SAVANNAH — The simple street signs sprinkled along the edges of this city’s downtown state the obvious: Passersby are entering a National Historic Landmark District.

Savannah’s historic district is often compared to a time capsule, with homes and buildings dating to the 1700s and an urban design plan famous the world over for its uniform street grid broken up by a series of charming tree-covered squares.

City of Savannah officials have taken the initial step in having some of those district boundary markers moved, requesting a change to expand the borders to include the entirety of Forsyth Park. A bigger district is part of a broader update to the National Historic Landmark documentation that city leaders are seeking from the National Park Service.

The update would be the first since 1977, when Savannah leaders submitted documentation to codify downtown’s National Historic Landmark status first granted in 1966. The city contacted NPS officials late last year about revising the National Historic Landmark paperwork, and city staff began the process earlier this month.

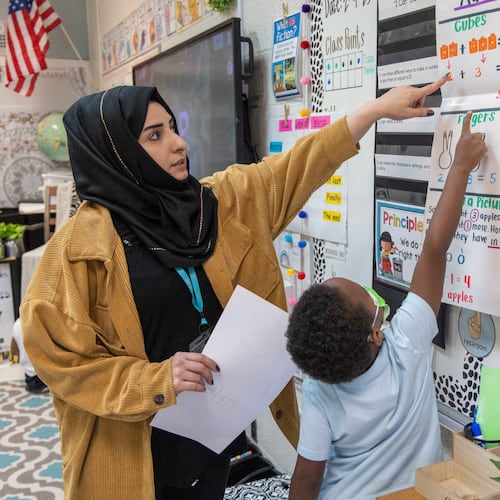

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

City Manager Jay Melder told Savannah’s WTOC TV last week that the update will better reflect efforts made in recent decades to protect the historic nature of the district.

“We are a unique city with a unique historic district that is the jewel of Georgia and a national treasure,” he said.

Development within the historic district has been a subject of consternation for much of the past two decades, dating to when downtown became an international tourism destination. Hotels have proliferated in the 1-square-mile landmark district since the end of the Great Recession, with 57 inns and hotels now operating within the existing boundaries and at least five more lodging establishments in the planning or development stages.

The pace of development prompted a 2018 review of the district’s historic integrity. The study, performed by a third-party consulting firm, noted several instances of historic erosion, much of it related to deviations from the urban plan employed by Savannah’s founder, Gen. James Oglethorpe, in laying out the original city.

The study resulted in the NPS classifying Savannah as “threatened” in the agency’s National Historic Landmark monitoring program. The designation was meant to denote that the district had suffered or was in imminent danger of a severe loss of integrity. However, the NPS made clear in its report that Savannah was not in danger of losing its status.

Even so, city officials and business leaders have implemented many refinements to historic district development standards in the six years since. In one instance, the City Council demanded changes to a mixed-use development project that would have eliminated a lane that was built as part of the Oglethorpe Plan. In another, hoteliers and other hospitality industry leaders worked with city staff and downtown residents to restrict development of lodging in heavily residential areas of the historic district.

A letter the NPS sent last month to the city acknowledged the work done to address the 2018 concerns.

“We believe your proposal is in keeping with the National Park Service’s (NPS) 2018 recommendation regarding preservation practices to facilitate management and improve the overall health of the National Historic Landmark District,” the letter states.

Credit: Blake Guthrie

Credit: Blake Guthrie

The letter also noted the agency has suspended its National Historic Landmark monitoring program and that none of the nation’s historic districts, including Savannah, are currently designated as “threatened.”

The city’s proposed update would stretch Savannah’s historic period from its 1733 founding all the way to the 1970s. Doing so would expand the parameters for future reviews of the district’s historic integrity, such as the one done in 2018, beyond adherence to the Oglethorpe Plan.

Savannah’s historic preservation movement started in 1955 when a group of seven women raised money to save the Davenport House, a brick mansion built in 1820, from demolition. Those activists formed the Historic Savannah Foundation, which still operates today.

The foundation’s current leader, Susan Adler, applauded the city’s decision to pursue a National Historic Landmark update.

“We are encouraged by this latest development from the National Park Service and will continue to work closely with the City of Savannah to protect Savannah’s National Historic Landmark District,” Adler said in a statement. “For the past 69 years, Historic Savannah Foundation has worked diligently to save the buildings, places and stories that define our past as well as our future.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured