When Calvin Smyre was in his early 20s, an academic setback caused him to take a look in the mirror — and he didn’t like what he saw.

His grades weren’t great, he wasn’t taking school seriously and he didn’t get to graduate with the rest of his class.

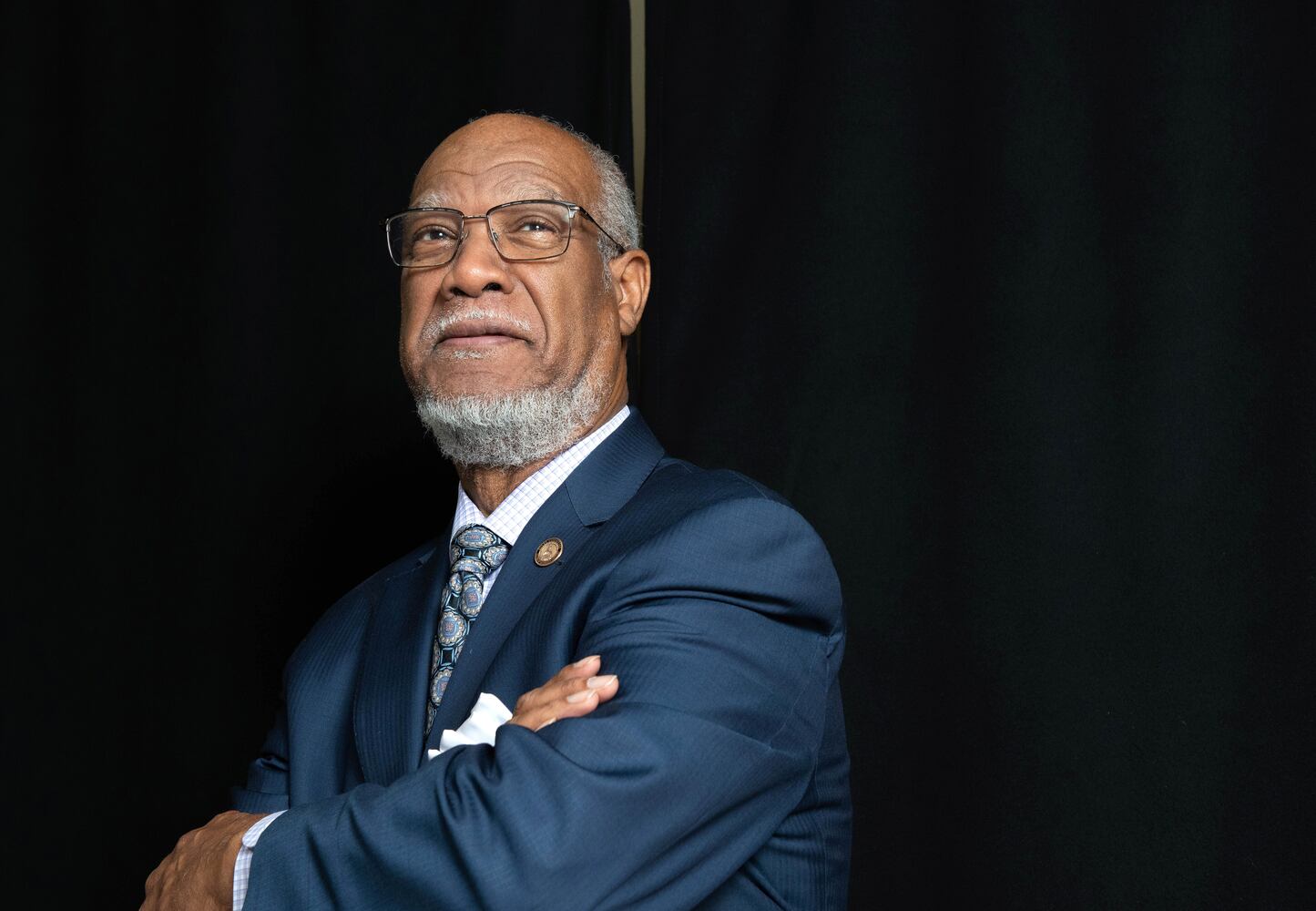

Now 74, the Columbus Democrat will hear the gavel fall for the last time in the Georgia House on Monday when he retires after a storied 48 years in office. He will walk out proud of the man he’s become.

And while his plan was to make it to a nice, round 50 years, President Joe Biden sped up Smyre’s retirement plans last fall when he nominated the legislator to serve as the U.S. ambassador to the Dominican Republic.

Soft-spoken and humble, Smyre quotes his friend the late Gov. Zell Miller when he reflects on how far he’s come in his life.

“If you ever see a turtle on a fence post, you know he or she didn’t get there by themselves, somebody had to put them there,” he said. “That’s where I am in my career. I didn’t get here alone.”

Bennie Newroth, who was Smyre’s first campaign manager and worked on every one of his races, said she couldn’t be more proud that a son of Columbus was in line to represent the United States abroad.

“I think he has grown from not just a politician, but a statesman, and I think there’s a difference. And it’s been an honor to watch that evolution,” Newroth said.

Smyre has experienced many firsts in his career. He was the first lawmaker to represent his Columbus district, which was newly drawn in 1974. He was the first Black legislator to serve as a governor’s floor leader in the House when Joe Frank Harris picked him for the job. And he was the first Black person to lead the Democratic Party of Georgia.

Georgia political historians say Smyre has served more consecutive years in office than any other lawmaker.

Gov. Brian Kemp called Smyre an unmatched statesman who’s worked to make Georgia a better place. Smyre is connected to the Kemp family in two ways — he served with Kemp in the General Assembly and also with first lady Marty Kemp’s father, state Rep. Bob Argo.

“Calvin’s passion for public service and his love for the Columbus community and our state will be missed at the Georgia state Capitol, but we know he will bring that same spirit of dedication and leadership in service to our nation,” Kemp said.

‘The guy in the glass’

Smyre was born at Fort Benning, the son of a U.S. Army officer father and homemaker mother, and he moved from base to base. He spent the bulk of his high school years in Germany before returning to Georgia to attend Fort Valley State College.

Shedding a clean-cut demeanor, Smyre cut loose in college, becoming known as a crafty card player and indifferent student who joined Omega Psi Phi Fraternity Inc. — whose members have a reputation for being boisterous and wild. He graduated a semester later than he was supposed to, something that still bothers Smyre.

“I was not focused,” he said. “I was not doing what I should have been doing.”

Smyre also got married while he was in college and divorced in 1970. He never remarried. His daughter, Theresa, died in December at age 55.

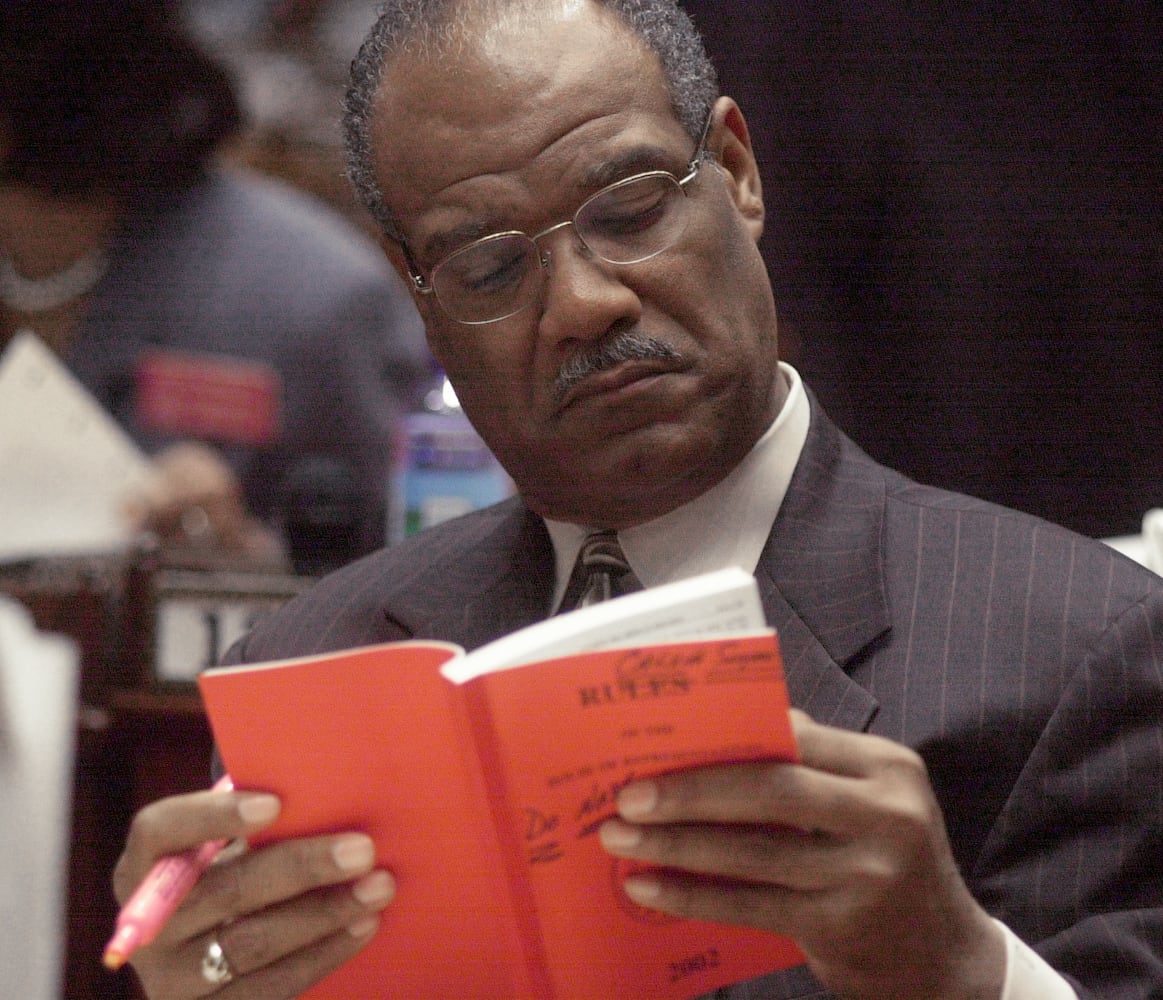

Around the time he graduated, he first read the poem “The Guy in the Glass” by Dale Wimbrow. Smyre said it changed his life.

He can still recite it from memory.

“You can fool the whole world down the pathway of years, and get pats on the back as you pass, but your final reward will be heartaches and tears if you’ve cheated the guy in the glass.”

Smyre said, “I said then, in December 1970, I would never cheat myself again.”

More than five decades after graduating, he serves as the chairman of the board of the Fort Valley State University Foundation.

After a few post-college jobs, including working as a substitute teacher, Smyre joined what would become Synovus as a bank manager and eventually became executive vice president of corporate external affairs and president of the Synovus Foundation before retiring.

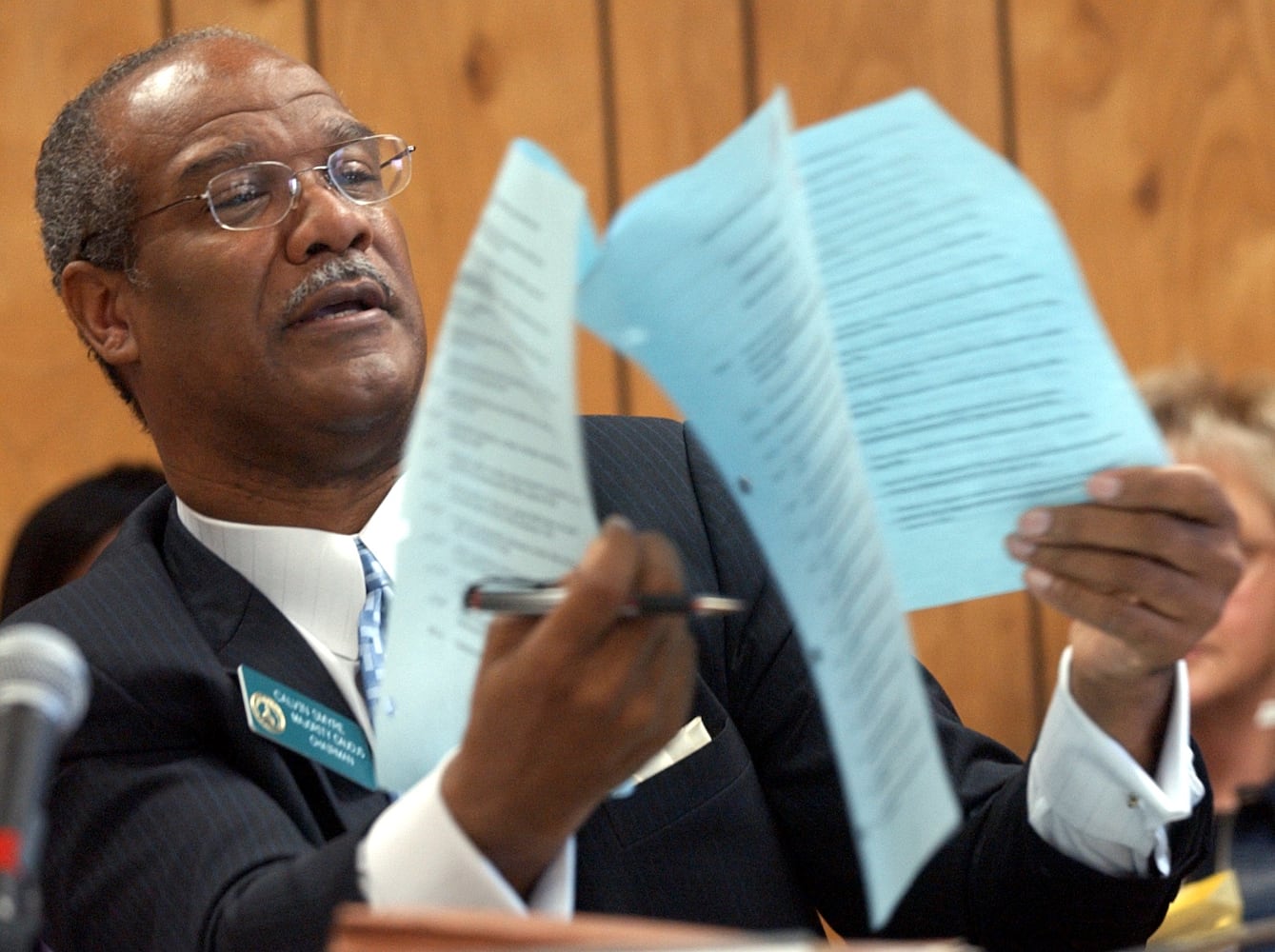

The negotiator

Elected at 26 years old, becoming the youngest lawmaker in Georgia at the time, Smyre quickly rose up the ranks from freshman lawmaker to Harris’ floor leader in 12 years.

A 1988 profile of Smyre in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution included quotes from colleagues who questioned his ability as the state’s first Black floor leader to lead on issues of race.

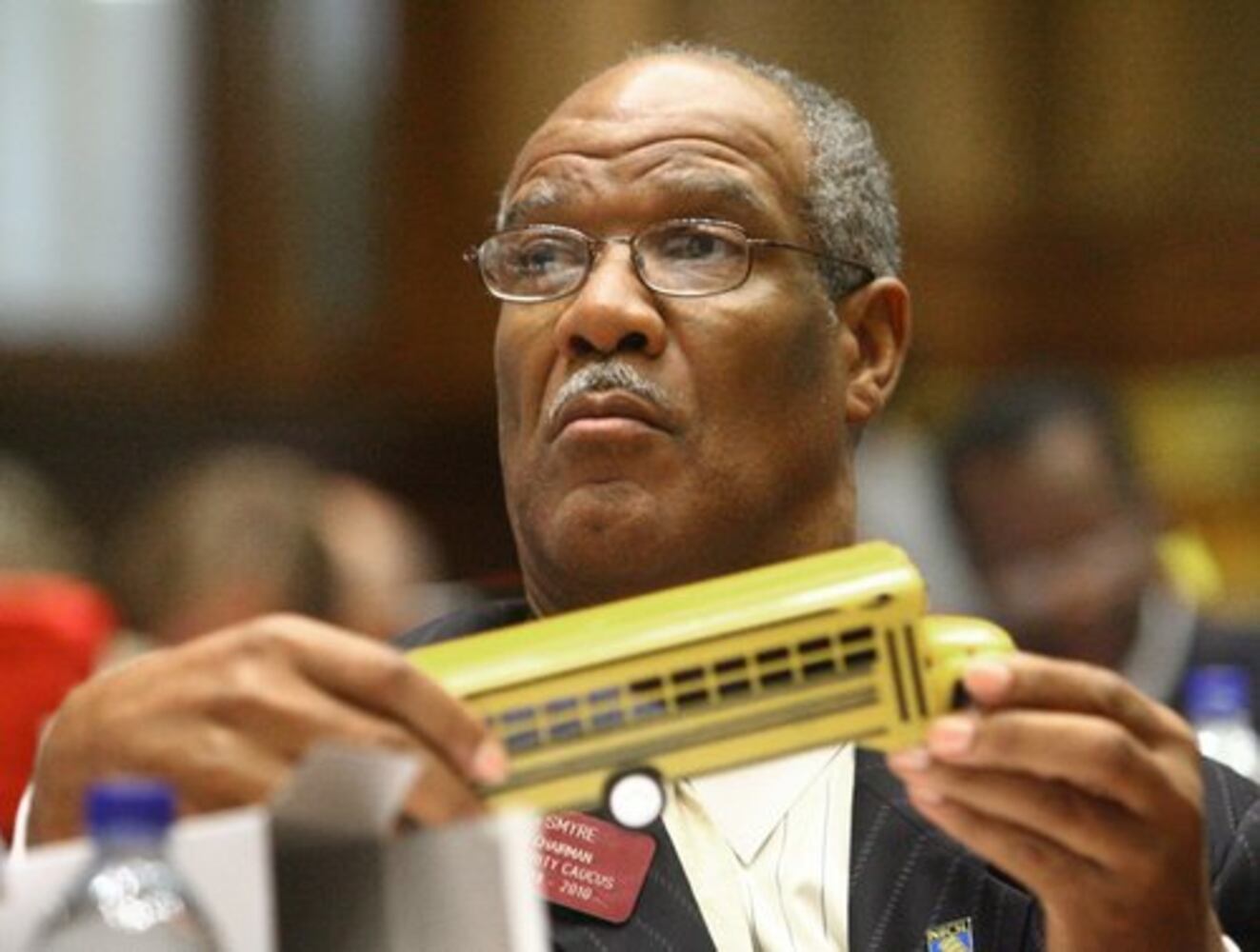

In 1987, his first year as Harris’ floor leader, Smyre opted not to push lawmakers to change the state flag to get rid of its Confederate battle emblem, to the ire of some of his Black colleagues. But by 2001 he worked with Gov. Roy Barnes to make it happen.

“It’s tough to tell governors, sometimes, things they don’t want to hear,” Barnes said in an interview. “When we got down to changing the flag, Calvin is one that came to me. He says, ‘You know, we’ve got to do this.’ And to be quite frank with you, it was not on my agenda to do.”

Smyre has been in the room for the negotiations that led to many of the state’s major advancements over the past 50 years: enacting the HOPE scholarship, building the Georgia Dome, establishing the Martin Luther King Jr. state holiday, placing King’s statue on the state Capitol’s grounds and — most recently — overhauling the state’s citizen’s arrest statute and passing a hate-crimes law.

“If Calvin supported it, it was OK,” Harris said.

Relationships matter

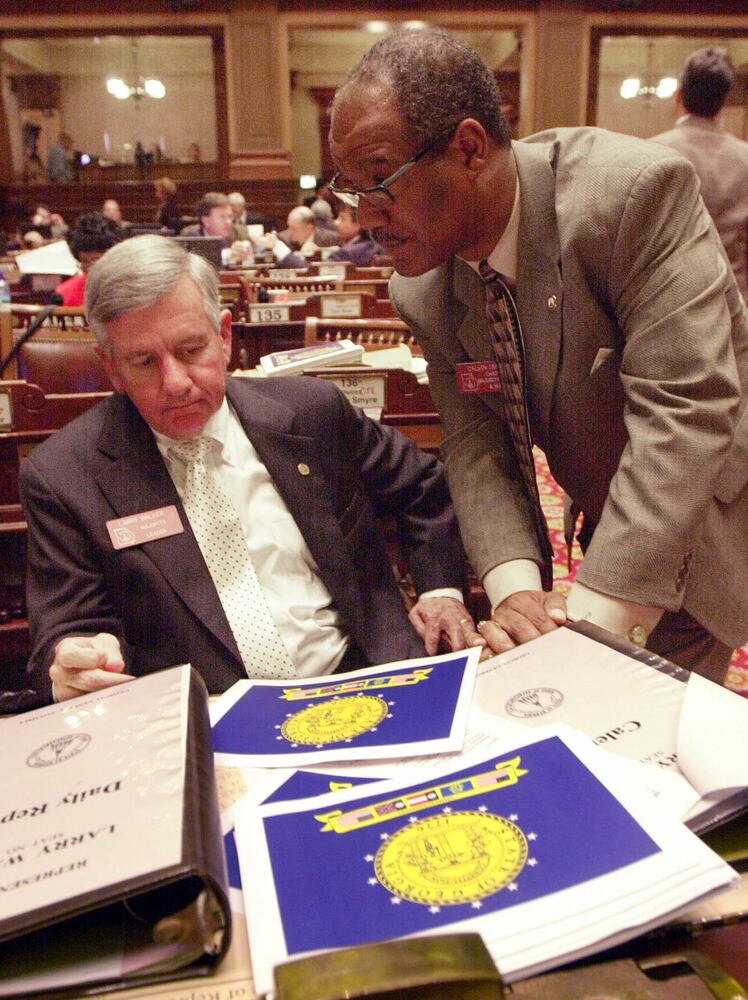

Smyre’s ability to work across the aisle has endeared him to most, if not all, of those he’s worked with over the years.

He’s been able to count as friends both national politicians — such as former President Bill Clinton; his wife, former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton; and former Vice President Al Gore — and Georgia politicians, including the late House Speaker Tom Murphy, a Democrat, and Republican House Speaker David Ralston..

“I often tell him, I said, ‘I know that there was a speaker here that’s worked with you longer than me, but there’s not been a speaker that’s loved you as much or relied on you as much as I have,” Ralston said in an interview with GPB.

Smyre’s fraternity brother Thomas Dortch said the fact that the Columbus Democrat isn’t overly partisan has helped his political career.

“He understands that to get things done, you’ve got to reach across the aisle,” Dortch said.

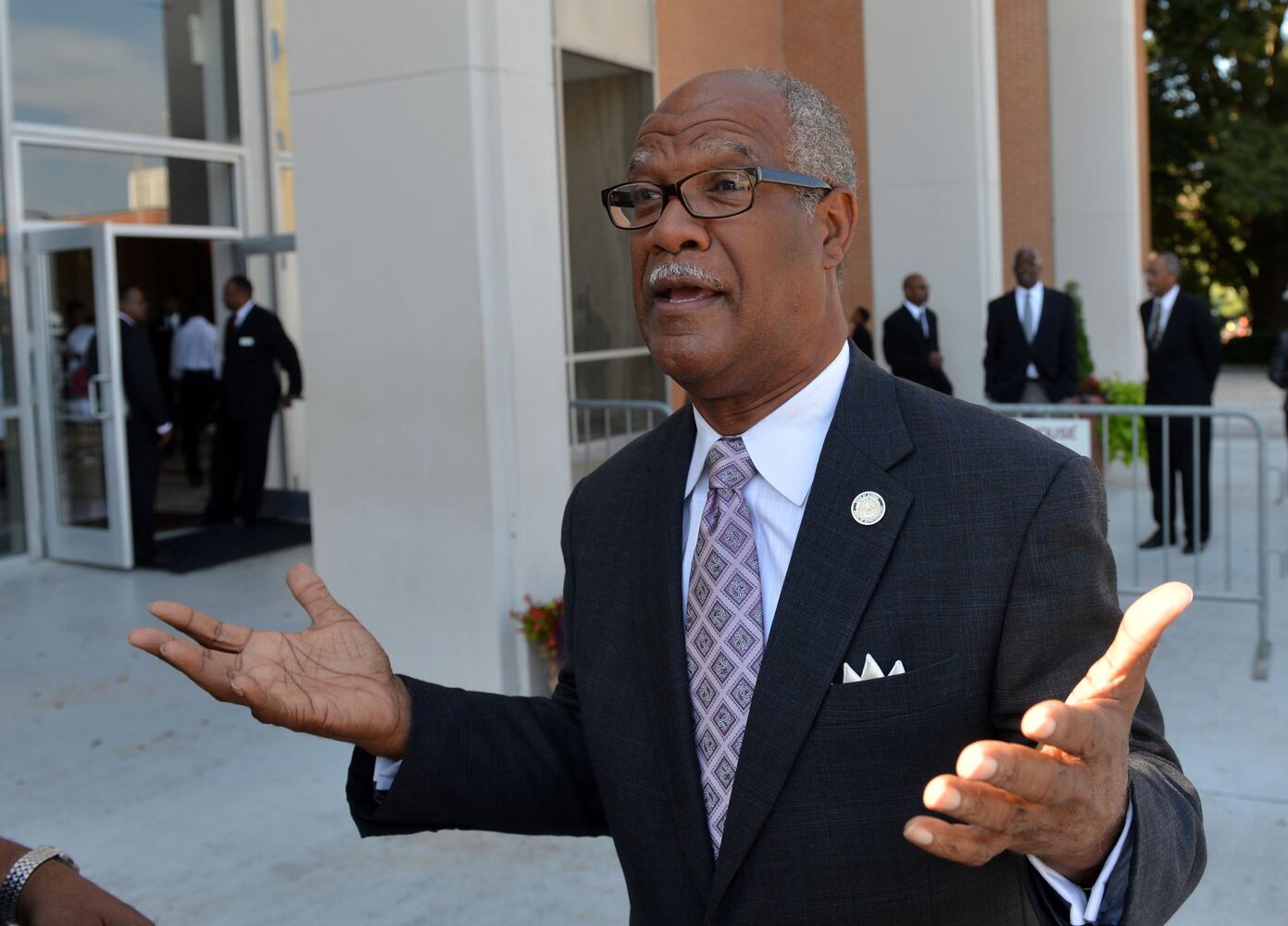

Knowing when it’s time

Smyre often marvels at the ways the Legislature has changed in his 48 years in office. In 1975, the House was made up of 159 Democrats and 21 Republicans. Nineteen of the representatives were Black. Eight were women.

Today, there are 76 Democratic representatives and 103 Republicans. One seat is vacant. There are 63 women serving in the state House. At least 49 members are Black, three are Asian American and two are Hispanic.

“I see myself reflecting back on 1975,” he said, “and it’s time for me to do what others did for me and pull somebody else up by the bootstraps.”

Gov. Nathan Deal called Smyre’s nomination well-earned. The two served together in the Legislature, and they worked together on the King statue.

“He’s put in his time, he’s paid his dues, as the old cliché goes, and it’s always nice to see somebody rewarded based on merit,” Deal said.

Smyre said it will be difficult to leave the Legislature, Columbus and Georgia, but especially his grandchildren, who are 22 and 23, so soon after their mother’s death.

But life is about doing the work for the ones you leave behind, Smyre said.

“My motto and my mantra has been always to plant seeds to trees for the shade you may never see,” he said. “If you think of it in those terms, you’re not thinking for the moment, you think for the future.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured