Warnock goes on offensive to disarm attacks

Editor’s note: This updated profile of the Rev. Raphael Warnock is part of a series of stories about the candidates running in Georgia’s U.S. Senate runoff elections on Jan. 5. Another story focuses on Warnock’s opponent, Kelly Loeffler. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has also published profiles of the candidates in the state’s other Senate race, Republican David Perdue and Democrat Jon Ossoff.

The Rev. Raphael Warnock — who had never run for a political office — knew the hits were coming.

So just days after he had secured the most votes in a contentious 21-candidate race for the U.S. Senate, winning a spot in the Jan. 5 runoff against well-financed Republican incumbent Kelly Loeffler, Warnock released an attack ad — against himself.

The effete way he eats pizza with a knife and fork.

His hatred of puppies.

It was funny and deeply ironic. But it offered a warning to Warnock’s supporters and people in the middle that Loeffler was coming.

After Warnock, a Democrat, went largely untouched during the first round of voting ― while Loeffler and her main Republican challenger, U.S. Rep. Doug Collins, battered each other for the heart of the party’s base and that of President Donald Trump ― the GOP mined his past sermons, affiliations and stances to launch a series of hard-hitting attacks against the Ebenezer Baptist Church pastor.

Loeffler has called Warnock “the most radical and dangerous politician in America,” and aside from her volley of negative ads, a host of high-profile Republicans including President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence have visited the Peach State to convince Georgians that the Democrat is too extreme for Georgia.

That he hates the police and military, and he palled around with Fidel Castro and the Rev. Jeremiah Wright. Days before coming to Atlanta to campaign for Loeffler and Sen. David Perdue, who is in his own pitched battle against Jon Ossoff, Trump said Warnock “is either a communist or a socialist.”

“I can’t figure that one out yet, but he’s either a communist or a socialist, probably a communist,” Trump said. “This is not for Georgia.”

In his ad that came out right after the election, Warnock said: “Kelly Loeffler doesn’t want to talk about what she is for — getting rid of health care in the middle of a pandemic — so she’s going to try to scare you with lies about me. And by the way, I love puppies.”

Warnock’s Twitter timeline has almost as many photos of dogs as there are of him.

Warnock is attempting to make history by climbing out of Savannah’s Kayton Homes projects to become Georgia’s first Black U.S. senator and just the 11th African American to serve in the Senate since Hiram Revels was elected to represent Mississippi in 1870.

Before launching his Senate bid, the 51-year-old Morehouse College graduate had decent name recognition as the pastor of Ebenezer, the historic home church of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Early polls show Warnock, who raised more money and got more votes than any other candidate in the general election, in a virtual tie with Loeffler, who is largely self-financing her campaign.

Warnock is not accepting corporate PAC money but has become a constant presence on television through his ads and guest appearances on major cable news networks.

During the first round of the election, Warnock’s campaign benefited from the bitter Republican-on-Republican feud between Loeffler and Collins, which distracted GOP attention away from attacking his record.

He did face criticism in April, but that was from Democrat Ed Tarver, who called on the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee to rescind its endorsement of Warnock after news broke about a minor domestic incident between the pastor and his then-wife.

But as Warnock rose in the polls, and now that he has made it to the runoff, Republicans have tried to use his words against him.

The GOP began circulating video from 2013 of Warnock describing capital punishment as “part of a conservative backlash in the years immediately following the civil rights movement.”

”In a real sense, it is the final fail-safe of white supremacy, for the data clearly show that its use ensures that in the final analysis, the lives of white people are to be regarded as more valuable than the lives of Black people,” Warnock said in the speech.

Warnock has long opposed the death penalty and was a leading advocate for Troy Davis, who was executed in 2011 in the slaying of a police officer despite evidence that supported his innocence.

In his messaging and on the campaign trail it is easy to see how the gospel according to Warnock is playing out. He has said several times that, now more than ever, the Senate needs a pastor.

“We are at an inflection point in American history," Warnock said. "There is a fundamental question about the character of our country and the soul of our nation. We are in a spiritual crisis.”

Spiritual crisis or not, the attacks keep coming, and Warnock and his followers have to spend a good bit of time responding.

In one tweet, Loeffler said Warnock “has a long history of anti-Israel extremism.”

“He defended Jeremiah Wright’s anti-Semitic comments,” she tweeted. “He embraced the anti-Zionist (Black Lives Matter) organization. And he thinks Israel is an ‘oppressive regime’ for fighting back against terrorism.”

In an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Rabbi Peter Berg, the leader of The Temple, Atlanta’s oldest Jewish congregation, and a friend of the minister, said, “The recent attacks against Rev. Warnock misrepresent his position on Israel.”

'Ability to see things differently’

As Loeffler continues to court Trump and other conservatives, Warnock has comfortably settled into his liberal platform focusing on expanding access to health care, protecting voting rights, fighting for worker rights and addressing criminal justice. As a pastor, he has spent his life at bedsides and in hospitals tending to the sick and dying.

In June, shortly after preaching at the funeral of Rayshard Brooks, a Black man killed by an Atlanta police officer, Warnock headed to South Georgia to welcome the release of his brother Keith, who in 1997 was sentenced to life in prison for a nonviolent drug-related offense.

The son of two pastors, Warnock is the 11th of a dozen kids and the first to go to college. In 2005, at age 35, he was tapped to lead Ebenezer. Shortly after arriving he led a “Freedom Caravan” of Hurricane Katrina evacuees back to New Orleans to vote in person.

It was then that state Sen. Nan Orrock met Warnock for the first time.

“I saw then a person very passionate about justice, voting rights and working to meet the needs of those who are in dire straits,” Orrock said. “Now, 15 years later, I am grateful that he is willing to plunge into this battle. He is a man of keen intellect, a strong work ethic and the ability to see things differently. That is needed in the U.S. Senate.”

Since becoming Ebenezer’s pastor, Warnock has led voter registration drives, advocated for the expansion of Medicaid, hosted a climate change summit with former Vice President Al Gore and pushed for an overhaul of criminal justice policy.

“It is about my passion for justice,” said Warnock, who recently marked his 15th anniversary at Ebenezer. “I am not in love with politics, but I am in love with humanity. Politics is a tool to effect the kind of change that I want to see in the world.”

Virus forces changes in pulpit, on campaign trail

Just six weeks into his campaign, the world stopped at the feet of the coronavirus, forcing Warnock to make his adjustment from the pulpit to the campaign virtually. Ebenezer has opened just twice since the pandemic ― for the funerals of Brooks and U.S. Rep. John Lewis ― so he tapes his sermons to be delivered on Sundays.

He can’t knock on doors, kiss babies or sit in living rooms. Instead, he does Zoom.

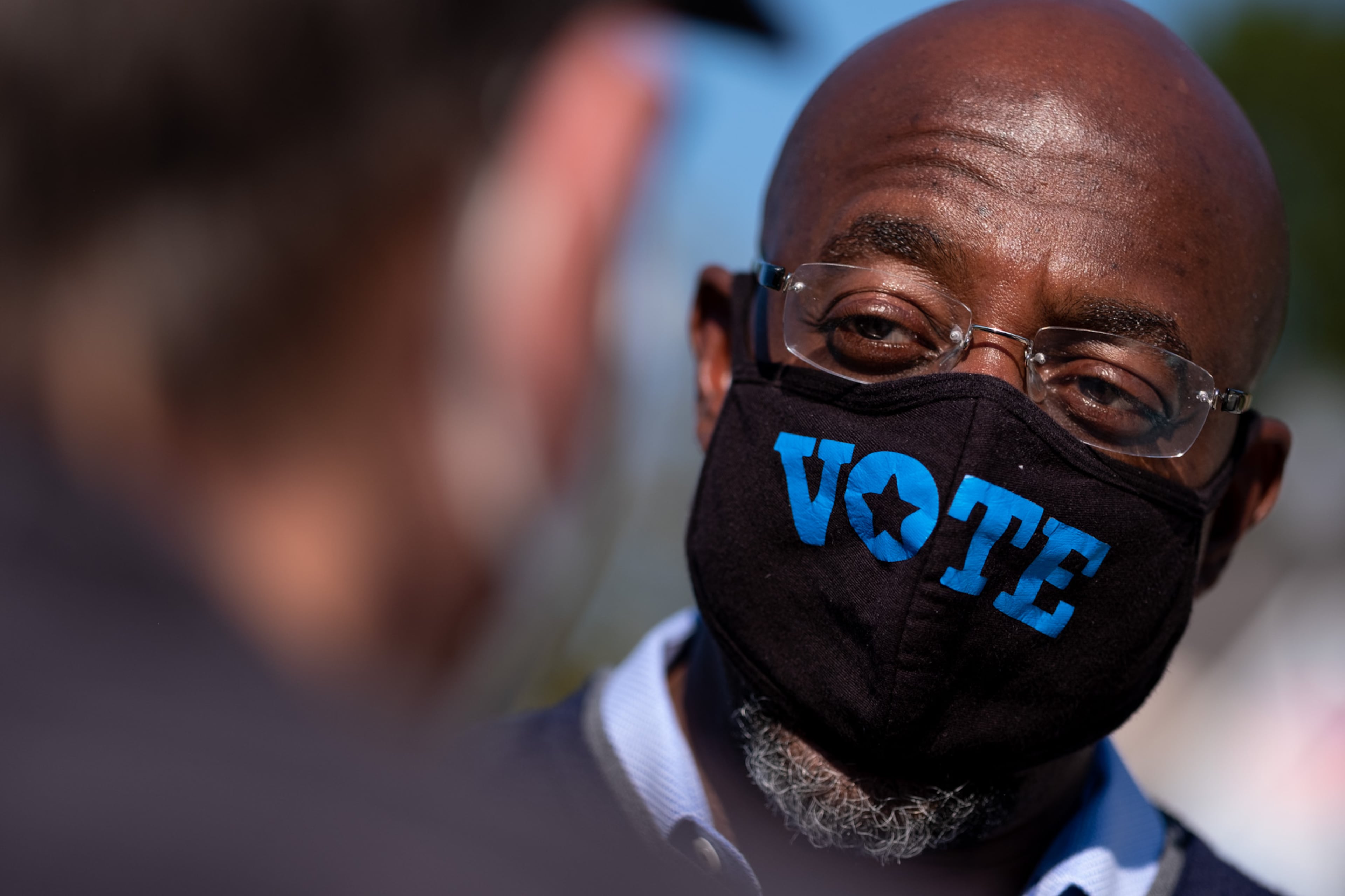

Rallies, increasingly alongside Ossoff, are carefully socially distanced, and everyone wears masks.

Monica Brookings Wells and her husband, Jonathan, who live in Powder Springs and are members of Ebenezer, showed up at a Powder Springs rally to hear Warnock. This was their first time seeing their pastor in person in months.

“If you have ever gone to one of his sermons, you will see how focused he is,” Wells said. “And that translates on the campaign trail. He sounds like what he needs to sound like, and he is going to stay focused.”

In a follow-up to his first ad, Warnock, wearing jeans, a blue shirt and a vest, is seen walking through a quiet neighborhood ― walking the dog.

“You would think that Kelly Loeffler might have something good to say about herself if she really wants to represent Georgia,” Warnock says. “Instead, she is trying to scare people by taking things that I have said out of context from over 25 years of being a pastor.”

Warnock pauses for a second and drops a small blue bag of puppy poop into the trash.

“But I think Georgian’s will see her ads for what they are,” he said.

The dog barks.