On the day he snapped a photo that would be shared literally worldwide a century after he took it, Thomas Frederick Carter inhabited a world that sounds entirely familiar.

In Fall 1918, media reports provided daily updates on mortality rates of a pandemic. Schools, churches and other places of public gathering were closed. Volunteers assembled to make hundreds of masks. Businesses impacted by shutdowns waited eagerly for health officials to signal a return to life as usual.

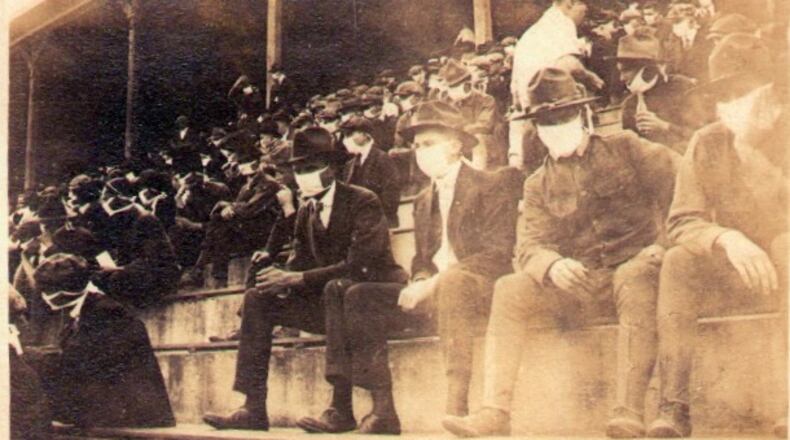

And, as Carter himself documented, sporting events tried to find their place in the midst of the Spanish flu contagion.

“Every time I see (the photo), it just reminds me what they had to deal with it back then, and we’re dealing with it now,” said Andy McNeil, a great-grandson of Carter who has a framed copy of the photo in his home office in Atlanta. “Similar circumstances.”

McNeil shared the photo with Tech, his and his great grandfather’s alma mater, and others, and it has crisscrossed the online world through social media and sports websites. The slice of pandemic life captured by Carter, who died in 1998 at the age of 98, has caught the attention even of those in college football’s highest offices. West Virginia athletic director Shane Lyons, chair of the Division I football oversight committee, referenced the photo in a recent interview about the return of college football.

“They always say history repeats itself,” Lyons said. “Well, that may be what (the) 2020 college football season looks like.”’

Life in 1918

What else was happening on that fall afternoon when Carter pointed his lens up into the Grant Field stands, full of well-dressed fans with masks strapped to their faces?

In October 1918, as the Allies neared victory in World War I in Europe, the Spanish flu outbreak swept across the U.S. It would eventually kill 50 million people worldwide and 675,000 people in the U.S., about one out of every 200 Americans. Victims sometimes died within hours of the onset of symptoms.

On the seventh day of the month, in an attempt to control the epidemic, Atlanta’s city council ordered all schools, churches, movie theaters, vaudeville houses, dance and billiard halls closed for two months. Two doctors on the city’s board of health warned of being overwhelmed by patients.

Dr. J.P. Kennedy, the city’s health officer, warned in the Atlanta Constitution that “I can see no chance of controlling it unless we resort to the closing of these places. It looks like we are going to have a serious epidemic.”

The order, though, did not include an impending fair and pageant, on account of their being held outdoors.

Open-air gatherings, such as football games, were evidently approved. Schools held meetings in advance of school-board elections outside the schoolhouses. At Camp Gordon, an Army training camp on the site of what is now DeKalb-Peachtree Airport, soldiers slept outdoors.

With school suspended, a letter to the editor suggested that schoolboys “go out in squads to the nearby country farms” and help gather the cotton crops.

‘Bandits of a mild sort’

In that setting, the powerhouse Golden Tornado (as the Yellow Jackets were then known) continued with their season. McNeil does not know at which game his great grandfather took the photo. However, the Constitution reported that the Oct. 12 game against Furman drew to Grant Field “many students, looking, in their influenza masks, like bandits of a mild sort.”

The Furman game was Tech’s first after the city-wide closure of schools, churches and the like. (It would appear that Tech itself was not closed, although the University of Georgia was put under quarantine the same day that Atlanta gathering places were. Bulldogs fans may also recall that the school did not field a team during the war years of 1917-18.)

The Constitution’s description would match the subjects of the photo taken by Carter, a mechanical engineering student. Tech fans were far from the only Atlantans wearing masks. They also were required attire at the popular Southeastern Fair held at the Lakewood Fairgrounds held in October. The Constitution reported that “it was a sight to behold an unmasked person and when one was found he was usually held in disdain by the crowd.”

According to other newspaper accounts, masks at sporting events were not uncommon, sometimes required. In Missouri, two military academies played a football game in which the players themselves were masked.

At Tech, in fact, masks weren’t the only precaution taken. The Oct. 10 edition of the Constitution apprised readers of another measure ordered by army medical authorities at the school to prevent the spread of the contagion at football games – no cheerleading.

“Cheering is too much like sneezing: if it is to be done in these days of influenza, it should be done through a handkerchief, and a cheer through a handkerchief would not be worth doing,” writer J.H. McKee reported. “So there will be no cheerleading.”

The article added that no authority “could prevent the occasional individual yell of the true enthusiast” and also that “there will be no ban on the projection of hats into the air.”

Canceled games nationwide

The confluence of the epidemic and the war made for an odd season. The epidemic caused a slew of canceled games, but so did a decree from the U.S. war department made at the end of September. It mandated that, in October, teams with units of the Student Army Training Corps could not play games that required them to be away from campus overnight. (The SATC was a war-department program in which students took classes and trained for the military while compressing the track to a degree. It was disbanded after the armistice.) In November, teams could leave campus Friday, but had to be back within 48 hours.

That ruling punched gaping holes in schedules, including Tech’s, which had to forgo a November road trip to Philadelphia to play Penn.

Games against teams representing army training bases became a popular fallback. Tech played seven games that season, including matchups with the 11th Cavalry (stationed at Fort Oglethorpe in North Georgia) and Camp Gordon.

As the Constitution reported after the game with the 11th Cavalry was scheduled, “athletic authorities at the school leave no stone unturned and no telegraph wires unheated in endeavors to get games.”

Besides scrambled schedules – acknowledged as a possibility for the 2020 season –there were plenty of other notes from that season that resonate 102 years later. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the cancellation of the Penn-Tech game was fortuitous because Penn would have owed Tech a $5,000 guarantee, a sum it might not have been able to recover given the potential for lower attendance. It’s a reminder of the role that money has played in college football virtually from its start.

Coaching carousel rumors also flew. After the season ended, there were reports that Tech coach John Heisman was to leave the school for a job in the Northeast and also that Georgia, perhaps trying to match the powerhouse built by its in-state rival, had offered Pitt coach Glenn “Pop” Warner (a former UGA coach) a three-year contract worth $10,000 annually.

(Both Heisman and Warner stayed put, although Heisman left Tech a year later on account of a divorce and ended up at Penn, his alma mater.)

There was even the intersectional rivalry that still fuels the game. Tech and Pitt scheduled a titanic matchup for Nov. 23 in Pittsburgh as a fundraiser for the War Work Fund, created to boost morale for American military stationed in Europe after the war, in which fighting ended Nov. 18.

Tech players traveled north even with the good wishes of Auburn, Alabama and even Georgia, the Constitution reported.

Wrote the Constitution, “All rivalry is forgotten when the south as a whole is affected.”

Or, in other words, “SEC! SEC!” (Tech and Georgia were both members of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, a forerunner of the SEC.)

As for the Tech-Pitt game, it brought together the 1916 national champion (Pitt) and the 1917 national champ (Tech), the first Southern team to earn that distinction. The Tornado was unbeaten in 33 games, including the 222-0 win over Cumberland in 1916. The Panthers, meanwhile, had a 27-game unbeaten streak.

Tech’s lineup included left end Bill Fincher, left halfback Buck Flowers and right halfback Joe Guyon, all of whom would be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame along with Heisman.

“GRIDIRON TITANS TO BATTLE” screamed the headline of the Pittsburgh Press on the day of the game. But it was not to be for Tech. Before a crowd of 30,000 and a host of writers from New York, the Tornado bowed 32-0 to the Panthers.

By that time, the public gathering ban had been rescinded on Oct. 25 by the Atlanta city council following debate that may also strike a chord. Atlanta’s board of health was split on whether to recommend that the city council rescind its order prohibiting public gatherings. While Kennedy (the city health officer) recommended the ban be lifted, two other doctors on the board asserted conditions had not sufficiently cleared, one saying that not all the influenza cases had been counted.

Speaking on behalf of city theaters, a city councilman advocated for a reopening. When the board proposed putting the matter off until Nov. 2, Mayor Asa Candler, founder of Coca-Cola, pushed back on the grounds that it was impossible to know what the conditions would be like in a week’s time. The city council voted 19-4 in favor of rescinding the ban. Theaters, dance halls and churches were quick to reopen. Athens ended its quarantine for UGA the same day.

Was it effective? According to the Influenza Encyclopedia, produced by the University of Michigan, Atlanta's epidemic death rate of 414 per 100,000 people was about average for cities in the South and Midwest.

Among those likely eager to return to a life of relative normality was a mechanical engineering student at Georgia Tech. Thomas Frederick Carter may have even projected his hat into the air.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured