Jan. 6 defendants wait for Trump pardons

Phillip “Bunky” Crawford stood in the kitchen of his spacious Bremen home, Christmas music playing in the background as he reflected on the past four years of his tumultuous life.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Crawford shoved his way through the crowd at the U.S. Capitol to the very front of the teeming crowd clogging the entry to a tunnel on the Lower West Terrace, pushing and swinging at police amid the mass of rioters and police officers fighting in an entrance tunnel to the Senate wing.

More than two years later, Crawford was arrested and charged with 11 felony and misdemeanor charges. He eventually pleaded guilty to six charges, including civil disorder and three counts of assaulting police, all felonies. Following a trial in June of last year, he was found guilty of another count of assault and four misdemeanors.

His sentencing is set for later this month where he faces a possible prison term that could take him away from his wife and three children for years. That’s what makes what he said up front a stunning commentary on the fourth anniversary of the riot.

“If I had to go back, I would do it all the same,” he said.

Crawford, 50, is one of 44 people with Georgia ties charged in the U.S. Capitol riot. Many defendants have expressed their regret for their actions, but Crawford never has.

All of the Jan. 6 cases are handled through the U.S. District Court in Washington, a high-profile federal court where judges are required to address some of the most difficult political questions in both a criminal and civil context.

In dozens of briefs filed with the court, many Jan. 6 defendants have said they were merely caught up in the emotions of the day and regret their behavior. Others said they were misled into thinking Donald Trump had ordered them to the Capitol to stop the transfer of power from him to incoming President Joe Biden.

One Georgia man blamed his behavior on copious consumption of alcohol and drugs on the day of the riot, while others pointed to traumatic childhoods as mitigating factors for their lapses in judgment.

“There is a good percentage of these people who do feel some sort of genuine remorse and realize that what they did was a mistake,” said Luke Baumgartner, a research fellow at George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. “A lot of those people are the ‘normies’ who got caught up in the echo chamber and genuinely believed the election was stolen and got caught up in the crowd.”

That does not describe Crawford, who blames his federal public defenders for pushing him to take a plea.

“But see, the thing is, no lawyer wants to fight the federal government on this Jan. 6 (investigation),” he said. “If you find one, it’s going to cost you half a million dollars. Really, and that’s the truth.”

Crawford has a new court-appointed lawyer now. In November, that lawyer tried to get Crawford’s sentencing delayed, saying his client wants to withdraw his guilty plea. The prosecutors in the case opposed the delay, pointing out that defendants cannot withdraw their pleas on a whim and Crawford has not laid the proper legal groundwork necessary to delay his sentencing.

Judge James E. Boasberg, chief judge of the U.S. District Court in Washington, sided with prosecutors, although he said he would reconsider if Crawford came up with “a viable claim” for changing his plea.

With time running out, Crawford is counting on President-elect Trump to deliver on his promise to pardon him and the nearly 1,600 people charged in the U.S. Department of Justice’s sweeping investigation.

Crawford’s laptop is filled with video images. Surveillance footage and police body cameras show him in the thick of the fight. In his mind, he was justified. Since his arrest, he has maintained that the sole reason he shoved his way to the front line in a battle with police was to protect Victoria White.

White of Rochester, Minnesota, is something of a folk hero among supporters of Jan. 6 defendants who say she is a victim of police misconduct during the unrest.

Videos and photos circulated across the internet show White at the front of the melee, her face bloodied after being struck by a police baton. During the struggle, White claims she was hit by a baton and fists dozens of times before being dragged by police through the cordon and into the Capitol.

In August 2023, just a few weeks after Crawford’s arrest, White agreed to plead guilty to participating in civil disorder by obstructing police, a felony that carries a maximum penalty of five years in prison. White’s lawyers argued that White’s behavior was not as severe as others who fought with police and pointed out she was struck by an officer with a metal baton, “opening a wound and causing her to bleed profusely.” In a brief filed before her sentencing, her lawyers acknowledged White tried to push past police to get into the Capitol and that she “deeply regrets her conduct.”

White was sentenced to eight days in prison, served over four weekends, followed by three months of house arrest and two years of probation, plus a $2,000 fine.

White is suing two of the Capitol Police officers she claims “repeatedly and mercilessly” beat her. In the suit, she claims she was pushed into the tunnel by the crowd. A fierce Trump supporter who lead a “stop the steal” protest in her hometown before going to the Capitol, White has claimed she was not part of the violence of the day and is seeking $2 million in damages.

In October, a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit but left open the possibility that White could refile with new claims.

An unfinished investigation

The Justice Department’s investigation is nowhere near complete. Almost a third of the nearly 1,600 people have yet to enter into a plea agreement or stand trial on their charges, and multiple new defendants are arrested and charged every month.

Because so many defendants took pictures or made recordings of their actions during the riot and posted them on social media, charges brought against them have been very hard to beat. Only three defendants have been acquitted of their charges and another dozen have had their cases dismissed.

Many of Trump’s admirers have criticized the investigation, joining the president-elect in calling the defendants “patriots” and “heroes.” Others not aligned with Trump have been critical of the courts for handing down sentences they see as too lenient. About two-thirds of defendants have been sentenced to time in prison, with the median sentence running 240 days, or about eight months, according to a database maintained by NPR.

Lately, the investigation has run into some trouble.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court tossed out charges of obstruction of an official proceeding against Jan. 6 defendant Joseph Fischer, a former police officer from Pennsylvania. The Justice Department had charged more than 250 other defendants with the felony charge. The 6-3 decision, which broke along the court’s partisan divide, tossed into doubt many convictions, including those of some Georgia defendants.

William McCall Calhoun, an Americus attorney, who was among the first wave of rioters to enter the Capitol, was released from prison within days of the Fischer decision on order of the federal appeals court in the D.C. circuit, which vacated his felony conviction. The release came just about six weeks before his projected release. The Georgia Supreme Court suspended his license after his felony conviction, but with the felony off his record, Calhoun could ask to be reinstated.

Pardons loom

Setting aside the Fischer decision, the hundreds of convictions and guilty pleas could be undone should Trump follow through on his campaign promise to pardon the rioters.

In an interview last month with NBC’s “Meet the Press,” Trump said he would pardon the rioters on his first day in office, claiming defendants were forced to plead guilty in “a very corrupt system.” But he left himself some wiggle room, saying there “may be some exceptions.”

The promise of pardons hovers over the Jan. 6 prosecutions. In December, a New York defendant sentenced to a year in prison shouted at the judge, “Trump’s gonna pardon me anyways.”

U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth was unmoved.

“I will do my job as I’m bound by oath to do, and the president will do his. It’s as simple as that,” he said at the sentencing.

Dominic Box, a conspiracy theorist from Savannah who livestreamed his way through the Capitol on Facebook, is counting on a pardon.

“I am expecting a pardon and believe every J6er deserves a pardon, whether they were violent or nonviolent,” Box told a reporter for USA Today in an interview from the Washington jail.

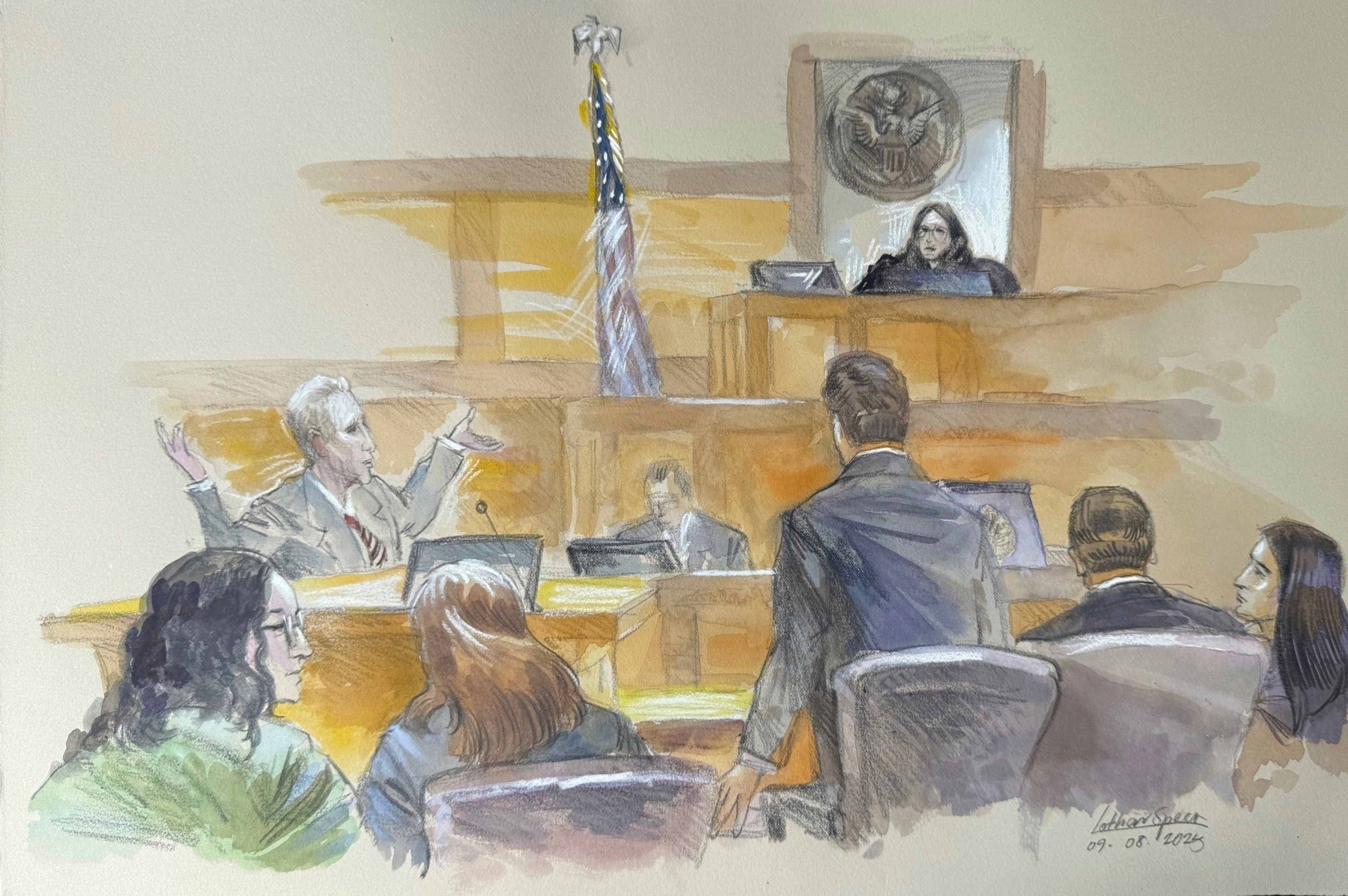

Following a June trial, U.S. District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly found Box guilty of two counts of felony civil disorder and four misdemeanors. His sentencing is scheduled for February.

Baumgartner said the possibility of presidential pardons does not seem to have slowed the Jan. 6 investigation.

“In my opinion it kind of looks like the government is still going after these people,” he said. “Whether or not they continue to after Inauguration Day remains to be seen.”

Baumgartner said many in Congress are being quiet on the subject as they await Trump’s return, but people who were in Washington that day haven’t forgotten.

“If you talk to any number of people who lived here on Jan. 6, it is still fresh in their mind,” he said. “The entire city shut down. When does any capital of any country shut down?”

‘I’ve lost everything’

In the kitchen of his Bremen home, Crawford flipped through a box of old photos and laminated newspaper clippings from his days as a star fullback on the Pebblebrook High School varsity squad. One yellowing clip shows Crawford plowing through a defensive line.

“I led the state in rushing in 1994 as a fullback, up until my last game, but … ,” he said, trailing off. “I played football a long time. I’ve had a lot of concussions.”

With his squat frame and thick muscular arms, the 50 year old looks as if he could still play.

The photographs spilled out across the kitchen counter. “Yeah, there’s my wedding, and a lot of Christmases,” he said. “My daddy always tried to provide. We’d go to vacation every year to the same place.” Daytona Beach, Florida, he said.

The son of a Baptist preacher, Crawford described his upbringing as strict but warm. After high school, Crawford went to Georgia Military College for a year before transferring to Mercer University for football, but he didn’t graduate. He tried the Army for a bit, before leaving with a medical discharge. After that, it was driving trucks and a couple of seasons with the semipro West Georgia Renegades football team before settling down, getting married and raising a family.

Over the last decade, Crawford gradually became interested in politics and concerned about the direction of the country. Perhaps ironically, he spoke about how important he believes it is for people to submit to government authority and said he was upset at the “evil” he saw in the social justice protest movements of the spring and summer of 2020.

“The media supported these — the left, you know? And I know you may disagree with this, but I’m going to tell you how I see it, OK?” he said.

Crawford ticked off a list of grievances, including calls to defund the police and cities that declared themselves “sanctuaries” for the protection of immigrants. It all built up to the 2020 election, he said.

“It was like a well-orchestrated brainwashing of trying to get people against the police or something,” he said.

By comparison, Crawford said most of the pro-Trump crowd on Jan. 6 was not opposing the police, despite “crazy amounts” of excessive force by officers. But his memory of the day doesn’t match the hours of video showing rioters pushing past police lines or fighting with officers who attempted to stop them.

More than a third of Jan. 6 defendants are charged with assaulting or resisting police, including 171 defendants charged with using a deadly or dangerous weapon or causing serious bodily injury to police during the riot.

The Justice Department claims 140 police officers were assaulted that day and rioters caused more than $2.8 million in damage to the Capitol. Typically, evidence for those charges comes from surveillance video, videos shot by rioters or journalists, and police bodycam footage.

Crawford doesn’t believe the mainstream accounts of the riot. In a wide-ranging conversation, he resurfaced a number of conspiracy theories about the day that take responsibility for the violence off the pro-Trump crowd and place it on police, the FBI, Democrats and leftist activists.

He said he is counting on Trump to come through with his promise of pardons, but he said that’s not enough. Personally, his business and savings are gone and his credit is ruined.

“I’ve lost everything. I’ve sold everything I’ve got and nothing is ever going to be done about it,” he said.

Crawford said that, while he is “all about healing and forgiveness,” Trump will need to do more than just pardon the defendants. The incoming president needs to go after “these people that love their jobs more than their country,” he said. That includes members of the congressional committee that investigated the riot, he said.

In interviews, Trump has said committee members should be jailed.

“Heads are going to roll,” Crawford said.

He just hopes the president-elect doesn’t forget him and the other defendants as he enacts his revenge.