Hurricane Helene is a test for Georgia’s governor and state leaders

The deadly storm that raked Georgia with hurricane-force winds and triggered catastrophic flooding will test Gov. Brian Kemp like no other natural disaster that’s hit the state in decades.

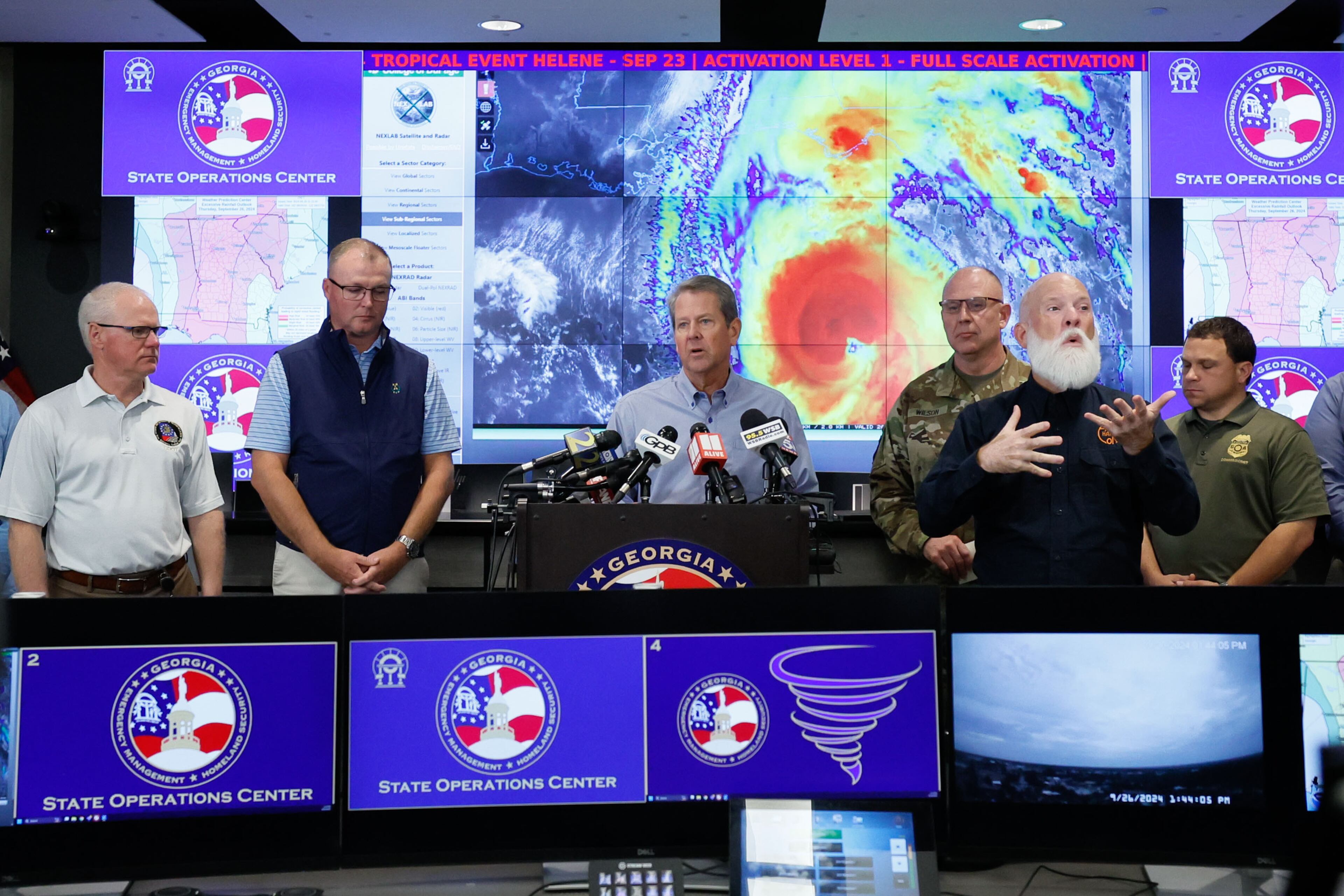

Kemp has taken a firm hand on the state’s response to Helene, which barreled through South Georgia early Friday as a Category 2 hurricane before being downgraded to a tropical storm. It left at least 15 Georgians dead by the time it swept into North Carolina and Tennessee.

The governor blanketed the airwaves to urge Georgians to stay off the roads, issued a state of emergency order long before the behemoth storm whipped Florida’s coast and authorized as many as 1,500 Georgia National Guard troops to assist with the cleanup.

But Helene’s size presented an unprecedented challenge for Kemp and his administration, with a 400-mile wind field stretching from Columbus to Savannah that the governor said makes it a truly “statewide event.”

So, too, will the cleanup of one of the deadliest disasters in the state in decades. Not since Alberto dumped more than 2 feet of rain on the state in 1994, killing more than 30 Georgians, has a tropical storm or hurricane claimed as many lives in Georgia.

For Kemp, the next days and weeks could help define his second term. With potential higher aspirations after his term ends in 2027 — his allies say a White House bid isn’t out of the question — how the governor handles the aftermath will be under the microscope.

“It sounds crass, but the fact is that politicians are judged by how they perform in moments of crisis,” said Brian Robinson, a veteran strategist who was a senior aide to Republican Nathan Deal when he was governor.

“There’s lots of upside and downside for Kemp. But we’re already in recovery mode, and he’s everywhere,” Robinson said. “He’s made himself the face of the response.”

The governor said in an interview that his focus is on both the immediate impact and long-term effects of the storm. He’s particularly concerned about the toll Helene exacted on the vast expanse of farmland in its trail of destruction.

For farmers already struggling with drought and higher prices, Kemp told the “Politically Georgia” podcast, it’s the “worst time” for a storm with such far-reaching consequences for the state’s largest industry.

“This storm is going to be such a hard hit financially. It will take us a long time to even get a number,” Kemp said, adding: “Everyone knows it’s going to be historic in a lot of ways.”

‘Be seen’

Some are already pointing to Kemp’s response to Hurricane Michael, which ravaged South Georgia in October 2018. The storm was so destructive, uprooting crops on its path of misery, that the World Meteorological Organization retired Michael’s name.

Kemp wasn’t governor when Michael hit — he was locked in a tight election battle for Georgia’s top office at the time. But in his first year in the governor’s office, he dealt with the storm’s aftermath: a grueling fight in Congress for disaster relief that put him at odds with fellow Republicans. It took nearly a year of legislative wrangling to clear the way for the aid and longer still for it to trickle down to farmers.

Often frustrated by the gridlock, Kemp privately badgered then-President Donald Trump for the promised funds, then used his bully pulpit to bemoan the “rotten core of some in Congress” who initially refused to broker a compromise for the funding.

With more recent natural disasters, Kemp and his agency heads have stuck to a better-safe-than-sorry mantra.

His administration regularly issues emergency orders long before storms strike, and he’s encouraged businesses and schools to close ahead of the most menacing ones. Storms are preceded by frequent news conferences, and they’re often followed by detailed tours of disaster sites.

“People don’t expect to see your congressman or senator during a storm. But everyone expects to see your governor,” said Cody Hall, Kemp’s longtime deputy.

“And Gov. Kemp’s approach is to be seen.,” Hall said. “To make sure that he has enough information to help coordinate the state’s response, but also let the experts do what the experts do.”

No one in Georgia government wants a reprise of the disastrous state and local response to icy gridlock a decade ago that turned metro Atlanta into a laughingstock and transformed how leaders prepare for major weather events.

Back then, the state’s emergency chief apologized for failing to awaken Deal, then the governor, as national forecasters updated winter warnings and urged drivers to stay off the road. And he took the blame for waiting until hours after the gridlock seized metro Atlanta’s streets to open a command center to respond to the mess.

The lackluster political response ushered in vast changes to Georgia’s emergency management protocol — and vows from Deal and local officials for more aggressive and preemptive action. That strategy is still intact.

More recently, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens took heat for what critics panned as a delayed response during a dayslong water main leak that left thousands without drinking water. Dickens called the mess a “wake-up call” to be more aggressive about monitoring aging infrastructure.

“We have to get prepared anyway, for whatever may come,” Dickens said Wednesday at one of his flurry of news conferences as Helene churned toward Georgia. “So we prepare for the worst, hope for the best.”

Robinson, Deal’s former deputy, pointed to a different natural disaster as a North Star for state leaders: then-Gov. Zell Miller’s hands-on reaction to Alberto three decades ago.

It came as the Democrat was locked in a tough reelection battle against a GOP challenger, and his all-out approach helped secure a second term after a surprisingly close call.

The weeks ahead for Kemp could hold a different significance.

“If Brian Kemp has national aspirations, this is a moment for him to grab the national stage, look in command, look empathetic and show how capable he is,” Robinson said. “And if he can pull that off, it’s going to enhance his image far beyond the borders of Georgia.”

Atlanta City Hall reporter Riley Bunch contributed to this article.