Former Georgia Tech assistant coach Darryl LaBarrie acknowledges that he made a costly mistake and dearly wishes he had the chance to do it over. But LaBarrie, who was cited for NCAA violations that investigators stated could constituted breaches of conduct of the highest order, also asserts that he is not guilty of everything that the NCAA has alleged.

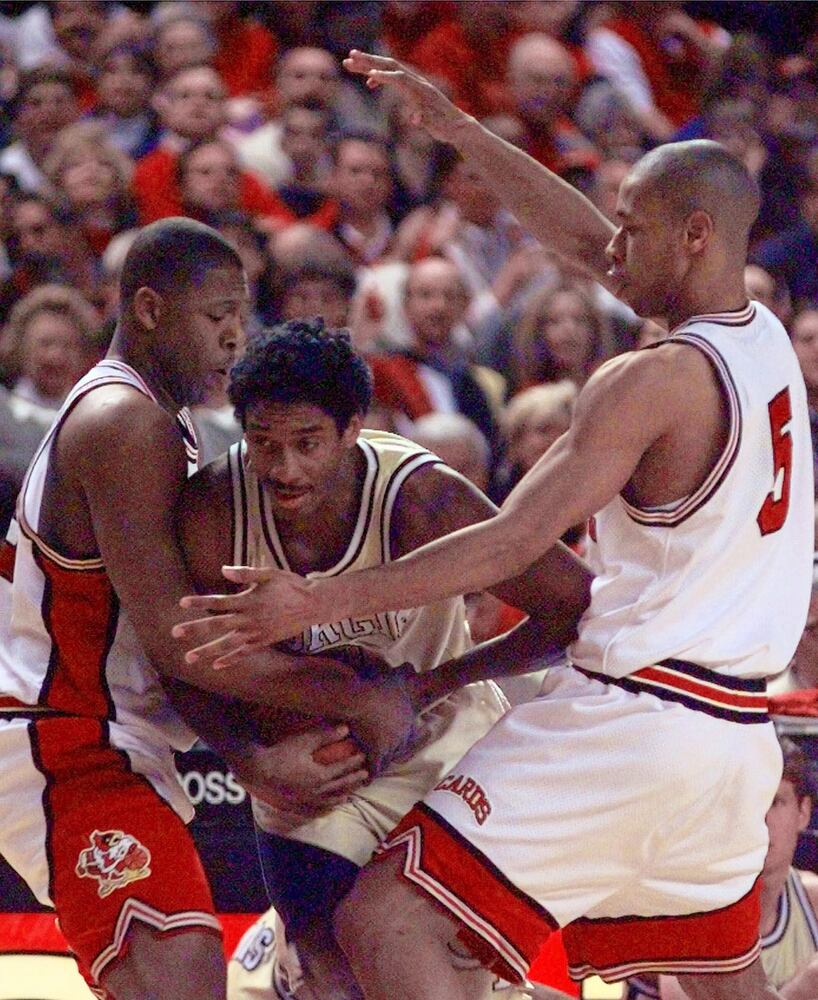

In an interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, LaBarrie acknowledged that in November 2016, he took a recruit and a team member to visit a booster – widely recognized as former Duke star and Pace Academy graduate Wendell Carter, former Tech player Justin Moore and former Yellow Jackets star Jarrett Jack – and then took them to a strip club.

“I would do anything to go back and change what I did on that night,” LaBarrie said. “It was just a lapse in judgment.”

But he also challenges what the NCAA also alleged and what he feels has become misunderstood in the public domain – that he had anything to do with Carter and Moore being given $300 to use at the strip club, or any awareness of such a transaction. Further, he said that he doesn’t believe that money was given to the two players at all, that Jack was the one who spent it at the club.

“When I was questioned about (a possible exchange of cash from Jack to Moore and Carter) was the first time I had ever heard, thought of, known anything about that,” LaBarrie said.

LaBarrie also owned up to lying to the NCAA when confronted about the matter a year later. He said, fuzzy on details of a memory he said he tried to suppress and panicked over being alone in a room full of NCAA investigators, he panicked and then, once he told his first fabrication, he felt he couldn’t fess up and come clean. But, then, of his own volition, he called the NCAA the next day to ask for a second interview, at which point he said he was completely truthful. He also said that another finding of the NCAA that is a significant violation – that he asked Moore to recant his version in order not to contradict LaBarrie’s first interview – is not true.

“It’s not the truth,” LaBarrie said. “And I said that in my second interview, that that did not happen.”

To some, LaBarrie’s version might appear to be window dressing. He took a recruit to a strip club and lied to the NCAA. To LaBarrie’s sympathizers, though, it is a case of a coach who had had a clean record for the entirety of his first 10 seasons as a Division I assistant coach, then made an egregious mistake, panicked and then sought to make his mistake right and is now paying a severe price, particularly when compared with others in the business who have committed far worse NCAA crimes.

“We’re talking about two hours out of a life that I’ve built to become the best person and coach that I could possibly be,” LaBarrie said. “And I made a mistake that lasted for two hours, and unfortunately, it’s harmed me for two years. It’s just a lesson. All I can do is learn from it.”

Tech put LaBarrie on leave Nov. 21, 2017, the day after his first interview with the NCAA. (LaBarrie said he asked for the second interview before the job action.) He resigned later that season – coach Josh Pastner’s second season coaching the Jackets – to avoid being a distraction to the team, he said at the time. The extended length of the investigation – a year and a half after since it began, with no clear end in sight – has impaired LaBarrie’s ability to return to college coaching.

For LaBarrie, who grew up in DeKalb County and then played at Tech for Bobby Cremins and Paul Hewitt, it has been an agonizing wait. LaBarrie said that schools have reached out interested in hiring him but are unable because of the uncertainty of how or when the NCAA will rule. If the committee on infractions finds the NCAA investigators’ version to be accurate, it won’t be a surprise if LaBarrie is served with a show-cause order, essentially a suspension from college coaching. LaBarrie has done some private coaching, tried to hook on as an NBA scout and even worked briefly at a Chick-fil-A, all the while he and his family have lived with the possibility of impending NCAA punishment over their heads. (LaBarrie also wanted to make clear that his alleged violations had nothing to do with those tied to Pastner’s former friend Ron Bell, a misconception created by the fact that the NCAA’s notice of allegations to Tech included both sets of alleged violations.)

“I just think that there have been stories that have been much worse, and much more serious, and I’m not taking anything away from what happened because I admitted that I made mistakes, and I should have handled things differently,” LaBarrie said. “I’ve admitted that to the NCAA, I’ve admitted that to Georgia Tech, I’ve admitted that today to you, but for it to still be dragging on three years later, for my family more than for myself, just seems unfair.”

LaBarrie has found himself waiting on the NCAA and Tech to bring the investigation to a close. Manny Arora, an attorney and Tech grad who is working with LaBarrie, expressed his frustration that he believes Tech can do more to help LaBarrie by expediting the investigation process.

“I think it’s, rather than backing him up and giving him the benefit of the doubt, it’s, ‘Cut him loose, get the attention off of us and let’s move on,’” Arora said. “That’s what’s soured me, being a Georgia Tech grad and having dealt with prior administrations, it’s a little unfortunate.”

Asked for his reaction to Arora’s assertion, LaBarrie responded, “You have a right to your opinion.”

In a parallel universe in which LaBarrie on the night of Nov. 5, 2016 had acted more like the goody two-shoes that his friends used to tease him of being, it’s not unreasonable to consider multiple possible outcomes, such as Tech’s recruiting being better (he had a tight relationship with star guard Ashton Hagans, who committed to Georgia before ultimately going to Kentucky). LaBarrie also was the architect of what has been the strongest facet of the team, its defense, and was the primary assistant coach for the best player in Pastner’s tenure, Josh Okogie. It’s not hard to imagine LaBarrie jumping to head-coaching openings at Georgia State or Kennesaw State.

But that is not his reality, one which he is hoping can brighten sooner rather than later. As for lessons learned, LaBarrie had a few.

“Something that you always know as you get older, every decision that you make is more powerful, more impactful,” he said. “Like I said, I wish I would have made a better decision that day. But I also learned in business, when things get hard, people take care of themselves. Which was a great lesson for me to learn. And I think it’ll make me a better person, coach, mentor moving forward.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured