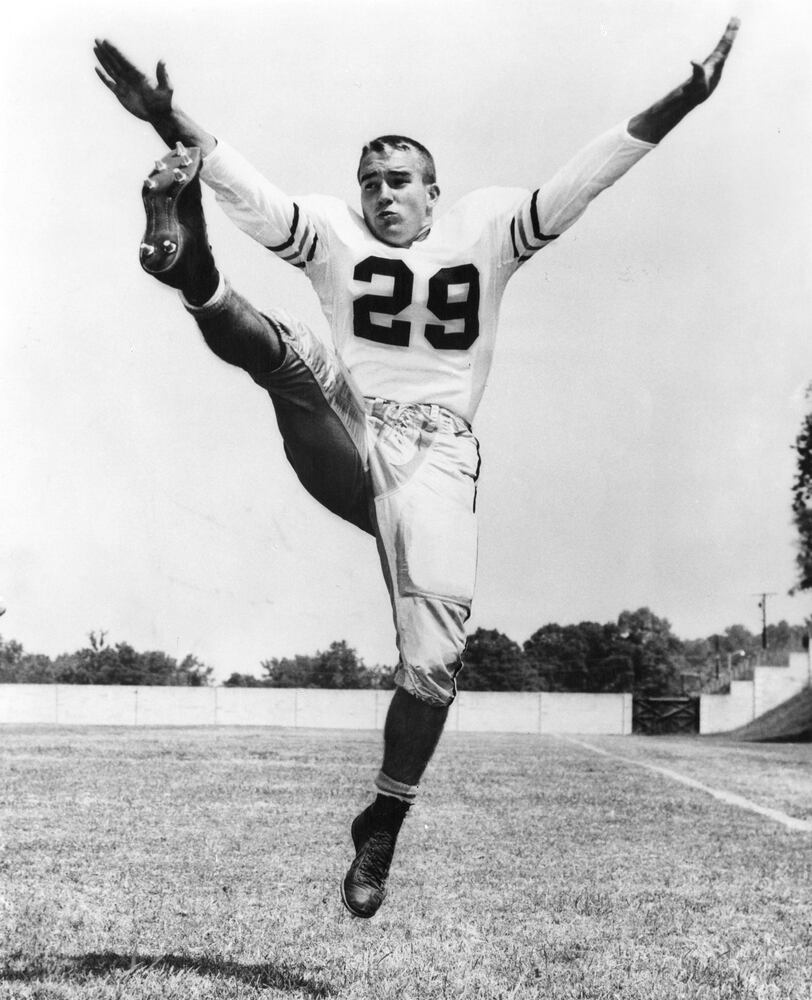

Standing out was no challenge for Rodgers, who quarterbacked and kicked on Tech’s shared national championship team in 1952 and returned to coach the Jackets from 1974-79. Even as a young child, he found the limelight, singing and dancing on the stage of Loew’s Grand Theater in downtown Atlanta as part of a fundraiser, performing in the same hall where “Gone With the Wind” premiered in 1939.

His singular personality helped his star to rise as a Tech player – he talked his way into a scholarship to Tech as a senior quarterback at Brown High, starting a career that ended with him winning game MVP honors at the 1954 Sugar Bowl – and later as a coach at Kansas, UCLA and Tech, earning six coach-of-the-year awards in 13 seasons, two at each school. It also proved part of his downfall at Tech, a surprise termination that led to Rodgers filing suit against the athletic association. To those who knew him, he was not easily forgotten.

"He truly was one of a kind," said Steve Raible, a tight end for Rodgers who went on to a six-year NFL career and is nearing retirement after an award-winning career as a news anchor in Seattle. "All those sayings you can think of, 'Marches to his own drummer,' all that kind of stuff, that was Pepper."

Raible holds vivid memories of warming up before games and seeing Rodgers up in the Grant Field stands, interviewing students for his TV show. At the time, a coaches program generally consisted of him narrating game highlights. On his, Rodgers interviewed the likes of entertainer Bob Hope, chef and TV personality Julia Child and the Allman Brothers Band. At a time when most games were not on television, it may have irritated fans who actually wanted to see the game, but was popular nonetheless.

“It’s my understanding that people saw it in Montreal, Mexico City and in the Caribbean,” said former Tech administrator Jack Thompson, who headed up recruiting for Rodgers and also produced his show during his decades-long tenure at the institute.

Raible also recalled doing headstands during pregame warm-ups on the field.

“It made your neck strong, but here we are, a group of about seven or eight of us in a circle, standing on our head in pregame,” he said. “It was just kind of weird stuff like that, but there was a reason for all of it.”

‘Ahead of his time’

Rodgers endeared himself to players by liberalizing rules to live off-campus. Raible recalled how Rodgers let players sleep in their own beds on Friday nights before home games rather than go to a team hotel, trusting them to choose rest over carousing. Raible called his coaching style “ahead of his time.” He was, perhaps, a player’s coach long before the idea gained currency in sports culture.

Arguably the best player that Rodgers recruited, running back Eddie Lee Ivery spoke of Rodgers with gratefulness. When he wanted to play through an ankle injury in his final game of his career (the 1978 Peach Bowl) to help his draft stock, Rodgers refused to let him play, fearing he could risk his NFL career, a seeming precursor to what would become common 40 years later, collegians sitting out their final bowl games. Without their All-American running back, the Jackets lost the Peach Bowl to Purdue 41-21, but Ivery became a first-round pick.

It followed a game earlier that season when Rodgers did the opposite, sending him back into a blowout win over Air Force so he could break the NCAA record for rushing yards in a game, finishing with 356 yards. To Ivery, both were examples of the care and love that Rodgers showed him.

“I hate to think where my life would be if I hadn’t chosen to play football for coach Rodgers, who taught me so much on the field and off the field also,” said Ivery, who is an assistant coach and parental involvement coordinator at Thomson High, his alma mater.

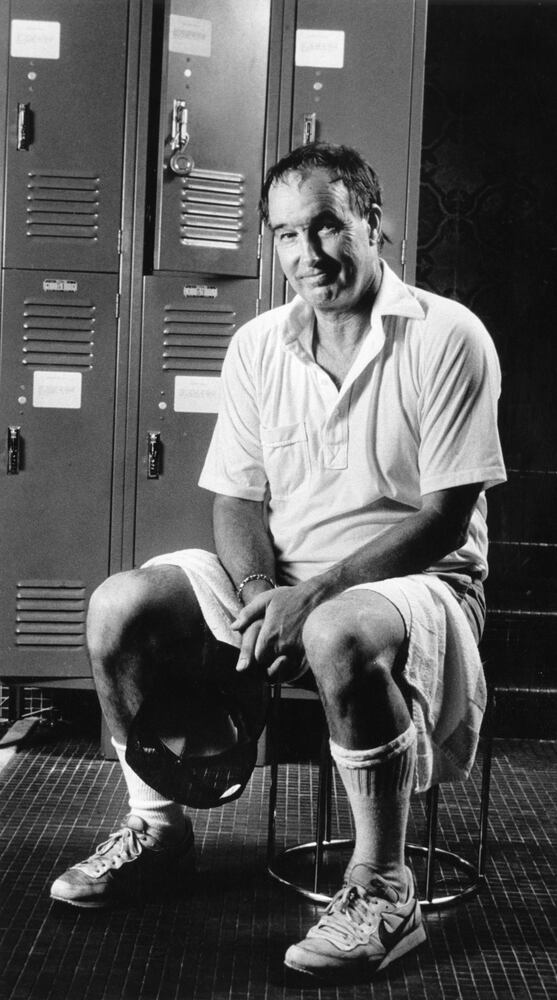

Rodgers created a distinct image with fans. When he arrived at Tech from UCLA, he wore his hair in a perm. He rode a motorcycle to the office. He made waves by getting a divorce after his arrival at Tech and marrying an actress, Janet Lake Livingston. Bill Hartman, the longtime Atlanta sports anchor, called him the most quotable Atlanta sports figure of the time.

“He was so different than the Braves manager, the Falcons coach or anything like that,” Hartman said. “He was just so different. And he had a lot of Hollywood to him.”

On the recruiting trail

Rodgers set himself apart in more practical ways. He instituted a weightlifting program, which Tech had not previously had, and stressed stretching.

More notably, where Tech had a handful of African-American players on the roster when he was hired in December 1973, Rodgers was unabashed in recruiting whomever thought could help, regardless of race. In 1975, he also hired Tech’s first two black coaches, Russell Charles and Bill McCullough, to be the running backs coach and strength coach, respectively.

“It didn’t matter to us what color you were, or where you were or anything else,” said Floyd Reese, the strength coach in Rodgers’ first season. “If you could play, we wanted you.”

The whole of Rodgers made for a winning recruiter. Early on in his tenure, Rodgers had his most success, landing the likes of Ivery, Lucius Sanford and Kent Hill, all of whom played at least eight seasons in the NFL. His 1975 signing class, the first he had an entire year to recruit, produced nine eventual draft picks, including first-rounders Ivery and Hill in the 1979 draft. It is one of only two times that Tech has produced two first-rounders in the same draft (2010 – Derrick Morgan and Demaryius Thomas).

Part of his recruiting schtick involved a 1974 movie, “The Trial of Billy Jack,” in which Rodgers had a bit part thanks to a friend, Tom Laughlin, who was the lead. Rodgers played a trooper who shoots the title character. On recruiting visits, Rodgers reenacted the scene, giving parts to the recruit’s entire family.

“It was the greatest,” said Reese, who went on to become the general manager of the Tennessee Titans during the Steve McNair era. “And I don’t think we ever lost a recruit with that.”

How his tenure unfolded

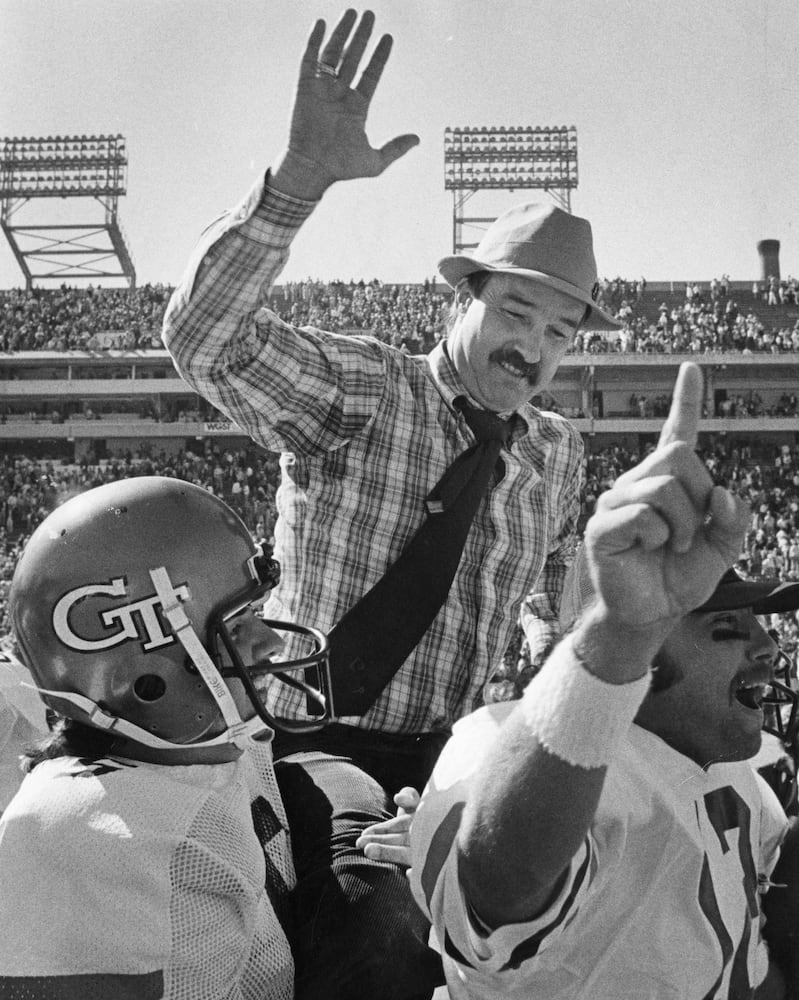

The start of Rodgers’ tenure held promise. In his first season, the Jackets gave Georgia one of its most lopsided home defeats (34-14) in the rivalry’s history and then finished 7-4 in his second season. He was a master of his wishbone offense, setting defenses up for big pass plays and staying a step ahead of the opposition.

“He was an excellent coach,” Dooley said. “Very, very good.”

In his six seasons at Tech, Rodgers had four winning seasons, twice as many as his two predecessors (Bud Carson and Bill Fulcher) in a combined seven seasons. But he topped out at seven wins, hitting that mark twice.

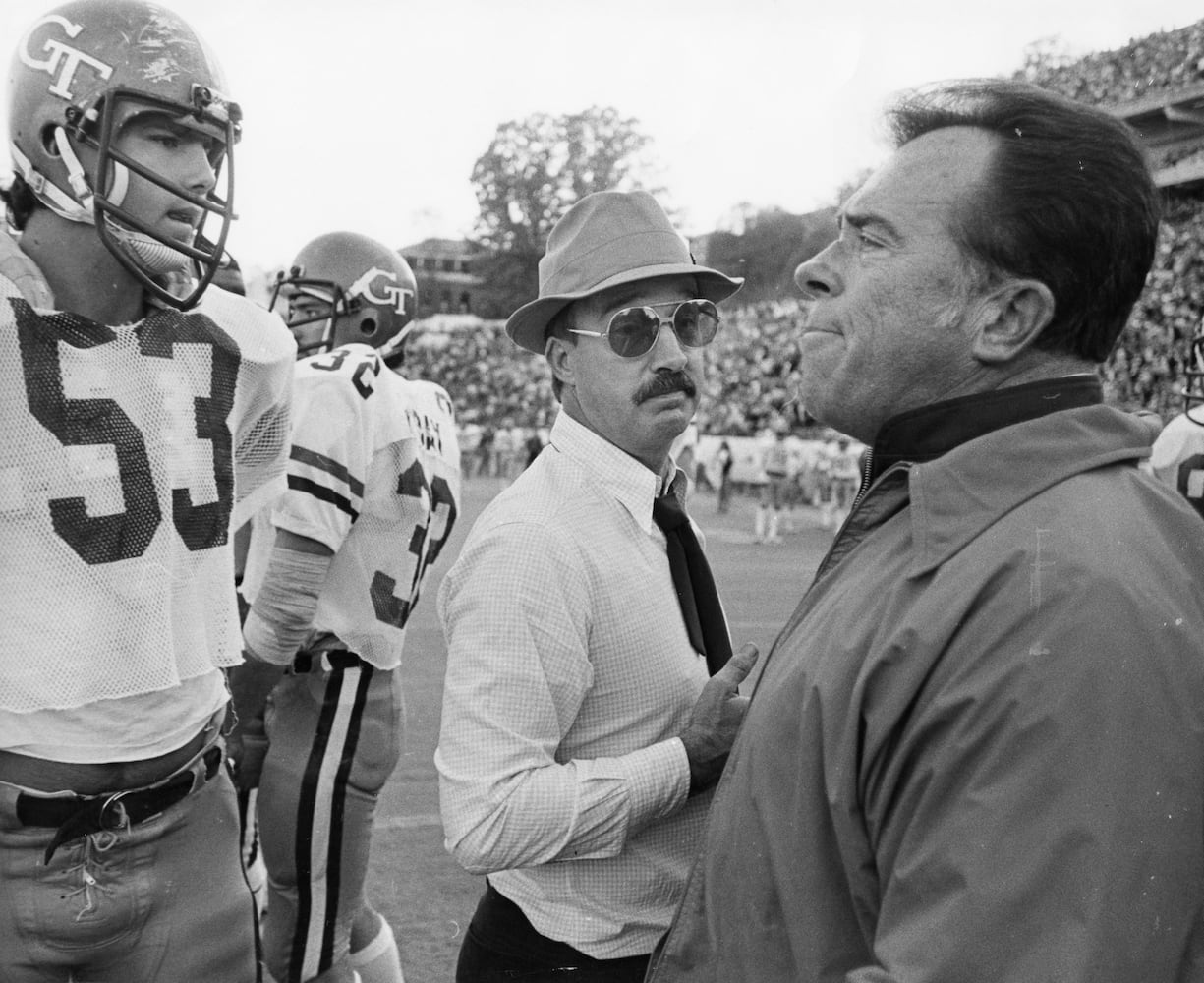

As his tenure extended and consistent success didn’t follow, the recruiting lagged. Those involved contend that Tech’s longstanding challenges of inadequate facilities and academic rigor factored significantly.

“It was incredibly hard to recruit at that time,” Thompson said. “I don’t think we had the worst facilities in the country, but we were close to it.”

Credit: Joe Benton / AJC

Credit: Joe Benton / AJC

In 1979, when Rodgers couldn’t break through in his sixth season – Tech was 4-6-1 – his iconoclast manner likely cost him his job.

“I think the players loved him,” said Thompson, who remained a close friend with Rodgers until his death. “All the alumni didn’t necessarily love him.”

He finished with a 34-31-2 record at Tech.

Let go with two years left on his contract, Rodgers then filed suit against Tech – his alma mater. He argued that he was owed more than the remaining base salary, including benefits like profits from his radio and television show and the use of a car and country-club memberships that were agreed on, but not written into his contract.

The suit was not settled until 1983, when Tech gave him a reported $100,000, less than a third of the $331,000 he originally sought. It likely changed how college coaching contracts were written, enabling coaches fired before the end of their contracts to receive what they were originally offered.

“It took nerve to do what I did,” Rodgers said at the time. “I knew it was an injustice, and I wanted to do something about it.”

In the end

It was a bitter way for his dream job to end. He never coached again at the college level, later coaching three seasons in the USFL and CFL in the mid-’80s. He finished his career as vice president of football operations for the Washington Redskins, retiring in 2004. He lived the rest of his life in Reston, Va., with his wife. He gave first jobs to Tech Hall of Famer Bill Curry (later to be his successor), college football Hall of Famer Terry Donahue and Reese.

He hired Steve Spurrier (another hall of famer whom Rodgers had coached as an assistant at Florida) at Tech after he had been part of a staff firing at Florida in his first job.

“He gave me an opportunity to continue coaching, and so I was forever thankful for that, that’s for sure,” Spurrier said.

In the end, after the echoes of cheers have quieted, coaches leave behind a record, certainly, but also the memories and feelings of those left behind. Football may never again see his likes, a coach who lived his life on his own unique terms.

“He was entirely different than any coach I’ve worked with,” Thompson said. “He was incredibly good to me, and I loved him.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured