The more controversial the better for Greene’s fundraising, and her opponent’s

After the FBI searched former President Donald Trump’s home, U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene expressed outrage to the hundreds of thousands of people who follow her on social media.

“They are trying to STOP President Trump from running in 2024,” she wrote on the messaging app Telegram. “And the Democrats are expecting you NOT to stand with President Trump!”

The note linked to Greene’s page on the fundraising platform Anedot, where supporters were encouraged to “emergency donate” to her campaign. On a separate fundraising site used by Republicans, WinRed, Greene added new merchandise to her online store: T-shirts and hats with the phrase “Defund the FBI.”

Not to be outdone, her Democratic opponent soon responded with his own fundraising plea. On Twitter, he posted multiple messages blasting her criticism of the FBI and asking supporters to donate to unseat her.

“Marjorie Taylor Greene wants to defund the FBI,” Marcus Flowers wrote on Sept. 1, including a link to his fundraising page. “This November, we’re going to make sure she’s out of Congress.”

It’s been like that for months: a cycle of over-the-top statements and fundraising pleas by Greene, a conservative firebrand, followed by Flowers asking for money to oust her after repeating what the Republican said.

How the AJC covers politics and elections

Providing Georgians with the information they need to participate fully in democracy is our highest goal. AJC reporters strive for fairness and accuracy. They do not support political parties and are not allowed to endorse, contribute to or campaign for candidates or political causes.

Reporters and editors are members of the communities they live in and are encouraged to vote, but they work to be aware of their own views and preferences and carry out their jobs in an independent, non-partisan way. As we scrutinize public officials and issues, we hold each other accountable for doing so from a position of independence.

We work hard to be evenhanded and fair, and we invite you to let us know how we’re doing.

It has paid off for both, landing them in the top 10 of all candidates for Congress nationwide. Flowers raised $10.7 million through June, even though Greene’s 14th Congressional District is considered safe for Republicans and historically receives scant national attention. Greene, a first-term congresswoman, had raked in $10.2 million.

Most of the money has come from outside of Georgia, and much of it has gone to raise still more money.

“My old boss, (former Congressman) John Barrow, used to say trains run on coal and campaigns run on gold,” said Chase Goodwin, Flowers’ campaign manager. “We are using every tool available to raise the resources needed to turn out every Democrat we can and persuade independents and Republicans to reject Marjorie Taylor Greene’s hate.”

He added that the money could also help other Democrats on the ballot running statewide in Georgia.

State Rep. Kasey Carpenter, a Dalton Republican, said the money flowing to this year’s contest far outpaces the actual competitiveness of the race, which Greene is heavily favored to win.

“It’s mind-blowing because it’s not necessary, it’s kind of a waste as far as political money goes,” he said. “But that just illustrates how polarizing she is. Either you love her or you hate her; there is no in between. The lovers are sending her money, and the haters are sending the other guy money.”

Arthur Rouse, a retired media producer based in Lexington, Kentucky, is among Flowers’ many out-of-state donors. He said he first came across the effort to unseat Greene on social media and was attracted to Flowers’ background as a veteran and defense contractor. Rouse in March wrote a check for $5,800, the maximum allowed.

He said he didn’t research the details of the race and wasn’t aware that Flowers faces long odds in November, but that doesn’t mean he regrets his donation.

“Whether or not Marcus Flowers can win, I don’t really care,” he said. “I just want to express myself that I’m for any candidate in some of these districts who is going to oppose some of these way, way fringe Republicans.”

The race could easily end up with the two candidates collecting $25 million combined in a district where 69% of voters are Republicans and 31% are Democrats, according to Princeton University.

On the southern end of the state in southwest Georgia there is a competitive congressional race that Republicans have targeted in their effort to retake control of the U.S. House. There, Democratic incumbent Sanford Bishop had raised $1.9 million through June, about the same as the Republicans challenging him.

Greene and Flowers have lapped those candidates in a race far less likely to be competitive, and the money has been used in ways that have drawn criticism. Flowers pays himself a salary of roughly $5,000 a month — which the Federal Elections Commission has said is legal — and Greene spent more than $92,000 to purchase a Buick SUV that takes her to campaign stops.

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution review of Greene’s and Flowers’ campaign finance reports also shows that both candidates have spent heavily on digital ads and fundraising consultants with the purpose of raising more money, deflecting expenditures from direct contact with voters in the district.

The basis of a rivalry

Greene was already a lightning rod when she entered Congress in January 2021, known for spouting baseless conspiracy theories, some of them tied to the QAnon movement. She also had a long history of making antisemitic, anti-Muslim and racist statements in speeches and online videos targeted at conservative audiences.

In the district, however, she has worked to connect with voters, and many are ready to give her another term in office even if they disagree with some of her most problematic antics.

“She’s a rock star,” Carpenter said recently. “Folks like her. This district — it’s gotten longer and it’s changed a little bit with the lines being redrawn — but, for the most part, it’s a lot of people that like people to stand up and say what they’re thinking. And so that resonates with a huge swath of voters in this district.”

Greene was sworn into office just three days before the deadly Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol, when Trump supporters stormed the building, spurred by his false claims of voting fraud after he lost his reelection bid.

Although she publicly condemned the violence, she later accused the federal government of mistreating those charged with assaulting police or entering the Capitol. And she has spread conspiracy theories and misinformation about the riot, sometimes deflecting from the reality that it was carried out by Trump supporters.

Flowers, who has never held office, said he decided to run against Greene because of Jan. 6. He says he views her as a threat to democracy.

He rose to the top in a crowded Democratic primary largely because of his huge fundraising advantage.

Flowers now circles the district wearing his customary black cowboy hat and has become a rock star in his own right among Democrats with long lines of well-wishers hoping for selfies greeting him at the party’s recent state convention in Columbus.

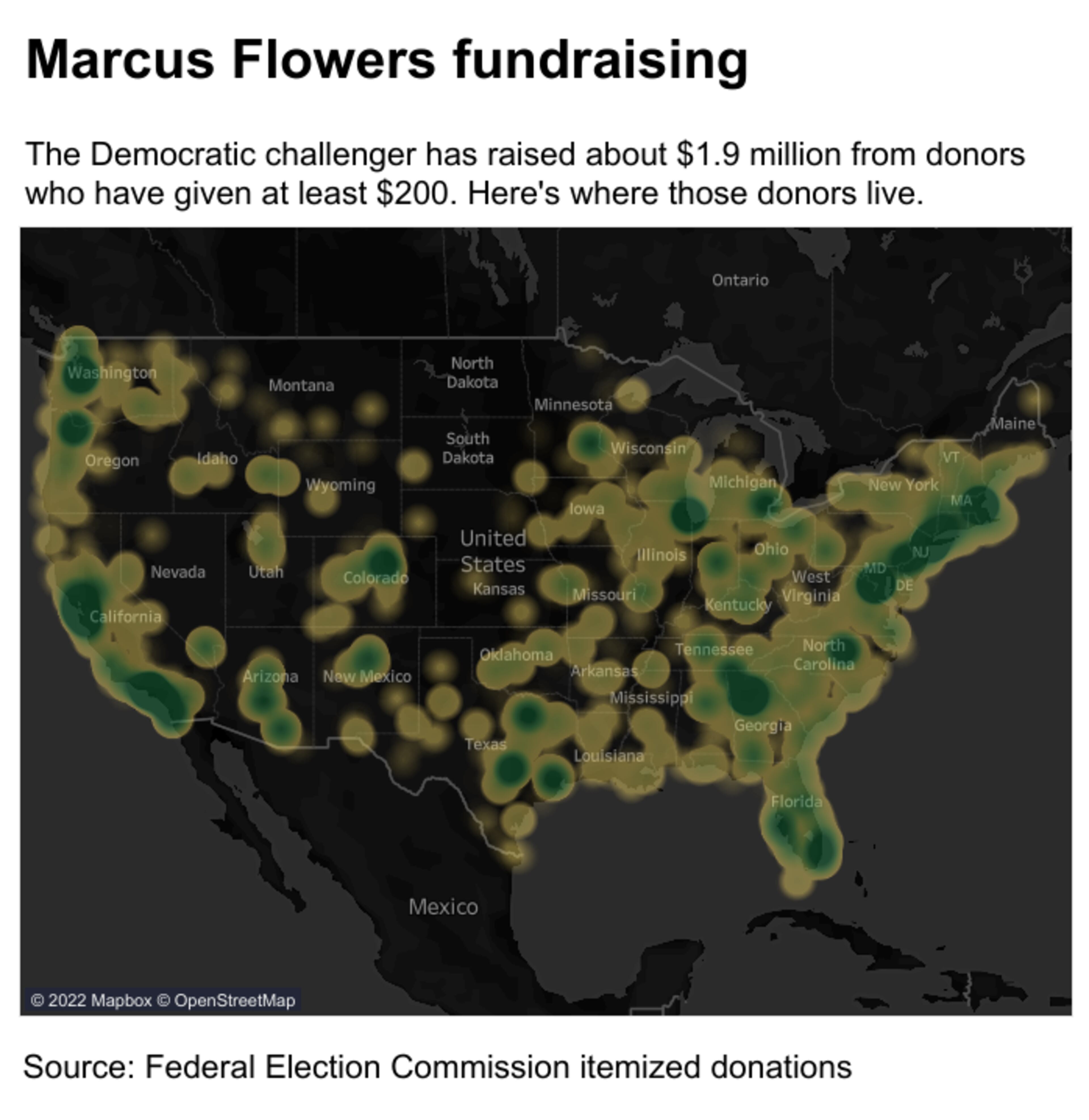

Because the race has been nationalized, both candidates are raising the vast majority of their money from outside the state. Most of the funds are coming from donors whose small contributions don’t reach the federal limit requiring full reporting of individual contributions.

Of the $4.7 million that has been itemized between the two, less than $100,000 comes from ZIP codes within the 14th District. Greene has received about $80,000 from inside the district, representing 3% of her itemized funds. For Flowers, the number is about $16,000, or less than 1% of all itemized dollars.

“Republicans from all over the country love Marjorie,” Greene’s campaign said in a statement. “This is reflective in her fundraising numbers, her followers and engagement on social media, and her demand in Republican primaries (candidates beg for her endorsement) just to name a few reasons.”

At the same time, her campaign mocks Flowers’ fundraising as squandered dollars in a heavily Republican district.

“Marcus Flowers’ consultants are fleecing Democrat donors, which is fine with Marjorie,” her team said. “This means $15 million-plus will go to Democrat wasted efforts instead of key swing districts and states. She is cheering him on.”

Spending money to make money

Both Greene and Flowers have spent millions of dollars on efforts tied to raising more money, according to a review of their expenditures.

Of the nearly $8 million Greene has spent through June, $5 million is categorized under “solicitation and fundraising expenses.” The second-largest category of spending is $2.4 million for “administrative/salary/overhead expenses.”

The vendor who has received the most money from Greene’s campaign is LGM Consulting Group, a digital fundraiser that required at least one previous candidate to pay as its fee 80% of the money the company brought in from new donors. The company, which first became active during the 2018 campaign cycle, currently ranks among the top 100 political vendors nationally.

LGM’s clients include U.S. Sens. Josh Hawley of Missouri and Rick Scott of Florida, as well as Georgia Republican Mike Collins, who is expected to easily win the 10th Congressional District contest in November. But the company has made the most money by far this cycle from Greene’s campaign: $1.1 million.

At least $3.5 million of the $10 million Flowers has spent falls under categories related to fundraising expenses. And nearly all of that has gone to one company, Blue Chip Strategies.

Bobby Kaple, a former TV news anchor and unsuccessful congressional candidate, and Michael Carcaise, a Colorado-based political consultant, started Blue Chip Strategies in 2019.

The company has been paid by a handful of other candidates in Georgia, including Democratic attorney general nominee Jen Jordan. Flowers’ campaign has been the most lucrative for Blue Chip, accounting for 91% of all its reported earnings, about $3.4 million.

A person familiar with Flowers’ campaign told the AJC that the money paid to the company includes funding for digital ads on Facebook and other platforms. The campaign and Blue Chip declined to share the details of their agreement, such as whether the company earns a percentage of any amount raised as its fee.

Kristin Oblander, a veteran fundraiser in Democratic circles in Georgia, said money raised by Flowers could be better spent on races where the Democratic nominee has a stronger chance of winning in November.

Oblander said that Greene tends to drum up emotions from left-leaning voters with her controversial statements.

“It excites the donors to think they are somehow harming her politically,” Oblander said, “but there are better vehicles to do this.”